Student Learning

I will be able:

- To roleplay an important historical event (Activity 1)

- To determine whether or not a treaty is fair and whether or not it can be signed in perpetuity (Activity 1)

- To use compare and contrast in reporting (Activity 2)

- To understand the significance and the political power of giving and taking land and food (Activity 2)

- To complete a case study of Kingsclear, looking at how the community changed over 150 years by making a graph, listing consequences, creating a timeline and illustrating variables in order to come to some conclusions (Activity 3)

A reserve being different to a grant, the Indian still has good title to any throughout the province, but unfortunately these lands have not been selected with due caution by those appointed to perform that duty. They are chiefly barren, and spots removed from the seacoast. Many portions of these reserves have also the white man as occupants, and although I am making efforts to force them off, I am met with a passive resistance from the squatter that will require all the vigour of this government.

William Charnley, Indian Agent, to Joseph Howe, 4 March 1854. In Legislative Assembly of Nova Scotia Journals. 1854, Appendix 26:211-212

Examine the composition of the monument.

This lesson is intended to show how over time, the British colonial government implemented a land policy that ignored any individual rights the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqewiyik and Peskatomuhkati (Passamaquoddy) had to their land. The Wabanaki were restricted to living in specific locations, within boundaries that were set by the colonizers. These were called reserves. As you explain this to your students, have them answer the following questions throughout the lesson:

- How could representatives from the colonial government and then the Canadian and provincial governments ‘give’ the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqewiyik and Peskatomuhkati (Passamaquoddy) their own land?

- Why did Indigenous people and the government think it best to keep them separate from non-Indigenous communities?

- How would a community on reserve have been different from the community before Europeans arrived (as described in Lesson A)? In what ways would it be the same? Think about:

- the boundaries in the community

- finding or collecting of food

- where people live in each season

- travelling to other Wabanaki communities

- How would men’s and women’s work have changed on reserve?

- Do you understand why Indigenous people of New Brunswick have the legal right to claim land rights?

As the questions are discussed, make a chart of your class’s opinions. (A key to the pronunciation of river and place names is provided immediately after the proper name in brackets.)

Reserves were created in several different ways and for various reasons. Before Confederation, colonial administrators established reserves to eliminate the nomadic lifestyles of Indigenous people. This lifestyle was not the result of homelessness, as the government perceived it. It was because Wabanaki homeland was vast and survival from the natural world depended on the traditional lifestyle of living in harmony with all of creation. Reserves were also established through treaties by ‘grants’ from the Crown, or through special arrangements with Indigenous individuals or groups. Small parcels of land were legislated and approved to make a home for the restless, homeless Wabanaki. Following is a short history about how reserves were developed in New Brunswick.

1778 – The government decided that it needed to determine the limits of Mi’kmaq villages all along the coast because of the arrival of new Loyalist settlers after the American War of Independence. Also, Acadians who either escaped the Deportation in 1755 or somehow returned were now making settlements on coastal rivers that drained into Northumberland Strait.

Small groups of Mi’kmaq also inhabited these same rivers at Aboujagane, Shediac and Cocagne. Further up the coast, the Mi’kmaq had villages along the Bouctouche River (Puktusk), Richibucto (Elsipogtoq (L’sipuktuk)), and Miramichi Rivers and at the mouth of the Tabusintac, Burnt Church and Pokemouche Rivers.

1779 – A move towards defining a land policy and ultimately a reserve was started when the British entered into a Treaty with the Mi’kmaq from Cape Tormentine to the Bay of Chaleur (at that time still part of Nova Scotia) in 1779. It started with this phrase:

Whereas, in May and July, last, a number of Indians at the instigation of the King’s disaffected subjects, did plunder and rob William John Cort and several others of the English Inhabitants at Miramichy of the principal part of their effects, in which transaction, we the undersigned Indians had no conscience, but nevertheless do blame ourselves, for not having exerted our abilities more effectually than we did to prevent it. Being now greatly distressed, and at a loss for the necessary supplies to keep us from the inclemency of the approaching Winter, and to enable us to subsist our families[.]

Among the conditions in this treaty were:

THAT, we will at the hazard of our lives defend and protect to the utmost of our power, the Traders and Inhabitants and their merchandize and effects, who are, or may be settled on the Rivers, Bays, and Sea Coasts against all the Enemies of His Majesty, King George, whether French, Rebels or Indians

THAT, the said Indians and their Constituents, shall remain in the Districts before mentioned, quiet and free from any molestation of any of His Majesty’s troops, or other of his good Subjects in their hunting and fishing.

