Student Learning

I will be able:

- To appreciate that what the Wabanaki leaders thought they were committing to in the original treaties was not what the British government had established (Activity 1 and 2)

- To identify some of the traits required of a leader who must enter into negotiation with present-day governments and compare them with my own (Activity 1)

- To write a biographical sketch of an Indigenous leader who has affected Treaty Rights in the province (Activity 2)

- To create a timeline showing contemporary leaders and their roles in determining Rights and Treaties (Activity 2)

The Abbé Mallaird (Maillard) being introduced, interpreted the treaty to the Chief…The Chief then laid the hatchet on the earth, and the same being buried the Indians went through the ceremony of washing the paint from their bodies, in token of hostilities being ended, and then partook of a repast set out for them on the ground, and the whole ceremony was concluded by all present drinking the King’s health …This ceremony is said to have been performed in the Governor’s garden.

Thomas Akins History of Halifax City 1973:64-66

By making treaties, the Eastern Nations sought to live in peaceful co-existence with those they had once viewed as welcome guests. I firmly believe that the Mi’kmaq would have never signed the Treaty of 1725, which portrayed them as servants paying homage to a lord and master, the English King, if they understood the meaning and implications of the language.

Daniel N. Paul We Were Not the Savages p. 85

Leaders that could laugh at themselves and tease their critics, that saw irony and absurdity as well as tragedy in their own lives, were to be trusted with the future.

Russell Barsh The Personality of a Nation p. 120

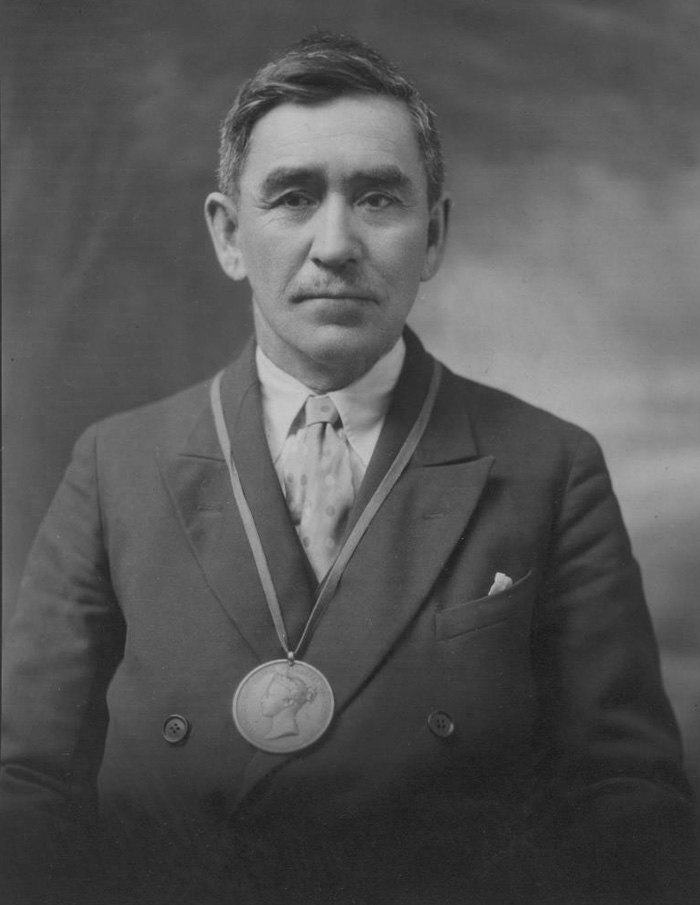

Designed by William Wyon, R.A. New Brunswick Museum /Musée du Nouveau-Brunswick 14430

Then your Fathers spoke to us

Peter Ginnish, Esgenoopetitj (Skno’pitijk) (Burnt Church), N.B., in The Micmac Indians of Eastern Canada by Wilson D. Wallis and Ruth Sawtell Willis

They said put up the axe

We will protect you

We will become your fathers

National Gallery of Art, Ottawa 4976

From the very beginning, Chiefs, Elders and their designates or representatives attempted to provide future socio-economic stability for their peoples. They agreed that the treaty agreements were permanent, legally binding contracts. In this lesson students will identify traits of some of the contemporary Indigenous leaders (Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqewiyik and Peskohtomuhkati (Passamaquoddy)) and the challenges they face.

