Student Learning

I will be able:

- To understand how a society’s environment influences its development

- To examine how ways of seeing, knowing, and learning are interconnected with an understanding of the land

- Simulate an archaeological dig and identify artifacts used by Indigenous peoples, while placing them in a timeline (Activity 1)

- To give examples of ingenuity displayed by the Waponahkiyik

- To recognize that Indigenous peoples have lifestyles, customs, and traditions that are unique to each Indigenous society (Activity 2 and 3)

- To explore how people used the land in the students’ community before it was founded, as well as in nearby areas. (Activity 1)

- To appreciate the role of a long-term relationship between a community and its environment and the beliefs on which this relationship is based

- To understand how Elders serve as knowledge keepers and the importance of storytelling in expressing worldviews (Activity 2 and 3)

- Design a summer camp program that illustrates the seven teachings of Indigenous cultures (Activity 3)

Of the web of life, man is merely a strand in it. Whatever man does to the web, he does to himself.

Chief Seattle, 1786–1866

Chief Seattle was a Suquamish and Duwamish chief in the area that is now known as Washington State. He argued in favour of ecological responsibility and respect for Indigenous land rights. The city of Seattle is named after him.

That we held, and still hold, treaties with the animals and plant species is a known part of tribal culture. The relationship between human people and animals is still alive and resonant in the world, the ancient tellings carried on by a constellation of stories, songs, and ceremonies, all shaped by lived knowledge of the world and its many interwoven, unending relationships. These stories and ceremonies keep open the bridge between one kind of intelligence and another, one species and another.

Linda Hogan, “First People” in Intimate Nature: The Bond Between Women and Animals. Quoted at https://qonaskamkuk.com/peskotomuhkati-nation/about-treaties/

Combining lived knowledge and its unending relationships together with science is called Etuaptmumk, “two-eyed seeing”, a term proposed by Mi’kmaw Elder Albert Marshall in 2004. You can find out more about this subject at https://trauma-informed.ca/trauma-and-first-nations-people/two-eyed-seeing.

Teaching Indigenous history by focusing on treaties does raise several issues, not least the risk of viewing the past exclusively through a settler (non-Indigenous) lens based on erroneous or incomplete concepts. For instance, the language of the treaties refers to the Indigenous peoples as “Indians” even though the Indigenous peoples in Canada are not from India. Likewise, this land was not “discovered” by Europeans, as settler history often has it; there were Indigenous peoples living here long before the first settler set foot on these shores. A related question is the one that archaeologists raise about whether the people in the prehistory period — by which they mean the time before written records, and therefore prior to Europeans — were different people than those who interacted with the Europeans once they arrived. Differences in stone tools that have been found, and in historical burial customs, have led archaeologists to believe that different waves of people have inhabited this area over time. Yet First Nations people have oral traditions that indicate they have been here since time immemorial. It is important to address these questions while studying this lesson.

In order to understand the interrelationships between Europeans and Indigenous peoples, as well as the Treaties they signed together, it is important to understand that the lifestyle of Indigenous peoples altered with the arrival of Europeans and later of settlers, due to the changes that were imposed on them.

To the Waponahkiyik, the idea of a period of time that is “prehistory” because it is not written down does not exist. The Waponahkiyik relied on oral history which was passed down by word of mouth in important communal settings over many generations. For example, Klu’scap/Glooscap/Keluwoskap stories, which you may have read elsewhere in the Grade 3 or 4 units, often talk about the disappearance of gigantic animals. These stories could in fact refer to some of the early animals, now extinct, who once lived in our environment after the last Ice Age. Take, for instance, the model of the mastodon you see on the highway outside Debert, Nova Scotia: it reminds us that gigantic mastodons, now extinct, were once hunted by the Waponahkiyik. The term prehistory suggests that the oral stories of the Mi’kmaq, Peskotomuhkati (Passamaquoddy) or the Wolastoqewiyik are not history at all and not as correct as those written down by Europeans. There is little understanding that the oral tradition was part of an Indigenous worldview, not a European one, nor that oral traditions the world over have been shown to be highly accurate. It is no wonder, then, that there is a basic misunderstanding about how to interpret the Treaties that define the present-day relationship between settlers of European ancestry and Indigenous people. The court systems structured by Europeans still have not addressed the oral truths of Indigenous peoples.

This first lesson was developed to show how Indigenous peoples interacted with their environment and to simulate how a society is formed over several millennia by the connection between its people and their environment. Its intention is to develop an understanding with the students as to why Indigenous peoples would never agree to give up their relationship to the land, and therefore why land is not mentioned in any Peace and Friendship Treaty.

