Purpose

The purpose of this lesson is to introduce students to Waponahkewiyik (Wabanaki) worldview. Medicine Wheel Teachings are used as a teaching tool to promote holistic thinking and to begin to see interconnections within the natural world. Developing an understanding of Waponahkewiyik (Wabanaki) worldview is essential to understanding Waponahkewiyik (Wabanaki) perspective during Peace and Friendship Treaty negotiations.

Student Learning

I will be able:

- To explore Ta’n tel-pilu’ – nmitmk wskwitqamu Wabanaki Worldview Waponahkewiyik Piluwamsotuwakonol. (Activity 1)

- To explore and discuss Kiwto’qikit Nepisimkewey Medicine Wheel Teachings Woli Pomawsuwakonol as a means of understanding Wabanaki Worldview. (Activity 1)

- To create a piece of artwork demonstrating understanding of some aspect of Medicine Wheel Teachings and be able to discuss the intent of my work. (Activity 1)

- To explore the concepts of Netukulimk Seventh Generation Thinking Woli Pomawsuwakon through videos and small group/class discussion and be able to present ideas creatively in a manner of my choosing. (Activity 2)

- To deepen my relationship with the natural world by going on a nature walk, sitting quietly observing, and spending time reflecting on my experience. (Activity 3)

- To reflect on my learning in a more holistic way, involving Mind, Body, Heart and Spirit. (Activity 3)

This we know. The Earth does not belong to man, man belongs to the earth.

Chief Seattle, 1790 – 18661

All things are connected like the blood that unites one family.

Man did not weave the web of life, he is merely a strand in it.

Whatever he does to the web, he does to himself.

Beginning in the 1700s, treaties were signed between the British Crown and Waponahkewiyik (Wabanaki Nations). The Peace and Friendship Treaties between the British and Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqewiyik, Peskotomuhkati, (Passamaquoddy), Panuwapskewiyik (Penobscot), and Aponahkewiyik (Abenaki), were some of the earliest treaties signed. Each treaty reaffirmed the tpelotagan treaty relationship kci lakutimok between the British and Waponahkewiyik and laid out a path for moving forward respecting each other’s rights and ways of life. Section 35 of the Canadian Constitution recognizes and affirms these treaty rights.

The Peace and Friendship treaties were documented in written form, in English, by the British. However, British and Waponahkewiyik representatives saw the world in very different ways and spoke different languages. Our understanding of the treaties is incomplete if we do not appreciate the spirit and intent of the Peace and Friendship treaties from a Waponahkewiyik (Wabanaki) perspective.

To start to understand a Waponahkewiyik perspective of the Peace and Friendship Treaties, we need to first examine Waponahkewiyik worldview. (You can also find valuable insight about Waponahkewiyik Worldview on the New Brunswick Office of First Nation Education’s World of Wisdom website – https://world-of-wisdom.ca/.)

A Note on Elder Involvement

Whenever possible, it is ideal to involve Waponahkewi Elders and knowledge keepers in your classrooms when discussing Waponahkewiyik worldview with your class. Waponahkewi Elders are the “Language and Culture Carriers” for Waponahkey communities. They are the “Wisdom Keepers” for current and future generations. Inviting Elders to participate in classes demonstrates respect for them and the wisdom they carry and provides them with an opportunity to share their knowledge with students. Elder knowledge is critical in studies that examine values, beliefs and ethics of Waponahkewiyik.

Perley, I. (2021). Wabanaki Worldviews course syllabus (ED 5043/ABRG 4686). University of New Brunswick.

What is Worldview?

Wolastoqewi Elders Dr. David Perley and Dr. Imelda Perley want students to appreciate that worldview “consists of the principles we acquire to make sense of the world around us. Young people learn these principles, including values, traditions, and customs, from myths, legends, stories, family, community, and examples set by community leaders” (Yupiaq scholar Oscar Kawagley, 2006, 7).

Worldview encompasses a wide range of beliefs and concepts that are interrelated and interconnected, especially language and culture, but also include spirituality, upbringing, and personal experiences. Worldviews can vary significantly from one culture to another and one person to another. It is important to approach the topic of worldview with sensitivity and respect.

Waponahkewiyik (Wabanaki) Worldviews

Waponahkewiyik worldview, like those of all other First Nations across Canada, is deeply connected to language. Our Elders believe that our language connects us to our ancestral teachings and promotes a worldview that emphasizes respectful relationships between human beings and with all of creation.

Language is not only a means of communication but also a carrier of cultural heritage, ecological knowledge, identity and spirituality. Language plays a fundamental role in how Waponahkewiyik understand our place in the world.