The Peace and Friendship treaties concluded in the 18th century all followed a similar pattern. Their terms simply re-established peace and commercial relations. In these treaties, Indigenous peoples did not surrender rights to land or resources. Two of the treaties have a specific trade-related clause not found in the others, known as the “Truck House” clause. In the 1752 and 1760-1761 Peace and Friendship treaties, the British promised to establish a truck house, or trading post, for the exclusive use of the Indigenous signatories. As one of the primary purposes of the treaties was to re-establish trade within the colony, these “truck houses” would serve to encourage a commercial relationship between the Mi’kmaq, the Wolastoqewiyik, the Peskohtomuhkati (Passamaquoddy) and British settlers. While the actual trading posts were short-lived, the Truck House clause became the central focus of two different court cases in the 1980s and 1990s. In both the Simon and Marshall cases, Aboriginal claimants argued that the Truck House clause guaranteed Indigenous rights to hunt and fish throughout the region and to maintain a moderate livelihood there. There was a certain finality written into these Treaties. Here are some examples from different treaties:

1713 Treaty of Portsmouth — First treaty signed by Wolastoqewiyik. This treaty promised the Wabanaki people “free liberty for hunting, fishing, fowling and all other lawful liberties and privileges.” It followed ten years of war in which the Wabanaki had allied themselves with the French to resist English expansion. It also coincided with the Treaty of Utrecht between the English and the French, in which Acadia (present-day Nova Scotia and New Brunswick) had been ceded to the English. One of the translators, hired to translate the treaty for the Wabanaki, had been instructed by the British not to translate the treaty precisely. This was one of the major faults with treaty-making from the very beginning: very few of the Indigenous signers could speak the language the treaties were written in and none could read it, so they were totally dependent on translators. Although this treaty was signed by British representatives, as it was signed in what was then Massachusetts, it is not considered relevant in Canada.

1752 “We will not suffer that you be hindered from Hunting or Fishing in this Country as you have been used to do, and if you shall think fit to settle your Wives and Children upon the River Shubenacadie, no person shall hinder it, nor shall meddle with the lands, where you are, and the Governor will put up a Truck House of Merchandize there, where you may have everything you stand in need of at a reasonable price and where shall be given unto you to the full value for the peltries, feather, or other things which you shall have to sell.” — Section of a letter signed and sealed by His Excellency Peregrine Thomas Hopson, Esq. General and Gouvernor in Chief in and over his Majesty’s province of Nova Scotia or Accadie to the proposals made by Jean-Baptise Cope, for Himself and his Tribe and to his offers and Engagement to bring here the other Micmack Tribes to renew ye peace 1752.” (Peace and Friendship Treaty 1752)

1761 “During the winter, eight more Indian chiefs surrendered themselves, and the whole Micmac tribe, which then amounted to 6,000 souls, abandoned the cause of France, and became dependents upon the English. The following are the names of the Chiefs that signed the obligation of allegiance and their places of abode; Louis Francis (François), Chief of Miramichi; Dennis Winemower, of Tabogunkik; Etienne Abchabo (Aikon Aushabuc), of Pohoomoosh; Claude Atanage, of Gediaak (Shediac); Paul Lawrence (Laurent), of La Have; Joseph Alegemoure (L’kimu) of Chignecto or Cumberland; John Newit (Noel), of Pictou; Baptiste Lamourne, of St. John’s Island (Prince Edward Island); René Lamourne of Nalkitgoniash (Antigonish); Jeannot Piquadaduet (Pekitaulit) of Minas; Augustin Michael of Richibucto; Bartlemy Annqualet (Amquaret) of Kishpugowitk. The above Chiefs were sent to Halifax and on the 1st of July 1761, Joseph Algimault (L’kimu) (or as he was called by the Indians, Arimooch), held a great talk with Governor Lawrence. The hatchet was formally buried, the calumet (long stemmed pipe) was smoked … the several bands played the national anthem; the garrison and men-of-war fired royal salutes…” — Abraham Gesner, New Brunswick with Notes for Emigrants 1847 pp. 46 – 47

