Student Learning

I will be able:

- To identify stereotypes about Indigenous peoples and the harm they levy on First Nations people (Activity 1)

- To use the fishery dispute in Esgenoopetitj (Skno’pitijk) as an example to explore the ramifications of self-determination (Activity 3)

- To list the advantages and disadvantages of leading a protest (Activity 3)

- To judge for myself about what I believe to be right or wrong about the things that have happened. (Your judgement is your opinion. Opinions are not facts but how people feel about facts) (Activity 2 and 3)

- To be able to understand and articulate arguments in a court case involving Rights of Aboriginal people (Activity 2)

There are words I want to put on wings

Rita Joe (Joe and Choyce 2003, p. 95)

That when I am gone, someone will read

Maybe to create the emotions inside

And tell their own story, instill pride

Then their words will have wings

To create another thought, pretend

We are a chain linking together

To span a bridge where communication scatters.

The four activities in this lesson are designed to help students understand how modern-day interpretations of 18th century treaties have led to many court cases and differences of opinion between the Government of Canada and First Nations in New Brunswick, at both the individual and group level. They deal with stereotyping, the application of Indigenous hunting rights, a play which demonstrates the covenant nature of the treaties and how this protects the future of Wolastoqewiyik, and finally an example of a major controversy which arose from a lack of understanding by federal fishery officers of the fishing rights of the Mi’kmaq. As a reference, the Covenant Chain of Treaties, a short summary of some of the most impactful Treaties is attached and an animation is also provided. This was also included in the Grade 4 programme.

Postcard v.1910 New Brunswick Museum X14839

This lesson starts out with an activity on stereotyping. The postcard above is a good example. Inside a wigwam is what appears to be an Indigenous woman. She appears to be protected by what was formerly Canada’s flag — the Red Ensign. A second example is the word Indians, the word assigned to Indigenous Americans by Columbus, who thought he had arrived in the Indies (southeast Asia). This word has been the cause of many misunderstandings. Using this word does not in any way reflect the diversity of Indigenous peoples. Most people have never had the opportunity to meet Indigenous people and this has caused further misconceptions.

In the last lesson, students learned about the Indian Act and how Canada granted itself the legislative framework from which to both standardize and enforce Canada’s narrow view of Treaties. The Indian Act is a discriminatory approach to dealing with First Nations peoples. It was legislated to guide Canada’s relations with First Nations peoples by imposing restrictions on them to meet two main goals for the government: 1) to Europeanize the Indigenous peoples, and 2) to assimilate them into the mainstream society.

When First Nations protests did not subside, the federal government amended the Indian Act in 1927 to forbid First Nations from sharing their opinions publicly or organizing themselves politically. Consequently, the First Nations had very few ways to voice what they truly believed their treaties were made to convey. Resistance to this mounted and in 1951 the act was amended to again allow political organizing.

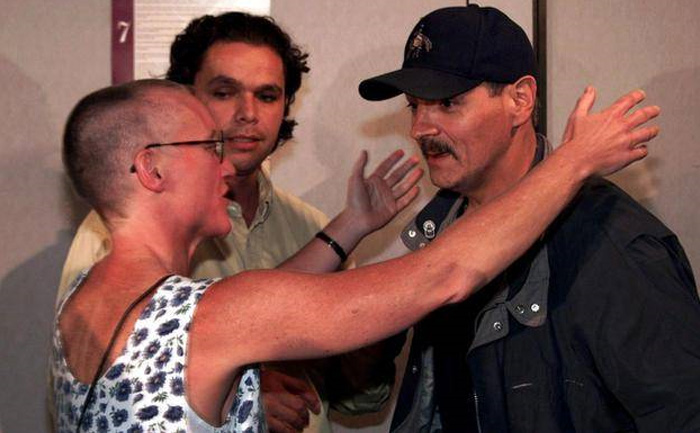

Through continued confrontations and court actions, the existence of Indigenous rights has been clearly and firmly established. Indigenous people have been consistently challenging the status quo to insist that these rights be recognized, affirmed, and protected. However, this process often leads to confrontation and sometimes violence. This lesson examines some of the sources of this confrontation — including discrimination and prejudice — by looking at the example of the lobster fishery in Esgenoopetitj (Skno’pitijk) in 2000. This case is based on the Marshall Decision.

The Marshall Decision

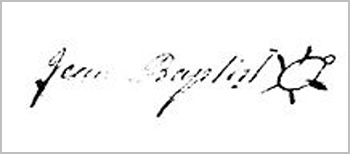

The Peace and Friendship Treaty of 1752, signed by Chief Jean-Baptiste Cope of Shubenacadie and Governor of Nova Scotia Peregrine Thomas Hopson, promised the Indigenous population hunting, fishing, and trading rights in exchange for peace.

