Materials required: iPad or language app, logbook, projector, whiteboard, Internet connection

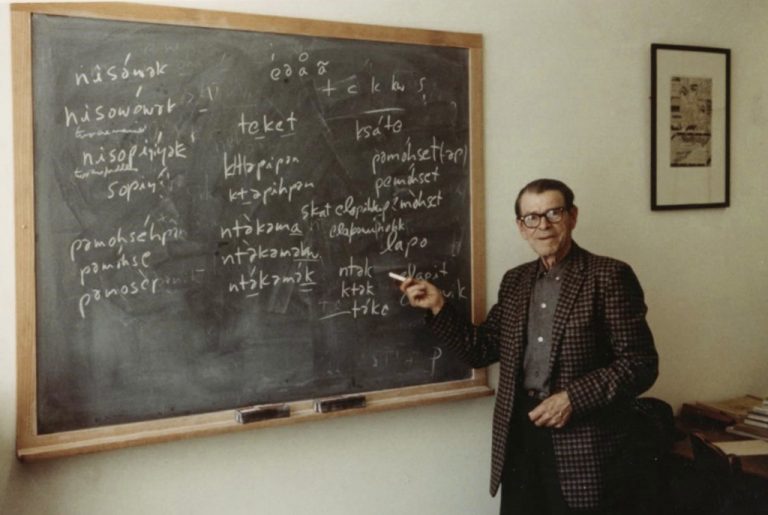

University of New Brunswick Archives 1-53

Read the following quote to your students to demonstrate how difficult it was in the past to keep Indigenous languages alive.

Many of my generation at Listuguj (Listukuj) had parents who knew Mi’kmaw but didn’t speak it to their children. Like my father, they attended the federal day school on the reserve, where they were punished for speaking their language and taught that it had no value. I heard a story that in the 1950s, the priest and the chief went visiting the different households in our community and told parents not to teach Mi’kmaw to our children. They said that the children would go further in life without it. In my time there were no schools on reserve and they bussed us to an English-language Provincial school in Campbellton, so we got very little exposure to Mi’kmaw during our childhood.

Naomi Metallic, Listuguj (Listukuj)

Now try learning five phrases in Wolastoqey or Mi’kmaw by using one of the audio dictionaries listed below. For Wolastoqey Latuwewakon, use Wolastoqewatu!. For Mi’kmaw use the Mi’gmaq Mi’kmaq Micmac Online Talking Dictionary. See if you can use some of these phrases tonight with your parents. Or using the pronunciation key apps at the beginning of this resource unit, learn how to say the following sentence:

Ketu’ Kina’masi ta’n tel-Mi’kmawii’simk

I would like to learn how to speak the Wolastoqey (or Mi’kmaw) language.

Nkotuwokehkims Wolastoqewatuwan

Profile — Elder George Paul and the Mi’kmaq Honour Song

Translated into multiple languages, played accompanied by all sorts of instruments, and performed for audiences around the world, the Mi’kmaq Honour Song expresses a deep inner gratitude that is also felt by those who hear it. The following video describes how Elder George Paul created it.

“There’s a spirit that travels with that song,” Paul said in an interview from his home in Miramichi, N.B. “And I know that because people tell me themselves, it’s like testimonies, they come to me and tell me, ‘That song saved my life.'”

Now a respected elder from Metepenagiag, the idea for the song first came to Paul as a young man on a spiritual fast in the 1970s. It is performed with the accompaniment of drums at all manner of different gatherings — from celebratory pow-wows to mournful marches for missing and murdered Indigenous women and girls.

“It’s a very powerful message, really. Honour who we are as a human family, help one another. Help one another in a manner that the creator has given us here on Mother Earth. There is only one.”

Paul said he’s pleased with the impact his song has made over the decades, and with the opportunities he’s had to share it with different audiences. He’s recorded the song’s chants with Symphony Nova Scotia, and a book about the song is part of Nova Scotia’s treaty education curriculum.

“How a Mi’kmaw song ended up on an album by world-renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma” Taryn Grant (CBC) (https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/nova-scotia/mi-kmaq-honour-song-yo-yo-ma-jeremy-dutcher-1.6202889)

