Student Learning

I will be able:

- To apply the tenets of the Royal Proclamation of 1763 through role-playing a contemporary set of improvisations (Activity 1)

- To identify the levels of government that are responsible for different Wabanaki news events (Activity 2)

When Prince Arthur visited Nova Scotia in 1869, he was taken hunting near Caledonia. His Micmac guides were John Williams, Louis Noel, and old Peter Joe Cope with John Jadis, acting as camp boy. The Prince was accompanied into the woods by officers in dress swords, and a band. “Who in hell is going to kill moose with this noise going on?” said old Peter Cope. They were in the woods for three weeks and didn’t kill as much as a rabbit.

Jeremiah Bartlett Alexis (alias Jerry Lonecloud) to Henry Piers, 1 February 1926. Nova Scotia Museum Printed Matter File

This lesson raises concepts and ideas about the Wabanaki relationship with government that may appear difficult for Grade 5 students. The intent here is to provide background for teachers that will help them understand the basis behind some of the recent government decisions. The sections on the Indian Act in the Grade 5 textbook (pp. 108-112) provide further details about some of the sophisticated approaches to decision-making that the Wabanaki had in place through Mi’kmaw, Passamaquoddy and Wolastoqey Councils at all levels, long before the arrival of Europeans. In the textbook, lesson plans on consensus making and Wabanaki governance have also been provided. Given this elaborate decision-making structure, developed by the Wabanaki peoples throughout their history, it is difficult to understand why the federal government felt the need to impose the paternalistic structure of the Indian Act. The Indian Act outlawed Wabanaki forms of government and imposed the Chief and Council system.

This lesson examines the impact of two legal acts that have endured for a long time and their implications for the Grand Councils and the Wabanaki Nations.

Collectively, many Wabanaki people see their relationship to Canada as Nation-to-Nation. With that relationship comes certain obligations:

- Protection of the environment, which, in Wabanaki terms, includes respect for all the ancestors who came before the living and for all the generations to follow. This is referred to as ‘blood memory’ and refers to ‘Those who went before us and those yet to be born.’

- Living together in mutual understanding, respect and prosperity. For example, Land Acknowledgements highlight the historical fact that New Brunswick sits on the unceded and unsurrendered traditional territory of the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqewiyik and Peskotomuhkati. However, some Wabanaki believe a public land acknowledgement does not indicate that there is joint responsibility for caring for the land. Likewise, these acknowledgements do not describe how the land was illegally transferred and how the Wabanaki were removed from it.

- Understanding and committing to the spirit and intent of the Peace and Friendship Treaties

- Holding the sovereign right to Wabanaki law as well as Canadian law. The two-tiered system of (federal) Canadian law requires that a law must be passed first by the House of Commons and then by the Senate. Once approved by the Senate, Canadian law becomes enshrined and difficult to change. This process presents a challenge for change: for Wabanaki law to be respected, both houses would have to pass a Self-Determination Act recognizing Indigenous laws in general and Wabanaki law here in the Atlantic Provinces.

- Mutual equality, justice and protection for all peoples.

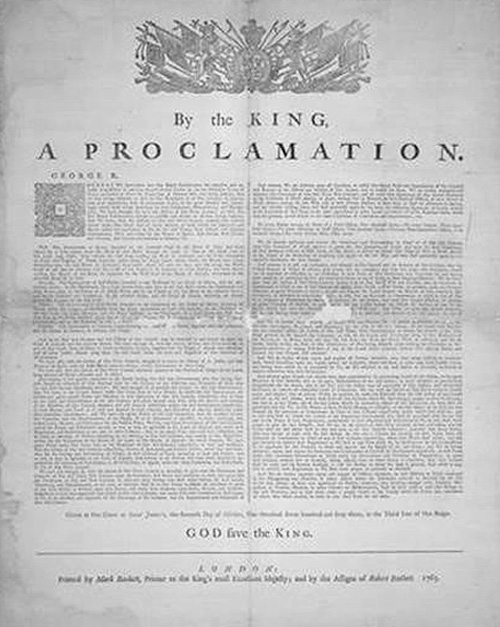

Royal Proclamation of 1763

Before the Proclamation, the Treaty Commissioners made a formal statement: “We are directed by the government to tell you that the English have no design to take your country or any of your lands from you: or to deprive you of any of your just Rights or Privileges” (November 1720, English Treaty Commissioners).