1761 “In this Faith I again greet you with this hand of Friendship, as a sign of putting you in full possession of English protections and Liberty, and now proceed to conclude this Memorial by these solemn Instruments to be preserved and transmitted by you with Charges to Your Children’s Children never to break the Seals or Terms of this Covenant.” — Honourable Mr. President Belcher assisted by His Majesty’s Council

Bequest of Dr. Louise Manning, 1989 108600

It is worth noting that there was little understanding of human rights at the time of these treaty signings. Liberty and equality were not popular in Europe until after the French Revolution. However, Indigenous leaders recognized that to secure peace and friendship, a relationship must be established based on a common understanding.

Canadian courts have recognized that the constitutional rights of Indigenous people were not created by Canadian legislation but predate the formation of Canada. Indigenous rights include language, culture, values, socialization, communal relations and customs, spirituality and religion, governance structures and lifelong learning.

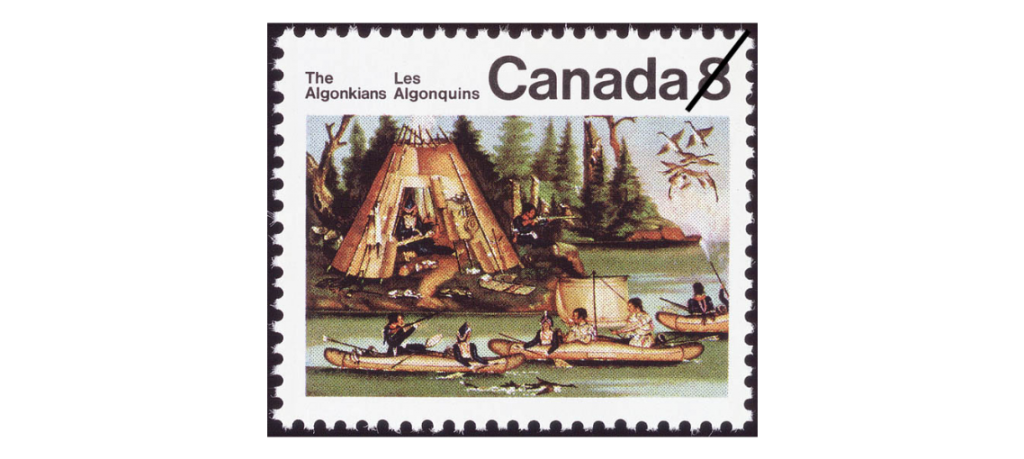

What is the relationship of the day of issue and the stamp?

A enlargement of the stamp is provided below. It shows a painting from around 1850 entitled “Micmac Indians” that hangs in the National Gallery of Canada.

The modern Treaty era began in 1973 with the Calder case, brought by the Nisga’a against the government of British Columbia. Since then, twenty-six arrangements – including treaties, umbrella agreements (treaty frameworks), and agreements in principle, which can take a long time to lead to a treaty – have been concluded. There are still over 100 modern treaties under negotiation. In exchange for extinguishing or modifying Aboriginal title to approximately ninety percent of their surface territory, First Nations receive hundreds of millions in cash. They are also able to form local or regional governments independent of the Indian Act. Finally, they must be consulted over activities that take place in their now-ceded territories. However, the government seems to view self-government as a gift bestowed by Canada on Indigenous peoples rather than a right being restored.

Indigenous peoples argue that their right to self-government exists because, historically, their societies had been organized and self-ruling. Often, the agreement process has lasted so long that at the end of it the First Nation has ended up owing tens of millions of dollars in accrued debt to Canada that comes off the top of any cash settlement.

As Crown agencies react negatively to Treaty Rights, Indigenous individuals expressing their rights are seen as deviant members of society. After court cases are resolved, they are viewed as heroes. The IDLE NO MORE movement is one example of mass action by Indigenous people to raise the consciousness of non-Indigenous people through their protests and educational campaigns.