As a result of signing this treaty, these Mi’kmaq, except the twelve that had been taken hostage, were given food instead of being taken as hostages themselves.

1783 – Following the loss of the British in the American War of Independence in September 1783, another major blow was delivered to the Mi’kmaq when the British made temporary land grants to them of pieces of their own land, on which the British expected the Mi’kmaq to stay. The lands were of poor quality and did nothing to help the Wabanaki to survive. The Wabanaki had limited understanding of the British concept of owning land. The British meanwhile had no understanding of collective stewardship of land versus “ownership”. Therefore, these land grants were soon encroached upon by unscrupulous newcomers.

1783 – The Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqewiyik shared a common understanding that land had been reserved for them by the Crown and in perpetuity. They went back to the Treaties of Peace and Friendship of 1760-61, when they had pledged their allegiance to King George III, and the 1783 license of occupation given to John Julian along two branches of the Miramichi (discussed here in Activity 1). Their expectation was, in the words of John Gonishe, Chief of Esgenoopetitj (Skno’pitijk) (Burnt Church) to “leave lands as it was given to them at first by His Majesty King George III as they were Aborigines of this land and born here on this ground.”

1811 – The government had set aside about 60,000 acres (243 km2) for Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqewiyik. Other than issuing orders through the Royal Gazette (printed in Britain and not usually distributed widely) forbidding anyone from occupying reserve lands, the government took no action against squatters. When it became obvious that squatters were seizing land, the government simply reduced the size of the land set aside for the Indigenous people. Along the Richibucto (Elsipogtoq (L’sipuktuk)), Puktusk (Puktusk) Bouctouche, and Oqpi’kanjik (Oqpi’kanjik) Eel River Bar Rivers, for example, the land was reduced to one tenth its original size.

On this issue, the first petitions were from both Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqewiyik and new settlers. The Wabanaki petitions stated their opposition to the selling of reserve lands to squatters. For example, Chief Paul Tenans petitioned for a survey of the Richibucto Reserve (Elsipogtog (L’sipuktuk)) to protect it against trespassers, to which the government gave its approval. Immediately following, the white population expressed frustration in a petition claiming that settlers from England were heading to the United States because they could not obtain land. The petitioners felt the loss of these possible settlers when ‘they see the land cloaked under the names of these poor infatuated [i.e., foolish] Indians who derive no benefits’. Squatting, however, continued.

1844 – The “Act to Regulate the Management and Disposal of the Indian Reserves” was passed by the New Brunswick legislature. The government now had the authority to auction reserve lands, regardless of any opposition from Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqewiyik who had been occupying this land for generations. The government would sell, by private auction, various lots of reserve lands occupied by squatters, along with other reserve lands which could then be opened to settlement by non-Indigenous people. The money raised by sales would be used to create an Indian Fund for their permanent betterment. However, the Act failed on both counts. The squatters, with a few exceptions, refused to purchase the land they illegally occupied. As a result, the Indian Fund never received any funds collected, so the Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqewiyik who stayed on reserve lands received no financial benefit from the sale of land and lost the lands occupied by squatters anyway.

1848 – Seventeen chiefs assembled in council at Burnt Church (Esgenoopetitj (Skno’pitijk)) to plead with the government not to sell any of their land. They prepared a petition for government that said their people were fast fading away and “the Reserves of land in different sections of the Country reserved for the use of the tribe by His Late Majesty King George III is the only source left to them in for a scanty subsistence in their helplessness. And which lands they cling to with the utmost tenacity as hallowed to them by the graves of their ancestors and from which they never wish to be parted in life and from a resting place for their bones in death.”

Hypothesize why John Francis would be so dressed up.

