Student Learning

I will be able:

- To appreciate the significance of regalia when negotiating treaties

- To design a coat and hat by using traditional curved motifs used in regalia in First Nation Schools

- To understand that language eradication policies had a great impact on Indigenous individuals and societies

- To speak a phrase or learn some simple conversational responses in Wolastoqey Latuwewakon or Mi’kmaw

- To listen to Jeremy Dutcher’s music and understand its ancestral connection to language

- To explore Wabanaki protocols in issues of governance

- To achieve consensus on a solution to an environmental issue at a youth summit

- To hear and learn the Mi’kmaw Honour Song

While there are many important aspects of our traditional governance systems, the commitment to consensus building – not just the final decision itself – is what stands out as one of the keys to restoring balance today.

Pamela Palmater, Indigenous Nationhood, p.2

Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqewiyik and Peskotumuhkati (Passamaquoddy) who signed treaties expected to maintain their forms of social and cultural organization, their spiritual beliefs, and the skills and knowledge they possessed related to economic development for their communities and for future generations. From their position, these treaties created a living relationship that continues to constantly change today to reflect the current realities for both First Nations and other Canadians.

In this lesson, the students will be asked to analyze the challenges and opportunities associated with the cultural understandings negotiated within the treaties. These include governance and communication among groups, preservation of language and cultural practices and why Indigenous peoples believed there were benefits to both European education and traditional ways of learning. Many of the challenges in upholding these understandings have now started to become opportunities as the Canadian public recognizes that its institutions must be decolonized before Indigenous groups can really move forward.

Shows much ribbon work, beadwork, and trade silver.

New Brunswick Museum/ Musée du Nouveau-Brunswick X14917

Roles of Women and Men in Governance and Treaty-making

Unlike in many other societies around the world, both women and men had important roles in governance within Wabanaki society, including among the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqewyik and Peskotomuhkati (Passamaquoddy). While the Chiefs were often men, many of these leaders were appointed, counselled, and removed by women (sometimes grandmothers). Today, there are several chiefs in New Brunswick who are women. Women have always been valued as the life-givers of their community, but they can also be hunters, warriors, political negotiators, or political strategists.

Traditionally, each group of villages has a District Chief and District Council. The Council includes Band or village chiefs, Elders, and other distinguished members of the community. The Elders, both men and women, were and are the most highly respected. Their advice and guidance were essential, and no major decision was made without their full participation. These Councils and District traditionally had power to make war or peace, settle disputes, allocate hunting and fishing areas to families, etc.

When the Elders summoned a Council Meeting, it would open with a prayer ceremony, after which one of the chiefs would speak to the issue at hand and also make reference to personal experiences. It was the Elders who designated those who would negotiate affairs between families and nations, and choosing a suitable candidate was taken seriously. The Elder would inform the delegate of his task publicly and announce the terms of agreement specified by the Elders.

Today, to Mi’kmaw and Wolastoqey women, leadership means doing the work necessary to move the community forward. Many Wabanaki women have taken up efforts in Aboriginal Rights through education, activism, art and writing. They are compelled to do this through tradition, culture, and spirituality. Yet the challenge for them, especially in education, is enormous. In the fifteen First Nations communities in New Brunswick, there are no high schools.

Language

My language was broken.

Richard Silliboy, Aroostock Mi’kmaw First Nation

Vice Chief

Language is one of the biggest pieces of our culture to ensure we remain sovereign. You can have political sovereignty, but you can’t have cultural sovereignty without the language.

Wayne Newell, Passamaquoddy

Scholar and educator

It is only through our language that we can truly understand the teaching of our ancestors and retain the important wisdom and teachings within it about our treaties.

Joe B. Marshall, Mi’kmaw

Treaty Advocator

Knowledge is what you learn when it gets to your heart. When you repeat it, it becomes wisdom.

Elder Imelda Perley, Wolastoqewiyik

Language is one of the most fundamental ways in which members of a culture or community relate to each other. Language is how people understand the world in which they live and the values that they share. It is estimated that of the hundreds of languages originally spoken in North America before the Europeans arrived, by the mid-20th century two thirds were extinct. In New Brunswick, for example, today there are approximately 6700 Wolastoqewiyik, yet only 100 of them are still speakers of the language. Teaching both Wolastoqey Latuwewakon and Mi’kmaw languages in schools is of critical importance. There are two spelling systems to write Mi’kmaw (Francis/Smith and Pacifique). This resource is using (Francis/Smith) and one spelling system for both Wolastoqey/Passamaquoddy (Francis/ Leavitt).

Have students view the Kinship section of the Wolastoqewiyik and Mi’kmaw Culture Studies videos by Imelda Perley, at 19:00 minutes in the ‘Identity’ video at Culture Studies Videos — Wabanaki Collection. In this section, she explains how the language used in identifying kinship expresses relationships within a clan and recognizes people’s place within a society by demonstrating their relationship to other members of the community. The very terms used to acknowledge these relationships show both love and respect for the people they refer to.

Every person’s cultural identity is formed by language and losing one’s language therefore erodes that identity. The residential school policy severed the bond between Indigenous children, their families and their communities, particularly the connection with the Elders. These schools eliminated or severely reduced the role of Elders in the education of Indigenous children. In many cases, Indigenous languages became threatened. The loss of language impacted cultural identity in other ways — for instance, the importance of ceremony, song, chant, dance, and storytelling was diminished or lost. (For more on this, watch the entire ‘Identity’ video at Culture Studies Videos — Wabanaki Collection, particularly the section on regalia). The transfer of knowledge from one generation to another was severely restricted.

