Materials required: photocopies of the two stories, notebook

Presented below are two stories connected to food on the reserve — one is a personal story about the control the Indian Agent had on the reserve and the power he exhibited over people. The other concerns the gratitude shown by the Mi’kmaq people in Amlamkuk Kwesawe’k (Fort Folly) to the people of Dorchester at New Year’s. It is a public story and was written for the newspaper.

The emphasis of this activity is to show how people from two groups develop their own perceptions. The objective is to compare and contrast these two stories.

It happened this way. My father had found work with a sawmill that was forty-eight kilometres from our home on the reserve. We did not own a car; in fact, there was only one Mi’kmaw on the reserve who owned a car at that time, and it was an old clunker that was not working half the time. Therefore, he had to walk to work on Sunday afternoons and walk home on Saturday afternoons — that was the plan.

We ran out of food on Friday of the first week he was away and, as fate would have it, Dad couldn’t make it home that Saturday. Early Monday morning, very hungry from going two days without food, I set out with my mother to walk about five kilometres through the woods to the state-run Indian agency farm, located on the other side of the reserve. We arrived shortly after the agency opened for the day at 8:30 a.m. and were sent into the Indian agent’s office to meet with him. Mom explained the situation, and without any consideration, the agent refused a ration because he knew that my father had found a job and was working. How he knew, I cannot tell you. She started crying and begged him to have pity on her eight hungry children and told him she wouldn’t be there if her husband could have made it home. He finally relented and told her that he would reconsider his decision.

At 11:45 a.m., shortly before the well-fed Indian agent went for lunch, he called Mom back into his office and gave her a small food ration. I can remember all this as if it happened yesterday. My reaction, as I looked at the mean Agent, was “when I grow up, nobody like you is ever going to do to me what you’ve done to my mother!”