This first lesson on Treaties shows the long evolution of the Indigenous peoples in New Brunswick and their intimate relationship with their surroundings. As Linda Hogan describes this relationship, it is both “interwoven” and “unending”. Some material in the next section, Cycles of Life, has already been discussed in Grades 3 and 4; it is important for the students to understand how lighting was used in hunting in order to do the follow-up activity. Hunting always involved an acknowledgement that the animal had given up its life for the survival of people.

The cycles of life

A series of films created by the Nova Scotia Department of Education on the seasonal life cycle of the Mi’kmaq can be shown to explain hunting and fishing practices as you work through this lesson. http://learn360.infobase.com/p.ViewVideo.aspx?customID=287SOM. This link may require a password. You can apply for one.

As you discuss the changing seasons with your class, have each individual make an imaginary map of the area occupied by Mi’kmaq, Passamaquoddy or Wolastoqewiyik.

Have the students show on their map:

- what season it is when this area is occupied;

- where the limits (boundaries) of the area might be;

- where different food sources might be found;

- routes of travel between their seasonal dwellings;

- in which season, and where, would they come together to share in obtaining food and celebrating.

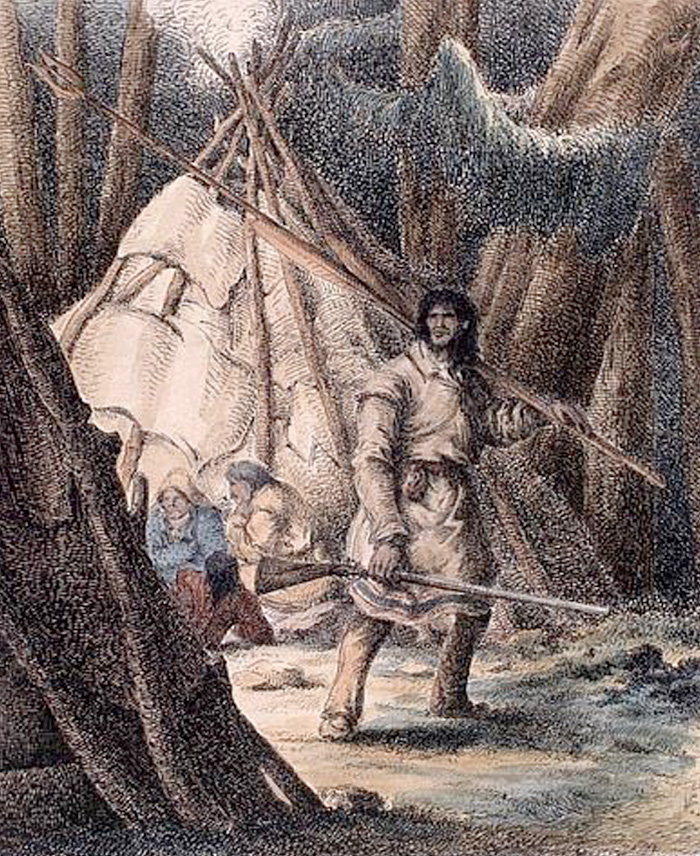

Most Mi’kmaq, Passamaquoddy and Wolastoqewiyik built wigwams in the shelter of the forest to hunt there during the winter, while in summer they lived near the coast, where they could fish. They knew many ways of hunting and fishing and their methods varied with the changing seasons and the habits of the animals and fish. This could include spearing salmon and trout by torchlight at night, in pools after the fish had jumped waterfalls. Sturgeon and bass were taken from the sides of canoes as they circled into a rim of light made by burning torches. Bag nets were used to catch eels and other small fish. The bag net was placed in the narrowest and shallowest part of a river. Often a fish weir was used.

It is believed that Indigenous peoples in New Brunswick may have obtained as much as 90% of their food from fresh or salt water.

In the summer, activities revolved around fishing, drying and salting, berry picking and cultivating the land.

In winter, during hibernation, bears were searched for in the hollows of trees. Often, they were found where the vapour of bear’s breath could be seen. Then, the hunters drew out the bear and attacked it with spears. Ceremonies were carried out to show that it was understood that the bear had sacrificed its life and was providing Sacred Bear Medicine to Elders. The same was true for the hunting of most animals.

Bows and arrows were used to hunt beavers. Sometimes, traps were set with a strip of aspen as bait, and the beavers were caught before they could get away. Their houses were left intact.

Moose was a favourite food and they could be hunted in the fall and winter. To find moose, Waponahkiyik would examine twigs: from the taste of the broken end of the twig, they could tell how recently a moose or deer had passed that way. Before the innovation of bows and arrows, about 2000 years ago, people used atlatls to hunt large game animals. An atlatl is a slightly curved piece of wood which is held in the hand. At one end, it has a small wooden point which fits into the notched end of a spear. The atlatl acts as a lever or an extension to the thrower’s arm, increasing the spear’s speed and the distance it can cover. A spear that is shot with the help of an atlatl can reach a speed of 100 km/h over a distance of 200 metres.