It is agreed that the said Tribe of Indians shall not be hindered from, but have free liberty of Hunting & Fishing as usual: and that if they shall think a Truckhouse needful at the River Chibenaccadie or any other place of their resort, they shall have the same built and proper Merchandize lodged therein, to be Exchanged for what the Indians shall have to dispose of, and that in the meantime the said Indians shall have free liberty to bring for Sale to Halifax or any other Settlement within this Province, skins, feathers, fowl, fish or any other thing they shall have to sell, where they shall have liberty to dispose thereof to the best Advantage.

In 1993, Donald Marshall Jr. argued that the Treaty of 1752 gave him the right to fish commercially and be exempted from federal regulations. He caught 463 pounds (210 kilograms) of eels using a prohibited net in the off-season. He did not have a license to do so and he sold the eels. He was charged with four violations of federal fisheries regulations. After being arrested and after twice losing the court case within the Nova Scotia system, Donald Marshall Jr. appealed to the Supreme Court of Canada. (See also: https://ojen.ca/en/resource/landmark-case-aboriginal-treaty-rights-r-v-marshall).

In 1999 the Supreme Court of Canada ruled in favour of the rights of Indigenous people to fish and to be able to sell their fish under the Treaties signed in 1752 and again in 1760-61. The decision known as Marshall No. 2 states that “the treaty rights permit the Mi’kmaq community to work for a living through continuing access to fish and wildlife to trade for ‘necessaries.” (R. v. Marshall 1999b; para.4) After this decision, the people of Esgenoopetitj (Skno’pitijk) agreed to set up a food fishery. It became a major source of contention between the Federal Department of Fisheries, the licensed non-Indigenous fishers and the community of Esgenoopetitj (Skno’pitijk). During the conflict that followed, the community of Esgenoopetitj (Skno’pitijk) was supported by many other First Nations across the country. Video footage from the conflict shows a small boat with three Mi’kmaw fishermen aboard being run over twice by a large DFO boat, forcing the fishers into the water where they were picked up by police. See also: https://youtu.be/HsvG4KpFHOA.

Covenant Chain of Treaties

The Covenant Chain of Treaties is a group of interconnected treaties, whereby the British Crown and Waponahkiyik First Nations created a chain of related commitments to each other. There were other treaties and alliances signed before, during and after those listed here. These were selected because they figure prominently in recent cases that have been decided upon by the Supreme Court of Canada. You can find more information at the Atlantic Policy Congress website, http://www.apcfnc.ca/about-apc/treaties/.

1725/26/28 There were two similar treaties negotiated in Boston in 1725 by Governor Dummer. The first one was signed by four Penobscot representatives, but other groups were in attendance including the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqewiyik and Passamaquoddy (Peskotomuhkati) who attended the ratification. The first of these treaties was known as Governor Dummer’s Treaty and was ratified again by Waponahkiyik in what is now Maine. The second treaty is known as Mascarene’s Treaty since Paul Mascarene had been sent to negotiate a separate treaty for Nova Scotia. This treaty, between the British, Mi’kmaq and Wolastqewiyik (Maliseet) and Passamaquoddy (Peskotomuhkati) was then ratified by most of the Mi’kmaw and Wolastoqewiyik (Maliseet) and Passamaquoddy (Peskotomuhkati) villages at Annapolis Royal in 1726 and again in 1728. It was the first of what are now known as treaties of Peace and Friendship with the British Crown in the Maritime Provinces. What is important is that this Treaty known as Mascarene’s Treaty, consisted of two parts, one part containing Mi’kmaw, Passamaquoddy (Peskotomuhkati) and Wolastoqey promises, and another part containing English promises, including the most important promise to respect Indigenous hunting, fishing, and planting grounds.

1749 The Royal Commission of Inquiry into the legal rights of the Indigenous nations in North America said that: “Indians, though living amongst the King’s subjects in these countries, are a separate and distinct people from them, they are treated as such, they have a policy of their own, and they make peace and war with any nations of Indians when they think fit, without control from the English.”

1749 Treaty signed at Chebucto (Halifax) and ratified on the St. John River renewing the Treaty of 1725. Governor Edward Cornwallis, hoping to secure control over lands west of the Missaguash River (New Brunswick border), invited the two Indigenous nations to sign a new treaty to reconfirm loyalty to the Crown. However, most Mi’kmaq leaders refused to attend the 1749 peace talks in protest of the governor’s founding of Halifax that year. Increasing British military presence and settlement in the region threatened traditional Mi’kmaw villages, territories, and fishing and hunting grounds. Only the Chignecto Mi’kmaq joined the Wolastoqewiyik in signing the treaty. In the continuing campaign for Chignecto, Governor Cornwallis punished the Mi’kmaq who did not attend by offering a reward of ten guineas for the scalps of Mi’kmaw men, women, and children. The London Board of Trade disagreed with this “extermination” policy.

https://globalnews.ca/news/2682555/scrubbing-the-name-of-halifax-founder-edward-cornwallis-to-be-put-to-a-vote/

The statue of Edward Cornwallis stood in downtown Halifax until it was taken down in 2017. Why do you think this was done?

