Student Learning

I will be able:

- To hypothesize on the impact of European religions on the lifestyles of Indigenous peoples (Activity 2 and 3)

- To identify changes in lifestyle and how consequences can be both positive or negative and their long-term implications (Activity 3)

- To describe how the fur trade changed Indigenous life forever (Activity 3)

- To participate in the debating and rebuttal of the differing points of view on land ownership (Activity 1)

They are astonished and often complain that since the French mingle with and carry on trade with them, they are dying fast, and the population is thinning out… One by one the different coasts according as they have begun to traffic with us, have been more reduced by disease.

Père Biard, 1610 in Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents edited by R.G. Thwaites 1896 vol. 1:77

Originally, we were given birth by Mother Earth. We were part of Mother Earth. She didn’t belong to us. We negotiated our survival through ceremonies. So, we didn’t ask questions.

Stephen Augustine, Hereditary Chief of the Mi’kmaq Grand Council, June 17, 2020

This lesson deals with the interplay of the fur trade, religion and colonialization and the major impact these had on where Indigenous peoples lived, what they were able to hunt, and their interactions with each other. Activity 2 is oriented towards Mi’kmaq and Activity 3 is oriented towards Wolastoqewiyik. Activity 1 is important for understanding settlement.

The Fur Trade

Hunting as practised by Indigenous peoples was more sustainable before Europeans arrived. The Wabanaki harvested animals only as they had need of them. When they were tired of one animal or found it scarce, they harvested something else. They never accumulated a collection of skins from moose, otter or beaver, but only hunted them as they needed for their personal use.

With the arrival of the first Europeans things started to change rapidly for the Waponahkiyik (Wabanaki people). Metals replaced stone, bone, and wooden tools. Guns replaced arrows and spears. Cotton and wool replaced painted leather and quill clothing. In return for these items, Europeans wanted the furs of forest animals such as mink, otter, weasel, muskrat, and beaver to use in their clothing and as adornments (such as hats). This meant that Wabanaki hunters had to change where they lived in order to spend more time in the forests that these animals inhabited or along smaller streams. So much time was spent there trapping that the Waponahkiyik no longer had time to hunt along the coast. They became less self-sufficient. Instead of hunting to feed themselves, they became dependent upon European food such as dried peas, dried fruit, stale flour, and hard biscuits. This food was not as nutritious as the food that they had hunted, fished, or gathered for themselves before. Soon sickness became rampant (this subject is discussed more fully below). Whole communities of Wabanaki died. For additional information, see the website below.

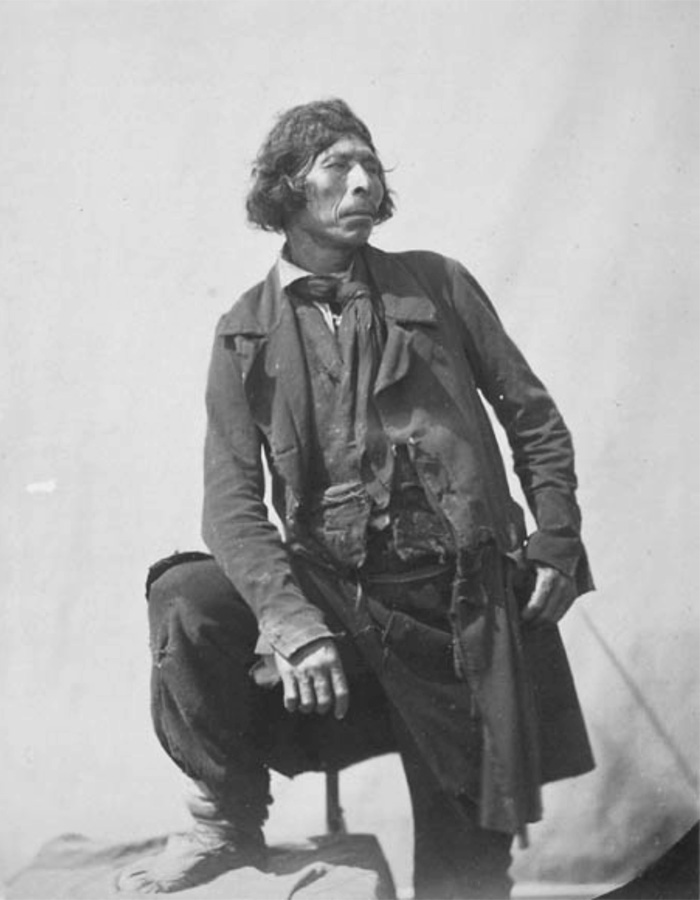

Library and Archives Canada 3368577

As Indigenous peoples became dependent on the fur trade, guns made it much easier to hunt, especially on a grand scale. As early as the late 1600s, guns were causing some game to become scarce. The balance of nature was changing. Settlers started to hunt as well. With so many hunters going after them, the beaver population was greatly affected. Only the Elders still knew how to make things like stone tools. By the late 1700s, it was impossible for Wabanaki to return to a life completely without trade goods.

Trade with Europeans also brought other new problems. It introduced alcohol to Indigenous peoples and also brought new diseases. In addition, Europeans did not appreciate the value of items that were time-consuming to make, such as porcupine quill work, and did not offer a fair price for these.