For example, Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqey and Peskotomuhkati (Passamaquoddy) languages are relational and express relationships with and within all of creation. The following table provides some examples of Mi’kmaw and Wolastoqey words that express these relationships.

Vocabulary

| English | Mi’kmaw | Wolastoqey Latuwewakon |

|---|---|---|

| Our Sacred Mother Earth | Kkijinu Maqamikew | Kci Kikuwosson |

| Earth Walkers | Mimajuinu’k | Skicinuwok |

| All living beings are related | Kmimajuagnminal | Psonakutomuwakonol |

| All my relations | Msɨt No’kmaq | Psiw Ntolonapemok |

| Living in a respectful way with the environment to ensure sustainability | Netukulimk | Woli Pomawsuwakon |

| Interconnectedness | Wetapeksin | Kci Mawawsultimok |

Waponahkey languages and worldviews provide a cultural lens for how Waponahkewiyik see and experience the world, and how we relate to the world. The language we use tells us how we feel about Kkijinu Maqamikew Mother Earth Kci Kikuwosson and all of creation that dwells on her and with us.

Kejitu’sɨp? Did you know? ‘Kocicihtuness?

In Wolastoqey Latuwewakon (language) there is no word for “the”?

Earth is never referred to as “the earth” but always as Kci-kikuwosson – Mother Earth.

Try saying “the earth” and “Mother Earth.” How do you feel in each instance?

The word “the” objectifies creation and leads to people feeling separate from instead of in relation with creation.

How would you treat our rivers and lands differently if you thought of them as your relatives?

Much more will be presented on the importance of language and its connection to worldview in the next lesson, Lesson Plan B: Language From This Land.

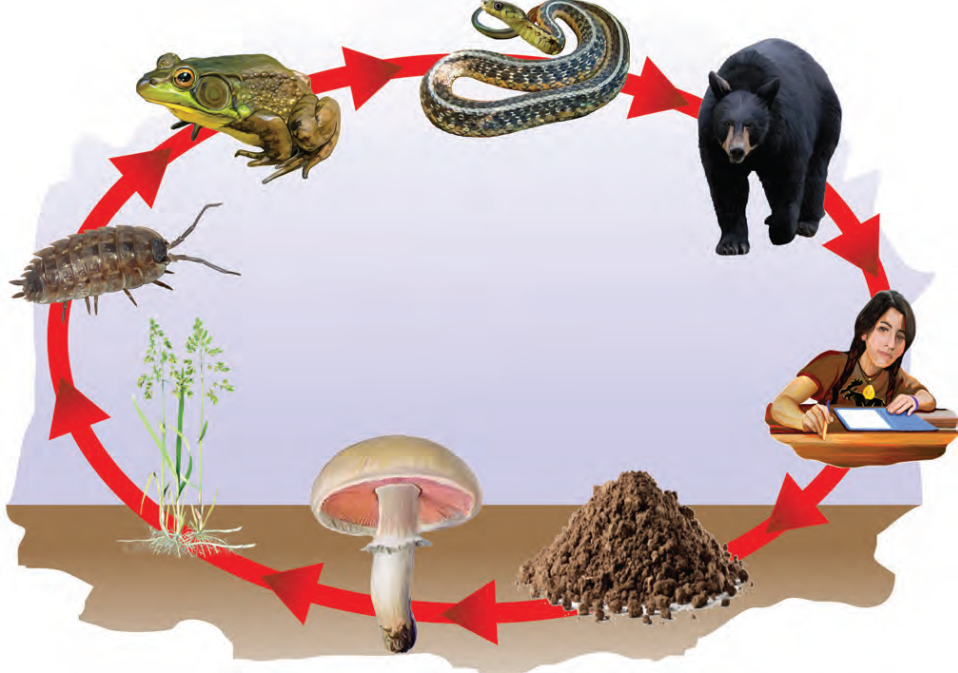

Waponahkewiyik (Wabanaki) worldview is reflected in the phrase Msɨt No’kmaq All my relations Psiw Ntolonapemok, which acknowledges that we are related not only to other humans, but also to four-leggeds, finned-ones, winged-ones, standing ones (tree people), earth crawlers and all of creation.

Since all of creation, including humans, are related, then we are also responsible for and accountable to all of creation and each other. All of creation is interdependent and we seek to maintain balance and harmony in the world.

This interconnectedness is called Wetapeksin or Kci Mawawsultimok. Giving thanks to all that is around us leads us to acknowledge the interdependence of life. The relationship between thinking and doing is critical – living what you know is at the heart of Wetapeksin or Kci Mawawsultimok. By seeing yourself as living with the environment and being part of the cycles of life, you are viewing the world from the inside out rather than the outside in.