On October 7, 1763, King George III issued a Royal Proclamation. It was intended to keep Indigenous people as allies during periods of war and also keep them as trading partners. It did this by recognizing Indigenous hunting territories and providing for their protection by establishing “hunting grounds” safeguarded against further encroachment. It acknowledged that Treaties reserved land for Indigenous people, and it asserted that all Treaties made thus far had to be acknowledged.

Indigenous people believe that the Royal Proclamation recognizes them as owners of their traditional territories. This is reflected in the Royal Proclamation’s key words, “ … any lands that had not been ceded to or purchased by Us as aforesaid, are reserved to the said Indians.” Finally, it set out guidelines for European settlement of Indigenous territories. However, it was to be a futile attempt to preserve the lands remaining to Indigenous peoples and to some degree their cultures.

Within each Wabanaki Nation there were permanent villages and hunting territories assigned to different clans. When the clans went to their hunting territories, they also harvested medicines, maple syrup and materials for lodges and birchbark canoes. Hunting territories were more than areas for hunting game, they also provided additional resources for survival.

WHEREAS, it is just and reasonable, and essential to our interest, and the security of the Colonies, that the several Nations or Tribes of Indians with whom We are connected, and who live under our protection, should not be molested or disturbed in the Possession of such Parts of Our Dominions and Territories, as not having been ceded to or purchased by us, are reserved to Them or any of them, as their Hunting Grounds.

No European settlement, occupation or infringement would be permitted on these “hunting grounds” without the consent of the Crown. The Royal Proclamation also established a ‘Trust Relationship’ between the Crown and Indigenous people by stating that only the Crown could ‘purchase’ the land from First Nations. Finally, it specified that many new colonists were guilty of land theft. However, this Proclamation did not stop it from continuing. The British Crown and later Canada ignored the Proclamation.

AND, We do further strictly enjoin and require all Persons whatever, who have willfully or inadvertently seated themselves upon any Lands within the countries above described, or upon any other Lands, which not having been ceded to or purchased by Us, are still reserved to the said Indians as aforesaid, forthwith to remove themselves from such Settlements.

Indian Act

The British North America Act, 1867, which created Canada, gave the federal government the constitutional responsibility and jurisdiction over “Indians and lands reserved for Indians.” The First Nations peoples were not invited to be part of these discussions, nor were they consulted when the federal government became responsible for them. Neither did they know they would become wards of the government.

The Indian Act of 1876 is a Canadian federal law that governs matters related to Indigenous (Indian) status, bands, and reserves (now called communities). Paternalistic and invasive, it places control of Indigenous people in the hands of the Department of Indian Affairs; its primary goal is to assimilate Aboriginal people into mainstream (i.e., settler) society. It authorizes the Canadian government to regulate and administer the affairs and the day-to-day lives of registered Indigenous people and their reserves, to exercise overarching political control over Indigenous nations by imposing the Chief and Council system as their system of governance, and even to control communities’ cultural and traditional practices. The Act determines land use and the criteria for who qualifies as “Indian” under its regulations, even though Indigenous people have their own terms for self-identification.

Although it has undergone many changes since 1876, it still retains its original purpose. Many people believe it reflects the assimilationist policies that intended to end the cultural, social, political, and economic distinctiveness of Indigenous people. This belief is hardly surprising when one reflects that for a long time, the French name for the Indian Act was the ‘Act Concerning the Savages’, while the Department of Indian Affairs was called the ‘Department for the Savages’ Affairs’ in French until 1922.