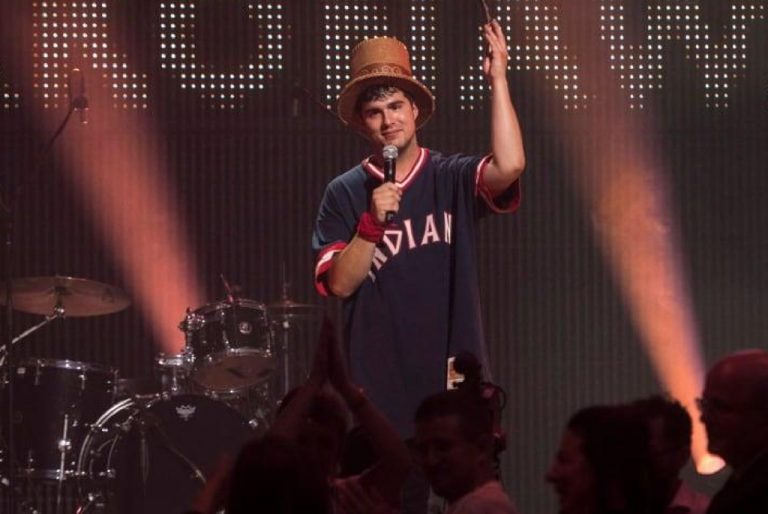

Most recently, Jeremy Dutcher performed the Honour Song with internationally renowned cellist Yo-Yo Ma on his latest album. (https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/national-jeremy-dutcher-interview-polaris-prize-wolastoq-1.4820825)

Start learning this song by singing along with George Paul. Then finally try it without him. A drumbeat will help you keep the rhythm.

Mi’kmaq Honour Song

Kepmite’tmnej Tan’teli l’nuwulti’kw

Geb-mee-day-d’m’nedge Dawn deli ul’new-ul-dee-k

Let us greatly respect Our nativeness

Nikma’jtut Mawita’nej

Neeg-mahj-dewt Ma-wee-dah-nedge

My people Let us gather

Kepmite’tmnej Ta’n wettapeksulti’k

Geb-mee-day-d’m’nej Dawn wetta-beg-sul-deeg

Let us greatly respect Our aboriginal roots

Mikma’jtut Apoqnmatultinej

Neeg-mahj-dewt Abohn-naw-dul-din-edge

My people Let us help one another

(Hey) Apoqnmatultinej ta’n Kisu’lkw teli ina’luksi’kw

(hey) abohn-maw-dul-din-edge dawn Gee-suelk deli ee-gah-lug-seek

Let us help one another according to The Creator’s…

Wla wskitqamu Eye eya

Wulla wuk-seed-hah-moo Way-ah heyo

…intention for putting Us on this planet

Chorus

Wey u we he haiya We u we he haiya

Way oh way ha yah (yah) Way oh hey oh hey ha yah

Wey u we he haiya We u we he haiya

Way oh hey ha ya (ah) Way oh hey ha yah

Wey u we he haiya We u we he haiya We u he haiya

Way oh hey hay yah

Way oh hey ha yah (ah)

Way oh hey ha ya hey yo

Wey u we he haiya We u we he haiya

Way oh way ha yah (yah)

Way oh hey oh hey ha yah

Wey u we he haiya We u we he haiya

Way oh hey ha ya (ah)

Way oh hey ha yah

Wey u we he haiya We u we he haiya We u he haiya

Way oh hey hay yah

Way oh hey ha yah (ah)

Way oh hey ha ya hey yo

REPEAT ENTIRE SONG 4 TIMES

Profile — Jeremy Dutcher

‘Deep listening’: How Jeremy Dutcher crafted his fascinating Polaris Prize-winning album

Sean Brocklehurst · CBC News · Posted: Sep 18, 2018, 3:58 PM ET

https://www.cbc.ca/news/indigenous/national-jeremy-dutcher-interview-polaris-prize-wolastoq-1.4820825

Jeremy Dutcher’s first words after learning he’d won the Polaris Music Prize were yelled out in his traditional Wolastoqey language. “Psiw-te npomawsuwinuwok, kiluwaw yut! All of my people, this is for you!”

When Dutcher, who is from Tobique First Nation (Neqotkuk), switched to English, his words were measured, focused, and sent a strong message to the crowd packed inside The Carlu Theatre in Toronto […].

“Canada, you are in the midst of an Indigenous renaissance. Are you ready to hear the truths that need to be told? Are you ready to see the things that need to be seen?”

Dutcher’s debut album, Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa, was selected for the prestigious Polaris prize as the Canadian album of the year based on artistic merit.

He used his moment in the spotlight to emphatically remind people why he made the album, a fusion of his own operatic interpretations of traditional songs sung entirely in the Wolastoq language.

“To do this record in my language and have it witnessed not just by my people, but every nation from coast to coast, up and down Turtle Island — we’re at the precipice of something. It feels like it,” he said.

“I do this work to honour those who have gone before, and I lay the footwork for those who have yet to come. This is all a continuum of Indigenous excellence, and you are here to witness it.”

A Labour of Love

“This record is a culmination of five years of work, of research, of community engagement, of recording,” Dutcher told CBC’s The National in a recent interview.