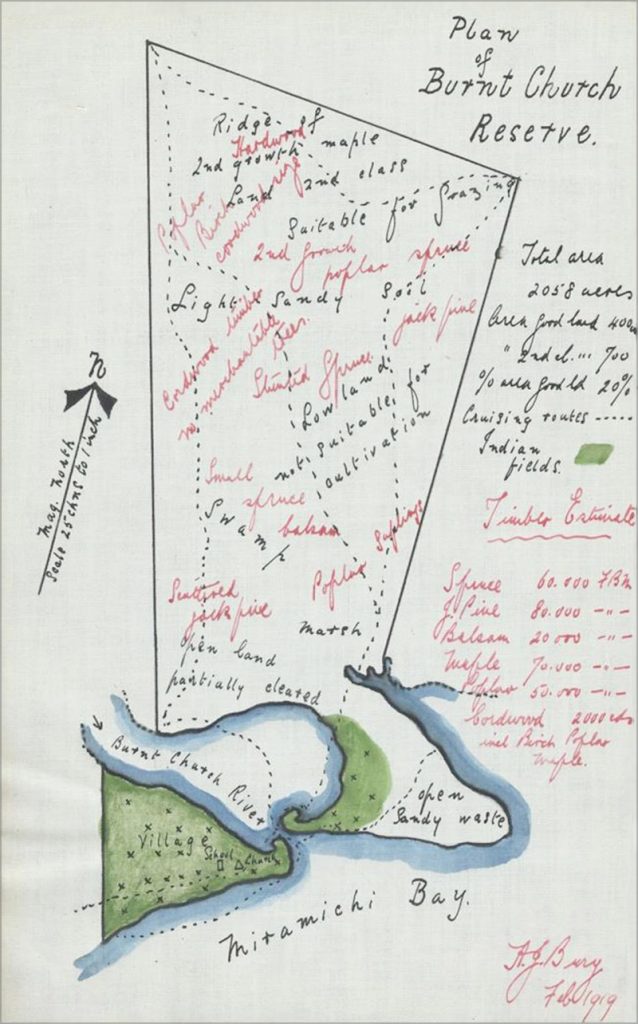

How much of this land is usable?

As an example, after the Act passed, the Wolastoqewiyik in Tobique (Neqotkuk) expressed major resistance to selling reserve lands. They argued that the land had been donated by the British government for their benefit. Tobique (Neqotkuk) was on the largest land settlement of any in New Brunswick. The government felt that the location of the Tobique (Neqotkuk) community was detrimental to development and felt that 120 immigrant families could be settled on this property. Over the course of 40 years, much of the original land grant to Tobique (Neqotkuk) was sold off.

In the 1950s, New Brunswick Power constructed two dams on Tobique (Neqotkuk) land, saying that there would be no interference with the salmon fishery. This was of special concern to the Tobique First Nation (Neqotkuk) because the fishery was important to its economy. By the time the dam on the mouth of the Tobique River was completed, the fishery had been destroyed. Power lines and roads ran over the reserve with little concern for the environment.

1849-1867 – In all, twenty thousand acres (81 km2) of reserve land in New Brunswick was put up for auction. There was no recognition in any of these transactions that the New Brunswick government acknowledged the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and its commitment to preserving Indigenous lands. As Chief Patricia Bernard of the Madawaska Maliseet First Nation puts it now: “The 1844 Act and its purpose to eliminate our homeland demonstrate not only the thinking of the time, but also how some non-Aboriginal leaders saw how this was unfair to Indigenous people in the province. In a time when settlement of the colony was vital to many politicians, there were some who understood that this land was never sold, nor ceded, nor obtained by conquest, and that the ‘Indians were the rightful possessors and Lords of the soil’.”

1940s – Throughout this time, the role and power of the Indian Agent on reserves became paramount through all the modifications and reconfiguring of reserves. This occurred without consultation with Wabanaki. This continued into the 1940s, when Canada established a policy for the removal of Mi’kmaq from their lands under a centralization policy that would relocate them onto three overpopulated and under-resourced reserves, Eskasoni and Shubenacadie in Nova Scotia and Big Cove (Elsipogtog (L’sipuktuk)) in New Brunswick.

The Wolastoqey communities were also affected. Had it not been for the centralization project that aimed to relocate Wolastoqey communities from other reserves to Kingsclear (Wolastoqey community) the school in that reserve would have ultimately been closed. It was primarily to keep its school that Kingsclear became the only community to endorse the centralization plan, while others, including St. Mary’s, Oromocto and Woodstock, vociferously opposed it. In the end, nine families from Oromocto were deceived into moving to Kingsclear (Wolastoqey community), with the promise of new houses, gardens, and farm animals. In spite of the resistance to this plan, smaller reserves were created, still with the same band council management scheme controlled by Indian Agents. This did nothing to reduce high levels of unemployment and social assistance.