Effect of Disease

Indigenous identity was stretched thinner and thinner by successive waves of disease. Indigenous peoples had no natural immunity to the viruses that Europeans carried with them, such as the ones that cause colds, typhoid fever, measles and smallpox that Indigenous populations had not experienced before. Epidemics spread quickly — often several diseases at once. Within 100 years of the first Europeans’ arrival, 75% of the Indigenous peoples in North America had died. Not only were numbers severely reduced, but in a culture with no written language, as Elders died, so history and tradition were lost. As Indigenous peoples tried to understand what was happening to their society, they turned to their spiritual leaders called puowin (shamans). These puowin could heal the sick by using certain plants. They also acquired guardian spirits to help them in their healing. Where this had been effective before, the Waponahkiyik could see that European traders and priests were usually unaffected by the diseases that were claiming so many of their family and friends. Their own puowin and healers were powerless in the face of these new epidemics. Think about how diseases and death would have changed Wabanaki life. How would fishing and hunting, travelling, and trading have been affected?

Conversion to Christianity

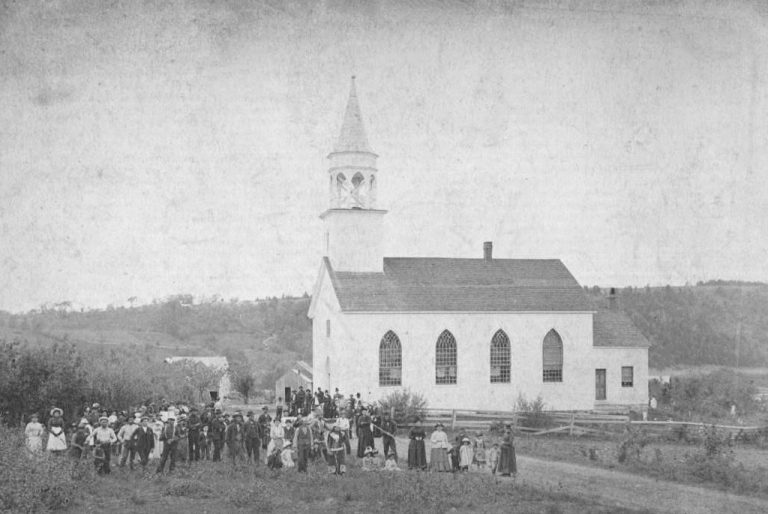

As French Catholics and English Protestants vied for the souls of Waponahkiyik, many people did convert to Christianity with the hope that they would become immune from diseases. In 1610, the Mi’kmaw Saqamaw (or chief) Membertou became the first Mi’kmaw to become Roman Catholic. This resulted in a long relationship between the Mi’kmaq and the Catholic Church that continues to this day. However, some Wabanaki rejected the European religions outright, and others adopted an approach that blended elements of the old and new religions. For example, Margaret Labillois, an Elder from Eel River Bar (Ugpi’ganjig), stated that the Mi’kmaq interpreted some fossils as Klu’skap’s fish bones from when he overturned his pot in annoyance with the missionaries changing his people’s ways.

While some Indigenous people converted to Catholicism, many of them still maintained their traditional knowledge and spiritual belief system, creating a blended form of Catholicism. This could be an attempt to reject assimilation. For example, Klu’skap/Keluwoskap’s grandmother with her ability to heal is sometimes understood as being St. Anne, the patron saint of the Mi’kmaq.

Mi’kmaq believe that Chief Membertou, through his baptism, accepted Christianity as part of an agreement with the papal court (the Holy See) in 1610. Because of this, two holy days are kept sacred — Pentecost Sunday and the feast of St. Anne (see Activity 2 and 3). Under the Mi’kmaw Treaties, the Mi’kmaq’s Catholicism, founded on their own spirituality, ensured protection of their own practices in education and other traditional aspects of their lives. View the videos on ceremonies from Culture Studies Videos — Wabanaki Collection to better understand Wabanaki traditions such as sweat lodges, smudging ceremonies, and talking circles.

Settlement

For the Wabanaki, land was not marked with boundaries or claimed as property. Although groups of people regularly frequented certain spots — such as campsites, canoe and portage routes, footpaths, and burial grounds — they did not view them as something they possessed. Still, these places gave them a deep sense of belonging. Although they did not consider that they owned the land, it defined who they were.

Initially, Acadians settled and interacted with the Wabanaki, until the expulsion of the Acadians in 1755. Later, as large numbers of British settlers and American loyalists began to settle in what had been Waponahkiyik territory, the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqewyik and Passamaquoddy could no longer use all the places where their ancestors had once lived seasonally. They did not try to exclude European settlers from using the land, but they also did not think of selling or giving them parcels of land — or even that this was something that could be done. These new immigrants also valued the coastal areas for the same reasons that the Wabanaki had — so they took them. It was only once great numbers of settlers arrived and colonial governments began to take control that the Waponahkiyik realized that they were losing the land itself, together with all its resources, permanently. The Wabanaki were forced back into the forest, where it was harder to find food.

As a result of all these factors — malnutrition, growing dependency on material goods that had to be exchanged for furs, and conflict — the populations of the Waponahkiyik declined even more rapidly. Resilient, they found a way to survive and they adapted to the new changes. Their way of life changed, but it did not die.

Evaluation

As you complete this lesson, ask the students to reflect on the following:

Many of the early accounts mention that winter could be a time of starvation for the Indigenous peoples if hunting was poor. Yet we also know that the Waponahkiyik knew how to preserve meat, fat, fish, nuts, and berries. What do you think?

- Maybe the Waponahkiyik didn’t starve?

- Maybe they didn’t know how to preserve food, or they couldn’t preserve it long enough.

- Maybe accounts of hunger and starvation refer to the time after Waponahkiyik had begun trading furs with the Europeans. If this is true —

- The Wabanaki didn’t have enough time to lay in a supply of food for the winter because they were too busy trapping animals for fur.

- Before the Europeans came, the Wabanaki did not depend on hunting in the winter. The fur trade forced them to hunt all winter, taking them away from the coast, where their preserved food was stored. Ordinarily, they would have gone hunting inland only in good weather.