The great aim of our legislation has been to do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian People in all respects with the other inhabitants of the Dominion as speedily as they are fit to change

Sir John A. Macdonald, 1887

Under the Indian Act, equality never emerged. The Canadian government assumed control of First Nations’ governance, economy, religion, land, education, and personal lives. There was perpetual dominance by the Canadian government. Indigenous people were marginalized. For example, in the beginning, it was enough for an Indigenous person to attend university to have their Indigenous status denied (because going to university was a sign of being “advanced” and therefore having assimilated into settler society). Status Indians became citizens of Canada in 1956 but did not have the right to vote until 1960 and were not allowed to travel away from most First Nation communities.

Is the Royal Proclamation still valid?

Many Indigenous people believe that the Royal Proclamation was a first step in acknowledging Indigenous Rights. Although the Wabanaki had already signed a number of treaties (e.g., Treaties of 1725, 1749, 1752, 1760-61, etc.), other Indigenous groups saw this Proclamation as the foundation for the process of establishing treaties. The Proclamation gives evidence of Indigenous sovereignty and their rights to land and resources. However, the Proclamation presents a British point of view without Indigenous involvement, and clearly sets up a monopoly over Indigenous lands by the British Crown. Today it is often used in legal arguments and in disputes with the Crown’s interpretation of the Treaties.

The Royal Proclamation is enshrined in Section 25 of the Constitution Act. This section of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees that nothing can extinguish Aboriginal (Indigenous) Rights as outlined in the Proclamation. Despite this, Indigenous people still have to prove their existing title to the land through legal disputes.

Indian Act and Policy

Today, through the Indian Act, the Federal Government does the following:

- still holds all lands in trust for Indigenous people

- still determines status and membership

- still determines where children go to school

- still manages hundreds of millions of trust money in the name of Indigenous people

- still manages First Nations’ elections

- still controls property rights and inheritance

- still manages lands/resources

- still aimed at integration and breaking tribal bonds

- still fighting equality for Indigenous youth

- still preventing expedited land claims

So why not abolish the Indian Act?

The Indian Act still remains a controversial piece of legislation. The Assembly of First Nations calls it a form of apartheid. Amnesty International, the United Nations, and the Canadian Human Rights Commission call it legislated human rights abuse.

Most First Nations want the Indian Act repealed and replaced with a legislative initiative for Indigenous self-government — not amended, but repealed. However, some First Nations are satisfied with remaining under the Indian Act because it still affirms the unique constitutional relationship Indigenous people have with Canada. If there are to be any further changes to the Act, Indigenous governments all agree that they will have to be active participants in making those legislative changes. Responsibilities must be agreed to by all parties.

Mi’kmaw, Passamaquoddy and Wolastoqey Governance

Band councils

Some colonial terms such as Indian band or band are no longer acceptable terms for First Nation peoples. A First Nation is the basic unit of government as defined in the Indian Act. Each First Nation is typically represented by a band council chaired by an elected chief, and sometimes also a hereditary chief. Membership in a band is controlled in one of two ways. First, for most bands, membership is obtained by becoming listed on the Indian Register maintained by the federal government. The other way is to become accepted as a member of a band by one of the First Nations. This means that you may be a member of a First Nation but not be recognized as a Status Indian, as defined by the Federal Government. As of 2013, there were 253 First Nations in Canada that had their own membership criteria.

First Nations can be united into larger regional groupings called tribal councils. Another emerging type of organization is the chiefs’ councils, such as the Wolastoqey Nation (below). First Nations also typically belong to one or more kinds of broader councils or similar organizations that may include representation from other provinces and states, such as the Wabanaki Confederacy or the Mi’kmaq Grand Council (Santé Mawiómi). These were discussed in some detail in Grade 4. They also have representation on the pan-Canadian Assembly of First Nations (formerly called the Native Indian Brotherhood), chaired by an elected leader, in which each First Nation has one vote. First Nations are, to an extent, the governing body for their communities. Many First Nations also have large Indigenous urban populations whom the First Nation government also represents, and they may also deal with non-members who live in First Nation communities or work for the First Nation.