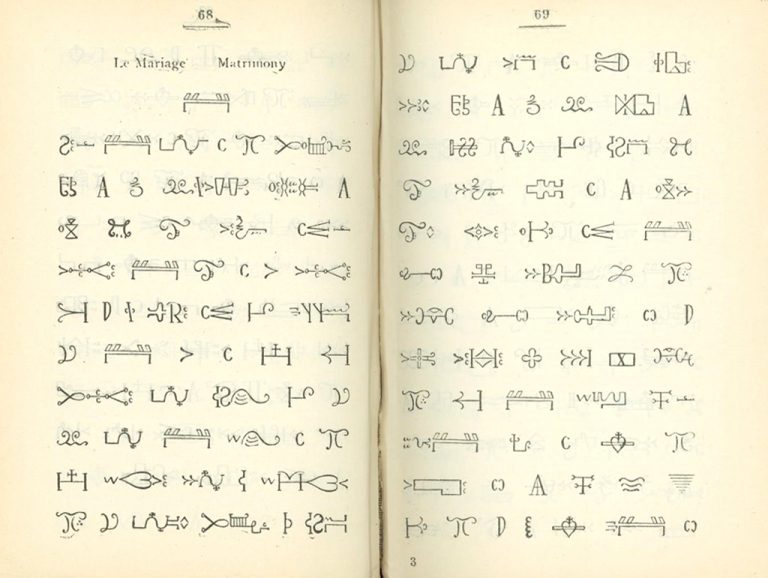

To complicate matters, Indigenous languages were entirely oral — that is, there was no tradition of writing them down. Today, orthographies (systems for writing language) have been developed for all currently spoken Algonquian languages. There is one alphabet used to write for Wolastoqey–Passamaquoddy, and two different systems used to write Mi’kmaw. As shown in the picture above, other orthographical systems were tried, but these proved to have serious limitations for communicating with others.

Algonquian languages are structured differently from European languages such as English. Wolastoqey–Passamaquoddy and Mi’kmaw have many of the same parts of speech as English — nouns, verbs, pronouns and conjunctions — but the modifying words that English speakers use, like adjectives, are built into their nouns and verbs. This means that a single word in Passamaquoddy, Wolastoqey or Mi’kmaw may contain as much information as an entire sentence in English. This makes for languages of great flexibility, in which words are continually “invented” by combining elements in new ways. However, mainstream education programs based on the English and French languages teach reading according to a linear, prescriptive structure that does not allow for the idea of concurrently holding several related ideas in one’s mind. This makes it difficult for young people to learn to read in one of the Wabanaki languages.

There are also words in these languages that have no English or French equivalent. “Nekm,” for example, means “he” or “she,” without specifying gender (non-binary term). This avoids the problems that arise in English where you either need to use “he” when referring to people of both sexes (and risk offending half your listeners), rely on clumsy constructions such as “he/she”, or resort to “they,” which has become increasingly accepted.

Language determines how we perceive and think about the world around us, and we can use language as one way of attempting to understand another culture. Many words that are nouns in English, like ‘wju’sn/wind/Wocawsonuhke,’ ‘metu’ma’q/storm/’tamoqessu’, wastew/snow/psan,’ ‘kikpesan/rain/komiwon,’ and even ‘tepkunaset/moon/nipawset,’ are verbs in Passamaquoddy, Wolastoqey Latuwewakon and Mi’kmaw, as are time words, like ‘na’kwek/day/spotew’ and ‘newtipunket/year/pomikoton.’ From the Indigenous viewpoint, they are processes rather than things.

To European language thinkers, this approach to language may seem scattered and unfocused. Native-language thinkers, on the other hand, may find the linear way of thinking rigid and narrow. Indigenous people commonly approach an idea or a topic from many different angles at once, thinking in a circle rather than a line.

Robert W. Leavitt, 1995, p. 10

People of European descent tend to attack a problem by formulating a hypothesis and then testing it, whereas Indigenous peoples observe the problem from “different angles at once” and resolve the problem by taking into account all the angles.

The threat to Indigenous languages in Canada is serious. There are at least fifty different First Nations languages in Canada, belonging to eleven different language families. Indigenous languages are directly linked to traditional knowledge, traditional territories, collective identities, cultures, customs and traditions, personal identity, and personal well-being.

Fred Metallic cited from Marie Battiste, Editor Living Treaties Cape Breton University Press 2016 p. 47

The development of language programs in Wabanaki communities is supporting a resurgence of the language. There are immersion programs in schools and both online courses and university programs are being developed. Nevertheless, language preservation remains a challenge. One of the organizations attempting to make a difference is the Mi’kmaq–Wolastoqey Centre at the University of New Brunswick, which you can read about by following the link below the following illustration. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action, Nos. 13-17 acknowledged the importance of preserving and teaching Indigenous languages. Still, to date no Canadian court has ruled on whether the federal, provincial, or territorial governments have an obligation to provide greater funding or services for Indigenous languages. This is about to change.

In New Brunswick, bilingualism is promoted to serve both Anglophone and Francophone business endeavours, yet Wabanaki languages are viewed as languages of the past and of no practical use in business endeavours at the provincial level. Wabanaki economic success thus ends up depending on competency in either English or French, and Wabanaki languages are therefore marginalized.