Later, Indigenous peoples started to use bows and arrows. In winter, they would stalk moose and deer. Sometimes dogs were used to force large animals into the deep snow until they fell from exhaustion. To entice their prey within range of their arrows, Waponahkiyik had a call for every animal. When hunting deer, for example, they used a snort to imitate a stag. Another trick was to let water fall out of a birchbark dish and make a cow moose’s cry: a bull moose might come to the river.

A prayer of thanks was given to all animals that had given up their life for the survival of people. Women usually collected the meat that had been harvested. There was a community celebration, and the meat was shared with all those nearby.

Summer was a time of plenty, with meat, fish, fowl and fresh eggs in abundance. At such times of plenty, the hungry days of winter were remembered, and food was put away to get through them. Meat, fowl, fish, and shellfish and lobsters were smoked and sun-dried; berries were boiled and shaped into cakes to be used in soup. Egg yolks were boiled hard; bones were broken and boiled for the marrow; fat and oil were stored in seal bladders. In summertime, people often planted gardens of corn, beans, and squash. This was especially true of Wolastoqewiyik, who often planted along the Wolastoq (Saint John River). However, there was never enough gardening to hold people in one place for a long time.

When there was a scarcity of fish or game, Waponahkiyik moved to a new place, often a long distance away. The environment that Indigenous peoples were born into was best suited to seasonal use. Following the earth’s rhythms, families travelled and constructed wikuo’m/wigwams/wikuwam, from where they could hunt, fish or plant.

Today, some of these hunting methods may appear cruel. This is not an Indigenous viewpoint. Indigenous peoples grew up with the perspective that humans are equal to or of less importance than all other creations on Mother Earth. They celebrated the animal or fish that gave up its life so that they could survive. Today, freedom to use the Earth in this way has been restricted and the security of pursuing an independent, resource-based life of cultivation, fishing and hunting has been challenged by laws and regulations created by Canada and the provinces. This has had a major effect on Indigenous people’s right to self-sufficiency.

Indigenous people generally do not hunt for sport, they hunt for food, and in Canada they have a constitutional right to do so. The Supreme Court of Canada has upheld this right, but several provincial courts have not and Indigenous people have been arrested for hunting at times when settler law said such hunting was illegal. In 1928, Grand Chief Gabriel Sylliboy was charged and convicted with hunting muskrats out of season even though it was within his Treaty Rights.

Out of this life of following the seasons, the Waponahkiyik developed a rich worldview. It contained a set of values and beliefs that created a distinct identity and provided a feeling of belonging to a group and a connection to ancestry. In Grade 4, students studied how the worldview of Indigenous peoples was that all things, both living and inanimate, were related — land, animals, water, human beings, plants, customs, and laws. Based on thousands of years of history continuing to the present day, Indigenous life is grounded in interdependence, reciprocity, and gratitude. Their worldview says as much about how something is done as it does about what is done. Indigenous belief remains that resources and the harvest are to be shared. It was understood that only what was needed was taken, and that what was left was for others and for rejuvenation and regrowth. Indigenous people did not hunt all year long (e.g.: bear was not hunted in summer). They understood that time was required for animals to procreate and nurture their young.

How one lives one’s life and how one thinks about it — one’s consciousness as a person — was highly regarded. From customs and codes of conduct came how life was practised. Indigenous peoples valued shared use of the land that was defined as the territory on which their Nations lived. This perspective or worldview was quite different from that of the Europeans, who valued independence, individual ownership and economic success.

Wisdom of the Elders

Ah, the truth. What is our truth? Each person must begin from his or her own personal experience … Speak truth to power

Carolyn Kenny and Tina Ngaroimata Fraser, Living Indigenous Leadership p. 200

This Indigenous worldview was communicated to other members of the group by the stories of Elders. An Elder has to have lived through a variety of experiences and be able to connect people to the events, customs, and ceremonies of the past. They also act as counsellors, but do not impose their knowledge and wisdom. They listen patiently and without judgment. Today, they often combine spiritual values with their experiences in life and provide suggestions or make observations. Elders represent a wisdom that is based in a tradition of thinking, reflecting, living and being. Through establishing the relationships of one thing to another, the Elders ensure that these interrelationships make all people responsible for their actions.

Wabanaki in New Brunswick have retained sovereignty, their knowledge system, freedom of religion and the belief that the land is theirs. They still consider these values their ancestral rights.