Karl Hele (a leading authority on the Indian Act) says:

According to the Government of Canada, only ‘Indians’ that are ‘Indians’ are those recognized by the Gov’t of Canada under the terms of the Indian Act. The gov’t definition of Indian is complicated and convoluted.

‘Indians’ while having a say concerning band membership do not have the right to confer or deny status.

None of the status rules actually follow ‘Indian’ traditions or concerns.

Only status Indians and ‘Treaty Indians’ have rights under Section 35 of the Constitution and in the Indian Act.

Collection of Jason Barnaby

Wolastoqey Nation in New Brunswick

The Wolastoqey Nation is one example of a chief’s council: Originally referred to as the Maliseet Nation in New Brunswick (MNNB), the Wolastoqey Nation in New Brunswick (MNNB) received its Certificate of Incorporation in April 2017 and changed its name to Wolastoqey Nation in New Brunswick (WNNB) in July 2017. WNNB consists of Madawaska Matawaskiyak Maliseet First Nation, Tobique First Nation (Neqotkuk), Kingsclear First Nation, St. Mary’s First Nation and Oromocto First Nation. This organization provides technical advice to Wolastoqey leadership and Resource Development Consultation Coordinators (RDCCs) for matters that relate to the implementation and exercise of constitutionally protected Wolastoqey rights. WNNB aspires to protect and promote traditional lands, ceremonies, cultural practices, and language. Some of the projects presently being worked on include forestry, strategic rights plan, fisheries, climate change, environmental reviews and traditional land use studies.

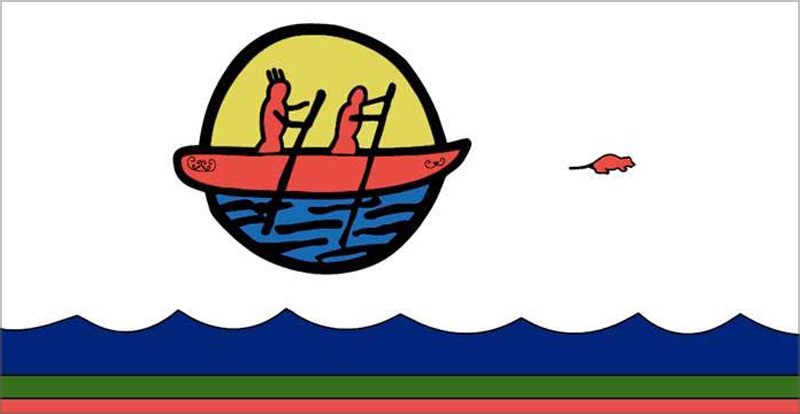

Wolastoqey Motewekon Nation Flag

Wolastoqey Nation of New Brunswick Logo and Flag Description

Explanation: We are wrapped with the Wabanaki Sky – We are the people of the dawn. We gather around the centre of the fire. All our six Wolastoqey Nations stand with Unity. Together we keep the fire lit and our wigwam where we gather. Together we honour our traditions, our stories and our teachings and the importance of our council fires. The earth under our feet represents our ancestors who guide us as leaders and carriers of knowledge. Representing we all carry the bundle of medicine that helps to move our culture forward and weave these teachings into the life we live in today. The double curve wraps the sky – both arms of the double curve hold colours of the wampum symbolizing our treaties and our 7 generations before us and our 7 generations of leaders to come. Below, the river that connects all our 6 nations, representing we are Wolastoqewiyik (The people of the beautiful bountiful river).

See how many of these elements you can identify in this flag.

