Student Learning

I will be able:

- To appreciate and show respect for the Wabanaki right to claim sovereignty and self-determination through the example of the Peskotomuhkati (Teacher Directed)

- To demonstrate through using a map that international borders also split up Wabanaki traditional territories (Teacher Directed)

- To create a group mural which reflects sovereignty and self-determination, and which demonstrates an understanding of some of the topics of the unit (Activity 1)

- To explain how sovereignty and self-determination are not reflected in the actions of the Federal Government which has delegated authority passed down to First Nations. Legislative, executive and judicial powers have to be created through a Self-Determination Act in order for true sovereignty to emerge. (Activity 1 and 2)

Sovereignty is the right of a people to decide what their own laws and customs will be and to govern themselves. Sovereignty exists by itself. It cannot be given by one group of people to another, and it cannot be taken away. No matter what kind of government or powers a people exercise, sovereignty will not be affected or changed. Sovereignty comes first. It has been said by Wabanaki leaders that a sovereign nation that looks outward is stronger than one that looks out only for its own needs.

There is not always complete agreement on the question of sovereignty. After a period of three centuries, some individual First Nation communities feel oppressed. This may mean that they were put down by force, or simply ignored and prevented from further development.

The ruling in the Calder et al. v. Attorney General of British Columbia challenged this state of affairs. Here, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that Aboriginal (Indigenous) title exists in Canada even though the Government of Canada and the province had denied it. In Atlantic Canada, this meant that no treaties of “surrender” or purchases of Indigenous property had ever been signed. Further, it meant that Indigenous title and rights could possibly exist without any limitation. Most treaties attest to the right to hunt and fish (aboriginal/treaty rights). Canada just does not behave in accordance with the treaties’ intent. Hunting and fishing rights affirm uninterrupted dominion and economic access to original territories or treaty lands.

First Nations Leaders continue to demand their right to exercise their sovereignty through self-determination. One of the principal ways to do this is to bring the issue of self-government to the forefront. Self-determination does not guarantee a happy result; however, it provides an opportunity for Indigenous people to make the case for the entirety of legislative and judicial changes needed, as the Idle No More movement did in 2013. Instead, what has been happening between the Federal Government and First Nations is a reactive, issue-by-issue approach that is taxing, expensive, lengthy, and not necessarily linked to the overall need for change.

United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

This declaration was adopted by a majority of the General Assembly of the United Nations in New York on 13 September 2007, with 144 countries voting in support, 4 voting against and 11 abstaining.

What is the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples?

The Declaration is a comprehensive statement addressing the human rights of Indigenous peoples around the world. The document emphasizes the rights of Indigenous peoples to live in dignity, to maintain and strengthen their own institutions, cultures and traditions and to pursue their self-determined development, in keeping with their own needs and aspirations.

What rights are ensured by the Declaration?

The United Nations has defined ‘Nation’ as a “community of people formed on the basis of a common language, history, ethnicity, common culture and, in many cases, a shared territory.” Wabanaki peoples, like the Wolastoqewiyik, Mi’kmaq and Peskotomuhkati, who can demonstrate that this was the case prior to contact and during the early periods of contact can all define themselves as independent First Nations.

The Declaration addresses both individual and collective rights, cultural rights and identity, rights to education, health, employment, language, and others. Indigenous peoples and individuals are free and equal to all other peoples and individuals and have the right to be free from any kind of discrimination in the exercise of their rights, in particular, that based on their Indigenous origin or identity. Indigenous peoples have the right to self-determination. By that right they can freely determine their political status and pursue their economic, social and cultural development. They have the right to maintain and strengthen their distinct political, legal, economic, social and cultural institutions, while retaining their rights to participate fully, if they choose to, in the political, economic, social and cultural life of the state.

This document has certainly been a factor in re-establishing the Peskotomuhkati Nation in New Brunswick.

Click here to download the complete text of the Declaration: United Nations Official Document