1752 The Treaty of 1752, signed by Jean-Baptiste Cope, described as the Chief Sachem of the Mi’kmaq inhabiting the eastern part of Nova Scotia, and Governor Hopson of Nova Scotia, made peace and promised hunting, fishing, and trading rights. It put an end to the skirmishes of 1749-52. “It is agreed that Indians shall not be hindered from but have free liberty of hunting and fishing as usual.” It also dealt with matters of justice: for disputes between Wabanaki and the British, the English civil justice system would prevail, and Wabanaki would receive the same treatment as the British. There are many instances of the Mi’kmaq stating that they had not agreed to this term.

1760 A new treaty was signed in Halifax by Mitchell Neptune, Passamaquoddy (Peskotomuhkati), and Ballomy Gloade, Wolastoqewiyik (Maliseet). There was no surrender of land and land was not ceded to the British. This treaty focused on renewing the old treaties of 1726 and 1749 and incorporating them into a new Peace and Friendship Treaty. The emphasis was on the trading of furs for European goods and was followed up by an agreement on trading. This Treaty was signed later in the year by delegates from Richibucto, la Hève (La Have), Schubenacadie, Pictou, Malagomich (Merigomish), Cape Breton, Shediac, Miramichi and Pokemouche.

1760-61 Treaties of Peace and Friendship were made by the Governor of Nova Scotia, Charles Lawrence, with the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqewiyik (Maliseet) and Passamaquoddy (Peskotomuhkati). These are the same treaties that were upheld and interpreted by the Supreme Court of Canada in the Donald Marshall Jr. case. They include the right to harvest fish, wildlife, wild fruit, and berries to support a moderate livelihood for the treaty beneficiaries. While the groups promised not to bother the British in their settlements, the Wabanaki did not cede or give up their land title and other rights.

1762 Triggered by Royal Instructions in 1761, Belcher’s Proclamation described the British intention to protect the just rights of the Mi’kmaq to their land “setting aside lands for Indians, incorporating the coastal areas from the Strait of Canso to the Bay of Chaleur for the special purpose of hunting, fowling, and fishing.”

Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton

1763 The Royal Proclamation of 1763 is a complicated document that reserved large areas of land in North America as Indian hunting grounds and set out a process for the cession and purchase of Indian lands. It is still seen as a foundational document in the relationship between First Nations peoples and the British Crown.

1776 The treaty of 1776, signed in Watertown, MA, USA, established relations with the newly created United States against the British. The Americans promised to approach their relationship with the Mi’kmaq in the manner of the French rather than the British. Oral tradition and wampum illustrate that this happened. Although there is no evidence that Wabanaki from Canada signed it, this is why Wabanaki in the Maritimes can still sign up for the United States military.

1778–1779 With the start of the American Revolution in 1775, the final treaty between the Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqewiyik and the British was signed over two years. In 1778, this treaty included Wolastoqey delegates from the St. John River area and Mi’kmaw representatives from Richibuctou (Richibucto), Miramichi and Chignecto. In 1779, the peace agreement included Mi’kmaq from Cape Tormentine to Baie de Chaleurs. It promised not to assist the Americans in the revolution and to follow their “hunting and fishing in a peaceable and quiet manner.” The military threat from the Mi’kmaq was diminished significantly by this treaty.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military_history_of_the_Mi%27kmaq_people#Halifax_Treaties

For Indigenous people, treaty-making operated on the principle of extended family. Treaties reflect three things: 1) interconnectedness 2) intergenerational and 3) interdependency. Therefore, a treaty is considered a sacred vow or Covenant. Treaty-making is part of a sacred order and every time a treaty is made it is adding to the order. As treaties build on each other, they add to and project the extended family and intergenerational life experience. As Fred Metallic, from Listuguj, says, ‘We are all brothers and sisters in Creation. Treaties are covenants to that order and guide us in our relationships.’ (Battiste, Marie Living Treaties 2016 p. 46) The British did not have this emphasis at all on treaties being intergenerational.

January 15, 1971 New Brunswick Archives P366. Why do you think the Metepenagiag (Metepna’kiaq) First Nation would be presenting a headdress to a Premier? What do you think they might be holding?

To reinforce the chain of treaties timeline, have the students complete the following animation.

Important note: Do not hesitate to click on “Pause” in the progress bar while looking at the animation, so you can observe more details in the pictures or the illustrations.