Wolastoqey Grand Council

Explanation: The Wolastoqey Grand Council, the original governing body of the Wolastoqewiyik before the Chief and Council system was created by the Indian Act, adopted this symbol to print on a flag approximately ten years ago. An historical document found in the archives explains who the Wolastoqewiyik were. The people were formerly known as Kiwhosuwi-skicinuwok (Muskrat People) before being known as Wolastoqewiyik. Kiwhos (muskrat) is their tutem (totem), hence the male and female following Kiwhos (muskrat) poling in their canoe. Kiwhos (muskrat) provided food and clothing for the Wolastoqewiyik, as well as guiding them to find the most valuable medicine, Kiwhosuwasq. This historical symbol illustrates in detail who the Wolastoqewiyik are as a People. The bottom red line portrays the ancestors who are deeply rooted in the homeland, Wolastokuk. The green line represents all vegetation trees, grass, food and medicine; all that sustains life. The blue is water: brooks, streams, rivers, lakes and oceans. Water nourishes all creation to help food and medicine grow which in return balances life. The yellow is the sun that shines upon earth to help food & medicine grow and gives warmth and light. The sun evaporates the water to form clouds that return the water to nurture the earth. The sun reminds Wolastoqewiyik that they are a part of the Wabanaki Confederacy, the People of the Dawn.

Activity Profile

Declaration to rename the Wolastoq

On June 23, 2018, Wolastoqewiyik – People of the Beautiful and Bountiful River – and allies stood shoulder-to-shoulder in ceremony to reclaim the river’s beautiful and bountiful name. Hereditary chief Ron Tremblay proclaimed:

In 1604, when Champlain landed on the shores of Passamaquoddy Homeland and eventually voyaged to Wolastokuk, our Beautiful and Bountiful Homeland, he renamed Wolastoq, our Beautiful and Bountiful River to the name Saint Jean after Saint Jean the Baptist. By doing so, Champlain was declaring that since Wolastoqewiyik who occupied the lands and rivers were not Christian people he had the right to rename and take the land and rivers from Wolastoqewiyik. This in return made Wolastoqewiyik virtually invisible in their own land.

But the land was not empty, Wolastoqewiyik were here then; and we are still here now. Later, the British settlers who colonized our Wolastokuk (Wolastoq Homeland) changed the spelling from French to English, Saint Jean to St. John.

During all that time, our Wolastoqey ancestors were never consulted about whether our river could be renamed. Saint John the Baptist had no relationship with our people then, and very little relationship with our people today.

The response from government officials was that this would be too difficult, as it would involve not only New Brunswick but also Quebec and Maine, a state in the United States. Wolastoq (the St. John River) flows through all three of these geographic areas.

The Wolastoqey Grand Council, a traditional body not formally recognized under the Indian Act, raised the idea in both 2017 and 2018, saying it would be consistent with the goals of the National Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

Grand Council Mi’kmawey Mawio’mi

The Grand Council (Santé Mawiómi or Mi’kmawey Mawio’mi) was the traditional senior level of government for the Mi’kmaq based in present-day Canada, until the passage of the Indian Act in 1876 required elected governments. After the Indian Act, the Grand Council adopted a more spiritual function. The Grand Chief was a title given to one of the district chiefs, who was usually from the Mi’kmaq district of Unamáki (Cape Breton Island). This title was hereditary and usually was passed down to the Grand Chief’s eldest son. The Grand Council met on a small island in Cape Breton called Mniku. Today it is within the boundaries of Chapel Island First Nation or Potlotek. To this day, the Grand Council still meets at the Mniku to discuss current issues within the Mi’kmaq Nation.

The Mi’kmaq of Nova Scotia still meet at Mniku as they have done for many years. In New Brunswick, the Mi’kmaq come together in Esgenoopetitj (Skno’pitijk) and also celebrate the feast of St. Anne, their patron saint. Esgenoopetitj (Skno’pitijk) was known as the meeting place for the Mi’kmaq before the government made gatherings against the law. Mi’kmaq would hold meetings on social and political issues at this time. Weddings were also celebrated; traditional courts were held; there were many other social issues discussed.