Peskotomuhkati Nation

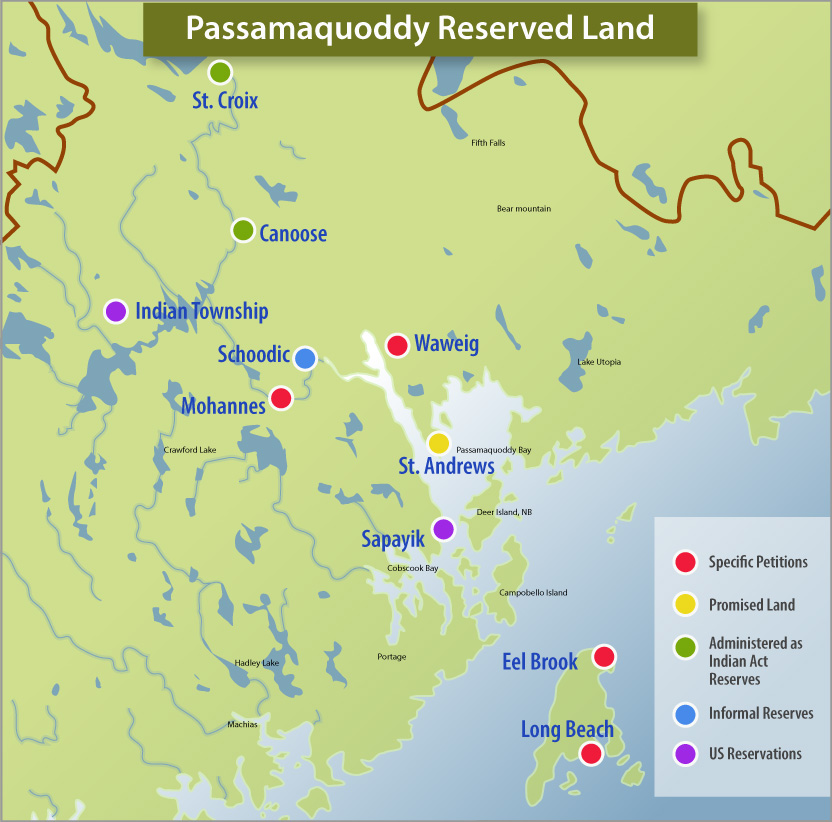

As an example of self-determination, the Passamaquoddy currently living in and around St. Andrews, New Brunswick, have been striving for sovereignty and recognition as a First Nation. As the land base of the Peskotomuhkati shrank, the colonial-minded federal government created the reserves. Into the twentieth century, there were two Peskotomuhkati reserves that were administered by the Indian Act — they were named the Canoose and St. Croix reserves. During the 1930s, the Indian Agent in Fredericton complained that the reserves were difficult to protect against American loggers coming across the river to harvest the timber, that no Indigenous people lived on the reserves, and that the reserves should be closed. Yet, even in the 1950s, one family, the Akagi, still lived on that reserve. Ramona Homan Akagi, for example, received Passamaquoddy (Peskotomuhkati) visitors from the other side of the bay in the same manner that chiefs had done for centuries. When she passed away, her son Hugh took over the responsibilities. In 1998, Hugh Akagi was elected Chief as well as traditional Sakom. For the next eighteen years, the Government of Canada refused to address him as “Chief”. However, this ended in 2016, when Minister of Indigenous and Northern Affairs Carolyn Bennett promised to complete the process of formal recognition as described in the Indian Act. Minister Bennett also promised she would be seeking a mandate to begin negotiations with the Peskotomuhkati Nation.

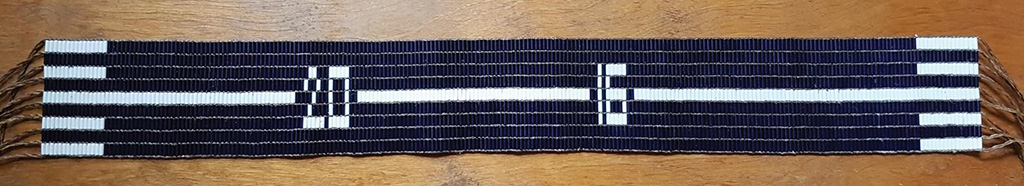

To commemorate the reaffirmation of the treaties in 2016, the Peskotomuhkati Council had a new wampum belt made. The white line from end to end of the wampum symbolizes the clear path of honest, open communications between the partners — “brother nations” — in the relationship (Canada and the Peskotomuhkati Nation). The four stripes at either end are a reminder that the Peskotomuhkati Nation is part of the Wabanaki Confederacy.

Responsibilities of First Nations

First Nations expect to retain responsibility for transmitting their forms of social and cultural organization, their spiritual beliefs, and their skills and knowledge pertaining to their communities’ economic development to future generations. They expect to retain the authority and capacity to govern their own people according to their laws and systems of justice. They would respect the laws of the Crown outside of their own jurisdiction, and in return, the Crown would respect the authority of the First Nations in matters of governance over their own lands and people. All these rights are claimed on the grounds of having been a nation prior to the arrival of Europeans. The legal framework of the self-determination model would be based on Indigenous law (Wolastoqey, Mi’kmaw, Peskotomuhkati).