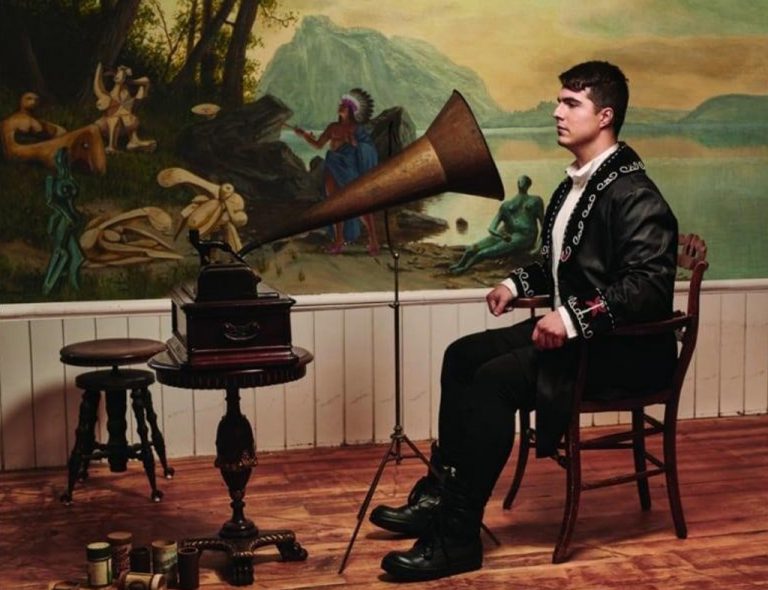

The classically trained operatic tenor and composer from the Tobique First Nation (Neqotkuk) in New Brunswick studied 110-year-old wax cylinder recordings of his ancestors from the Canadian Museum of History, which later became the inspiration for the album.

“When I first got to hear these voices, that work for me was a profoundly transformational moment in my life. It was a process of deep listening — to sit there with these headphones and really hear what these voices had to tell me.”

Dutcher spent weeks inside the museum, meticulously transcribing the recordings once collected by William H. Mechling. The anthropologist lived among Dutcher’s ancestors for seven years in the early 1900s, capturing the songs and voices of the community on wax phonograph cylinders.

Dutcher says he wanted the album cover to represent that process.

“When you look at the album cover you can see wax cylinders on the floor, which were what these recordings were collected on, using the phonograph machine in the middle there. And I’m seated in the chair with this traditional jacket on, I wanted to represent that time that these songs were collected.”

Dutcher adds that he was “very, very fortunate to have a music education and to be able to transcribe what I was hearing, and to write it down, and to be able to take that away and create my own music based on these melodies.”

He adds, “It [the recorded material] is not doing any good sitting on a shelf collecting dust. It has to be with the people.”

Preserving Language

Armed with a notebook filled with transcripts, Dutcher began writing musical arrangements around them, breathing new life into traditional Wolastoq [sic] songs. It’s a language now fluently spoken by fewer than 100 people, and one his own mother was punished for speaking while growing up.

“She went into the church-run day schools at a very young age, when she was six years old. You weren’t allowed to speak your language there. In fact, you were physically punished if you did. And the elders knew this, and so they said it’s better if we just don’t speak to the kids in the language.”

“So, I think the shame that she felt in those schools, that was sort of relayed down from generation to generation. And so that is why I turned to the archive [of recordings]. I think it’s important for people to understand a true history of what has actually happened, and what continues to happen in this country, around the systematic devaluing of Indigenous languages and cultures.”

Dutcher says his generation needs to understand the importance of their Indigenous languages.

“If the younger generation doesn’t start to reclaim and revitalize our language, we’re going to lose it forever. When I came into a better understanding of my language, I started to understand my place in the world a little bit better and started to relate the world around me differently.”

“I think for me, what this project allowed me to do was to sit down with my mother and my elders in my community and ask them about their lives. To say, ‘what was your experience of music growing up? What did your community sound like growing up?’ And understanding that the circle was never broken. That we’re all just part of one continuous artistic lineage of Wolastoq [sic] song carriers.”

After five years of work on Wolastoqiyik Lintuwakonawa, Dutcher says he’s not finished with the project. The young composer is ready to take it to an entirely different stage.

“For me, the journey is not yet complete. There are still so many stories to share. I hear symphonies in 2019, 2020. See you there!”

Other articles about Dutcher:

- Jeremy Dutcher wins Polaris prize for Wolastoq-language album

- Voices from the past: Musician Jeremy Dutcher gives new life to wax cylinder recordings of his ancestors

- Polaris prize nominee uses original recordings of ancestors singing for a new album

Videos:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ozrsHvEPzMk Interview

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tQMrl-hPnUg Honour Song — This song was composed by George Paul

WATCH with your students: The CBC National’s interview with Jeremy Dutcher

Describe to the students what Jeremy Dutcher has accomplished. Play the audio recording of The Honour Song and show his album cover.

Evaluation

Ask:

- How has this music helped to preserve language?

- How do you as young people feel about having a contemporary artist re-record this music that was originally recorded over one hundred years ago?

- Do you know any songs that have been passed down through your families?

- If so, write the words in your notebook.