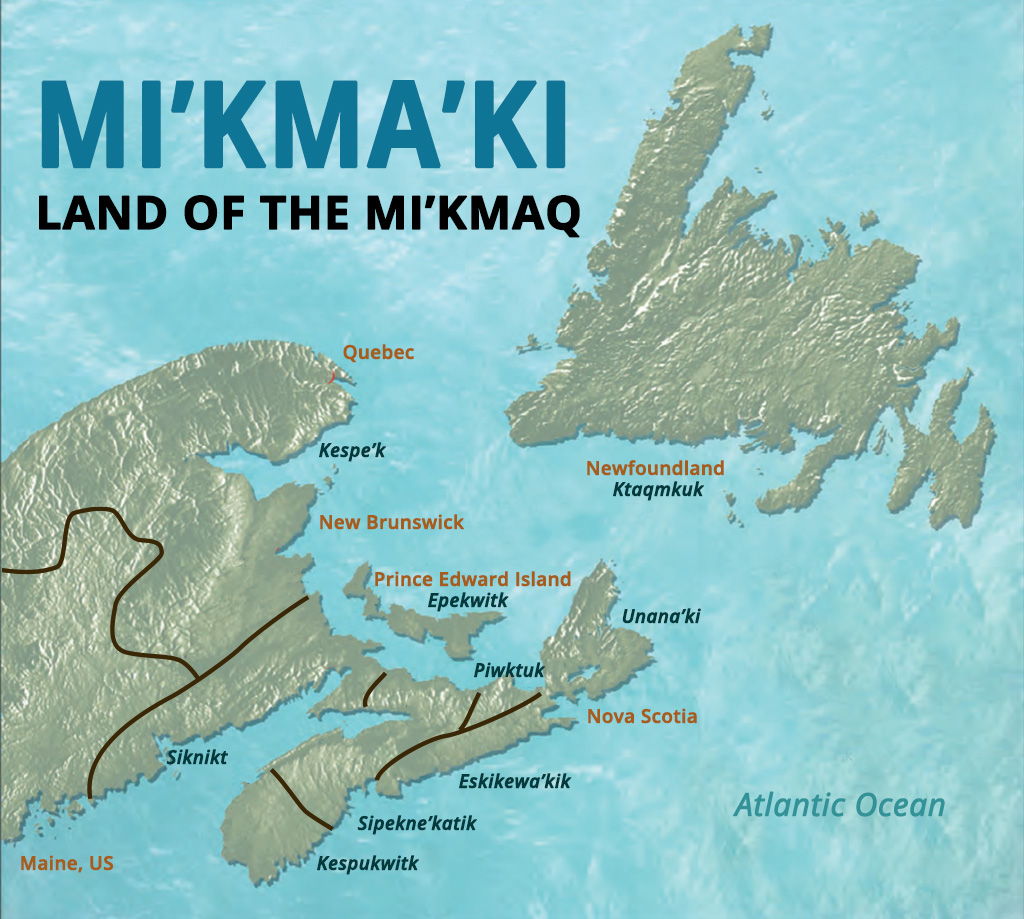

Traditionally, the Mi’kmaq also have seven distinct districts. Their names are:

- Kespukwitk (Land Ends) – the counties of Queens, Shelburne, Yarmouth, Digby and Annapolis, Nova Scotia

- Sipekne’katik (Wild potato area) – the counties of Halifax, Lunenburg, Kings, Hants and Colchester, Nova Scotia

- Eskikewa’kik (Skin Dressers Territory) – the area stretching from Guysborough County to Halifax County, Nova Scotia

- Unama’kik (Land of Fog) – Cape Breton Island and Ktaqmkuk (Land across the water) – island of Newfoundland

- Epekwitk (Lying in the water) – Prince Edward Island

- Piwktuk (The Explosive Place) – Pictou County, Nova Scotia

- Siknikt (Drainage area) – including Cumberland County in Nova Scotia, and the counties of Westmorland, Albert, Kent, Saint John, Kings and Queens, in New Brunswick

- Kespek (Last Land) – the area of north-eastern New Brunswick, north of the Richibucto River and the southern part of the Gaspé Peninsula in Québec

These districts were related to the ocean and were comprised of inland sections that followed drainage systems and principal river systems, forming natural boundaries. The feast of St. Anne has been the occasion for meetings for the Mi’kmaw Grand Council for more than 250 years, dating back to an 18th-century treaty-making period between the British and the Mi’kmaq. This feast was celebrated by Mi’kmaq who had converted to the Catholic religion. Some rejected the Catholic religion and maintained their traditional spirituality and belief system.