In 2010, the Supreme Court of Canada recognized that the Treaties between the Crown and Indigenous nations are about building relationships. Reconciliation has become a goal within the Constitution of Canada (Section 35).

The Peace and Friendship Treaties and their part in the Covenant Chain of Treaties are a bridge to the future. More than mere documents or transactions, treaties shape our relationships as Canadian and Indigenous peoples. These treaties did not transfer ownership of land to the British Crown. The spirit and intent was for the settlers and the Wabanaki people to live in Peace and Friendship.

A treaty comes into effect and endures over time to ensure peaceful coexistence. Canadian and First Nations leaders continue to negotiate Treaties with a view to ensuring that common interests in future economic and cultural activities remain stable for their peoples.

Supreme Court ruling could help Wabanaki people on Maine border (Jacques Poitras, CBC)

The Peskotomuhkati traditional territory straddles New Brunswick-Maine border

A Supreme Court of Canada ruling extending Aboriginal rights to some non-Canadian Indigenous people could have wide-ranging implications for the Peskotomuhkati living on both sides of the Maine-New Brunswick border. The decision says that U.S.-born Indigenous people with historical connections to territory now in Canada have rights under the Canadian Constitution.

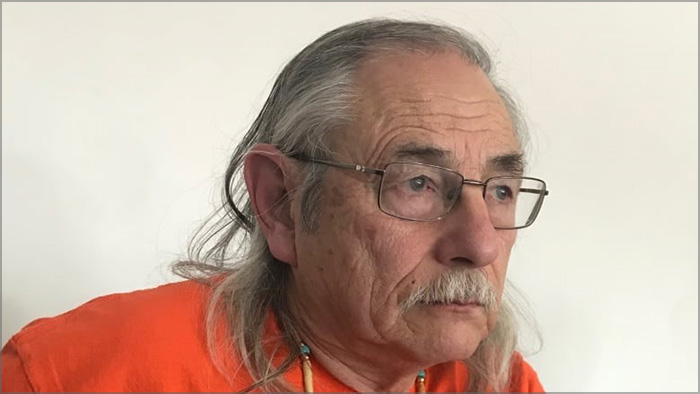

“My people are already affected by everything around this ruling, so I’m hoping that this ruling actually helps us to basically reinforce what we’ve been saying all along: how we are one people, one nation,” said Chief Hugh Akagi of the Peskotomuhkati, also known as the Passamaquoddy Nation.

Their traditional territory straddled the St. Croix River, which forms part of the border between New Brunswick and Maine.

“Yes, we’re divided by territory, a boundary, a border and a river, but the truth is we’ve been saying to the world that we’ve always been one people,” Akagi said.

Last week, the top court ruled that an American member of the Sinixt Nation had a right to hunt in British Columbia because his people’s traditional territory included parts of B.C. before the drawing of the Canada-U.S. border.

“Persons who are not Canadian citizens and who do not reside in Canada can exercise an Aboriginal right” under the Constitution, the court said, if they are “modern-day successors of Aboriginal societies that occupied Canadian territory at the time of European contact.”

The B.C. case involved Richard Desautel, an American citizen who killed an elk without a hunting licence in October 2010. The court ruled 7-2 that Section 35 of the Constitution, which recognizes the rights of “Aboriginal peoples of Canada,” extended to Desautel.

It marks the first time the country’s top court has interpreted the meaning of the phrase “of Canada” in Section 35. Desautel lives on a reserve in Washington State and is a member of the Lakes Tribe of the Colville Confederated Tribes, considered a successor group to the Sinixt, whose territory included the part of present-day B.C. where he was hunting.

The court said hunting was a continual part of a traditional practice that existed before European colonization and before the Canada-U.S. border was drawn there in 1846. “An interpretation of ‘Aboriginal peoples of Canada’ … that includes Aboriginal peoples who were here when the Europeans arrived and later moved or were forced to move elsewhere, or on whom international boundaries were imposed, reflects the purpose of reconciliation.”

The ruling has also caught the attention of a Wolastoqey community just across the Canada-U.S. border from Woodstock, N.B.

Discuss

What do you think the chances are that the Peskotomuhkati will have success with the Supreme Court ruling? Why or why not? What arguments would you use to present your case?

Some Elders have offered the following advice for reaching self-determination:

- Love our communities, even if some of them don’t know yet how to love themselves

- Forgive each other for the many ways in which colonization has divided us

- Don’t focus solely on the barriers or you give them too much power

- Live, act, and assert our sovereignty every day or we lose it