Daniel N. Paul Racism and Treaty Denied in Living Treaties p. 179

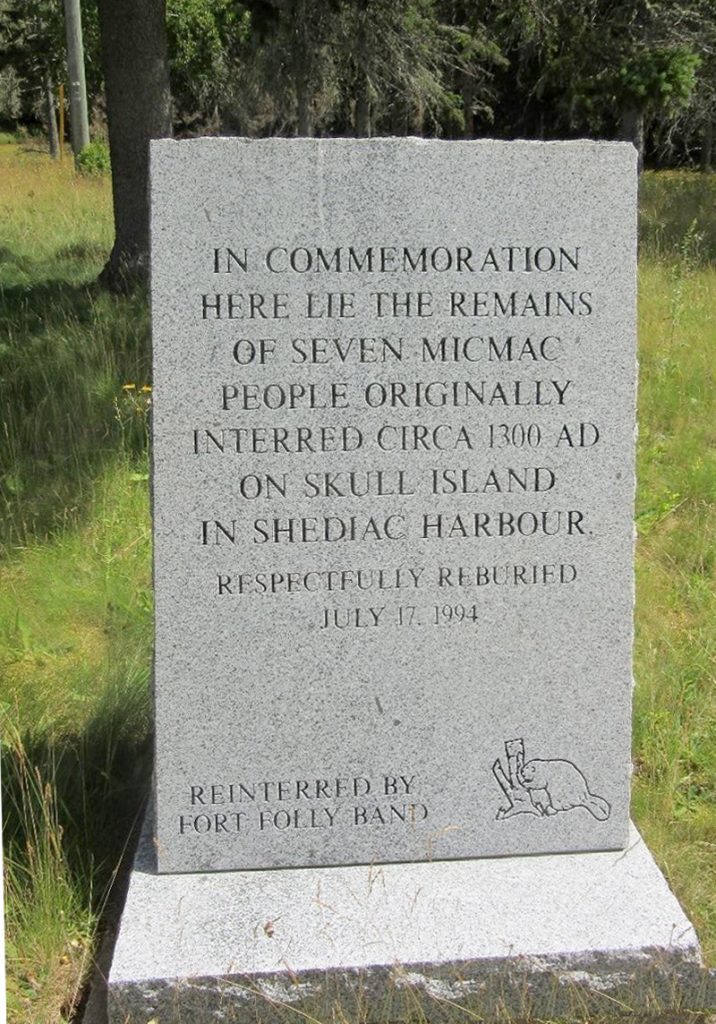

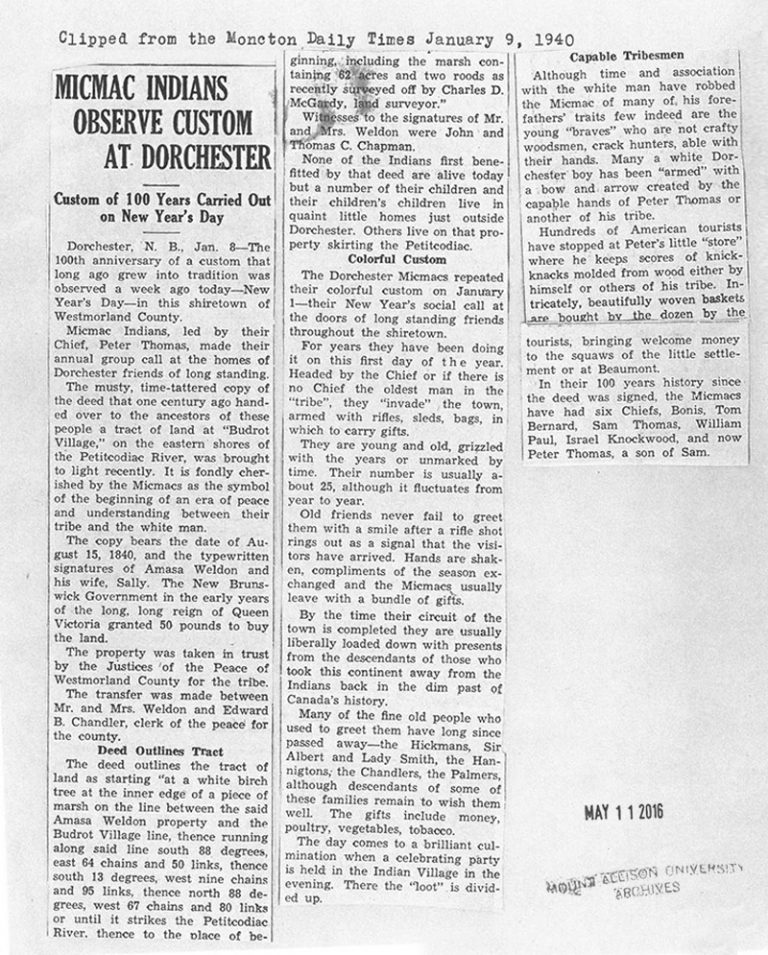

Beaumont, now Amlamkuk Kwesawe’k (Fort Folly), is the most southerly of all Indigenous communities in New Brunswick. Initially, it was considered a special status reserve because a parcel of land was set aside for the exclusive use of the Mi’kmaq prior to the Confederation of Canada. The land was purchased from Amos and Sally Weldon in August 1840 at the junction of the Memramcook and Petitcodiac Rivers. Not only did the French and the Mi’kmaq both live on the same reserve land set aside by the government but they also shared the Chapel at Beaumont, the same post-office and their children attended the same schools. By 1900 the population had declined because resources were limited on this point of land. The land was sold, and new land acquired nearer to Dorchester. The last people left Beaumont in 1955, but the Chapel still stands and there is a cemetery and a grotto close-by. In the cemetery are also the remains of Mi’kmaq from Skull Island in Shediac Bay, dating back 700 years. These remains were removed from their traditional resting place due to erosion. The new community of Amlamkuk Kwesawe’k (Fort Folly) has about 100 people.

Until 2020, it was taught by Gilbert Sewell, an Elder from Ke’kwapskuk (Pabineau First Nation), who passed in March 2021. Paths which encircle the community are open to the public and inform people about the medicinal value of native plants (see http://www.fundy-biosphere.ca/en/hiking-trails/fort-folly-firstnation-medicinal-trail.html for more information). The community of Amlamkuk Kwesawe’k (Fort Folly) participates in the St. Anne’s Day celebration in August each year. A special mass is held in Beaumont where members give thanks for all they have. They give thanks also for their neighbours and friends who are not part of the First Nations Community. They all celebrate together with a large offering of wild foods such as salmon, lobster, and moose. They usually get 300–400 people out for this day, tripling the community’s population.

Note: a link is about 20 cm. One hundred links make a chain.

Activity – Comparing Reserve Stories

Have members of the class read the two stories aloud while the remainder of the class looks at the photographs. In their notebooks, have them write responses to the following questions:

- Who is talking in each story? Is each story told by an Indigenous person?

- How many people are involved in each story? Write down who they are.

- Where does each story occur? Is this a public or private place?

- Are there words or expressions in these stories that you do not understand? List some of them.

- Are there expressions that make you feel uneasy? Why? List some of them. Why do they make you feel this way?

- Which story is personal, and which one is intended for a large audience?

- How does each story make you feel? Describe your own emotions about the story.

- Each story talks about the giving and taking of food. Write your own story about an event in your life when you have given or taken food.