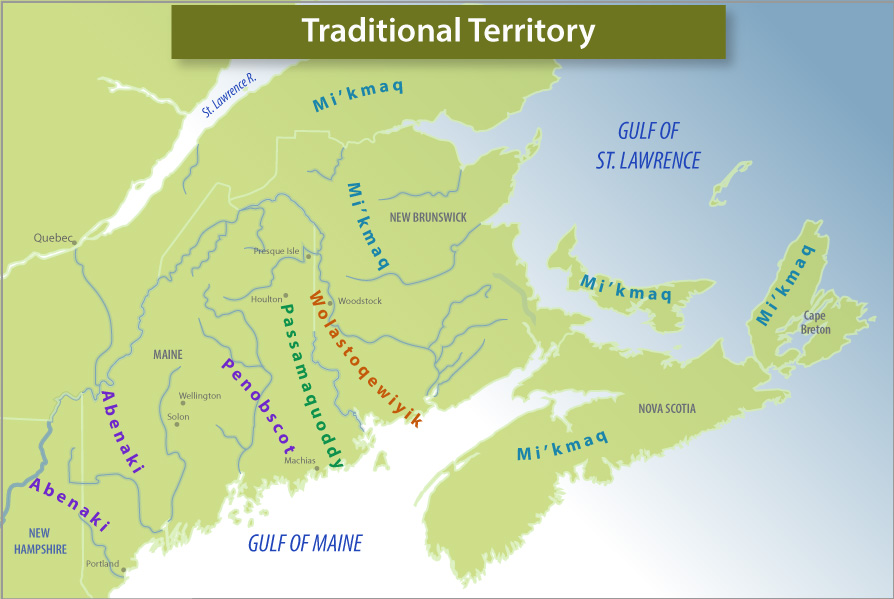

Waponahkiyik (Wabanaki) Confederacy

In Grade 4, students also learned about the Waponahkiyik (Wabanaki) Confederacy, which had been formed by the north-eastern First Nations (Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqewiyik, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot and Abenaki) for the purpose of providing mutual protection from aggression by other hostile nations. Today, as the Confederacy, it spans two countries as well as five Wabanaki Nations. Its mandate continues to discuss topics that bridge borders and unite peoples. One of the most important topics they have addressed recently is the truth about the harmful way the state of Maine treated Indigenous children in the past. For more information, see: https://static1.squarespace.com/static/56a8c7b05a5668f743c485b2/t/5a67a85ac830250414b03b8a/1516742748154/Headline+News+Identity.docx.pdf.

“Many truth commissions around the world have set out to incorporate the voice of Indigenous people who have suffered human rights abuses at the hands of government and other political groups. Most of these official truth commissions, however, have also had a nation-building objective, at least in the sense of legitimizing or re-legitimizing the government in power, and some Indigenous rights activists are uncomfortable participating in them for that reason.”

Esther Attean and Jill Williams, Homemade Justice, Cultural Survival Quarterly March 2011

In the past, during the treaty-making process, it was never altogether clear to the British who should be invited to sign the Treaty. However, for the Wabanaki, it was important that the Treaties be ratified from generation to generation. The Waponahkiyik (Wabanaki) Confederacy was a means whereby important agreements/treaties were sent to all the participating nations.

Today, among Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqewyik and Passamaquoddy (Peskotumuhkati in Canada) there are often extended discussions to accommodate the inclusion of all voices, including that of Elders and Clan Mothers. Typically, Clan Mothers are in charge of appointing chiefs and passing on cultural knowledge in decision-making. It is a traditional role held by an Elder matriarch. In these open societies, everyone’s voice matters. Wabanaki Nations continue to be committed to deciding things collectively and by consensus. This means it can take weeks or months to make a final decision once everyone has had their opinion considered. This presents real challenges today, when given situations often demand immediate responses, and has often led to protests because government has moved forward without true and comprehensive consultation.