Before contact with Europeans, Waponahkewiyik (Wabanaki) lived for thousands of years in a way that balanced the needs of people and those of our natural world. Waponahkewiyik (Wabanaki) worked to conserve natural resources they relied upon for food, shelter and clothing. This way of living in balance with nature ensured that essential resources would always be there for generations to come. This is whom and what Waponahkewiyik ancestors fought to protect when they negotiated and signed treaties with the British.

As Skicinuwok – Earth Walkers – we have responsibilities. One of these responsibilities is to make sure that Mother Earth is always healthy. We have to respect Mother Earth. She has a spirit, and we have to make sure that when we walk on Mother Earth we have to walk in beauty, and ensure that when we leave this world and move on to the spirit world that what we leave behind is a healthy Mother Earth. So we have responsibilities as Earth Walkers, and we learn these responsibilities from our Elders, which are passed on from one generation to another generation.

Wolastoqewi Elder Dr. David Perley, 20212

Desiring to leave Mother Earth healthy and plentiful for future generations is often referred to as Netukulimk Seventh Generation thinking Woli Pomawsuwakon. This means living in a respectful way with the environment to ensure and honour sustainability and prosperity for the ancestor, present and especially for future generations. For example, when sweetgrass – Mother Earth’s hair – is being harvested, Waponahkewi Elders teach that you should leave the first one you find, then leave the second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh and pick the eighth. This shows deep respect and contemplation because you leave behind enough for the seven generations yet to be born.

Netukulimk Seventh Generation thinking Woli Pomawsuwakon ensure sustainability and reciprocity and demonstrate that Waponahkewiyik recognize the need to respect and value their first treaty relationship – the one with Mother Earth and all of her family. Since you are part of this family, it is also a treaty with yourself.

Becoming indigenous to a place means living as if your children’s future mattered, to take care of the land as if our lives, both material and spiritual, depended on it.

Robin Wall Kimmerer, 2013, p.9

Medicine Wheel Teachings

Medicine Wheels are powerful symbols for many Indigenous Nations. It is important to note that different nations have different teachings and different understandings about medicine wheels, and may use different colours, or present the colours in different orders according to their stories, values and beliefs. This does not mean one set of teachings is more correct than another. Each Nation and each Elder uses what works best for them.

However, there are fundamental similarities among medicine wheel teachings from different Indigenous nations. Medicine Wheel teachings are holistic and teach about the interconnectedness of all creation and the importance of balance and harmony of the physical, emotional, mental and spiritual realities.

The Medicine Wheel is not Wolastoqey or Mi’kmaq in origin; these Wabanaki Nations did not use this as a tool historically. However, in recent decades, Medicine Wheel teachings have been shared and interpreted between Indigenous Nations as a holistic tool to use in healing practices. These are powerful teachings for understanding Waponahkewiyik worldviews.

In this Lesson Plan, we present Medicine Wheel teachings described by Wolastoqewi Elders Opolahsomuwehs (Moon of the Whirling Wind) Imelda Perley and David Perley, and by the late Elder Sagatay (The Light before the Dawn) Gwen Bear.

In Wolastoqey, Medicine Wheel teachings are called Woli Pomawsuwakonol, or Sacred Earth Walk.

Mi’kmaq refer to Medicine Wheel teachings as Kiwto’qikit Nepisimkewey.

Medicine wheels are considered a sacred symbol and are represented by a circle divided into four areas, or quadrants.

Mi’kmaq Medicine Wheels are oriented slightly different, but the underlying teachings are largely the same. For instance Mi’kmaq Medicine Wheels often have the colour yellow in the east, red in the south, black in the west, and white in the north.

According to Wolastoqewi Elders Opolahsomuwehs (Moon of the Whirling Wind) Imelda Perley, and David Perley, it is important to look at both terms:

- Medicine refers to traditions, ceremonies, beliefs, values, ideals, worldviews and language, as well as sacred plant medicines from Mother Earth.

- Wheel represents the sacred circle of life, including the many cycles and recurring patterns that are found in nature and throughout our journey of life. The circle of life as found in changing seasons and in lifespans of plants, animals, and humans is a reminder that everything flows in a circle and/or cycle.

Kejitu’sɨp? Did you know? ‘Kocicihtuness?

The term “medicine wheel” was first used by Americans of European descent in the early 1900s to describe the ancient stone Big Horn Medicine Wheel in Wyoming. The wheel rests within Crow homeland, though their oral history states that the Big Horn Medicine wheel existed prior to their arrival.

At present, over 70 ancient medicine wheels, with a central cairn and/or spokes and outer rings, have been identified throughout the northern Plains from Wyoming, South Dakota, and North Dakota to Alberta and Saskatchewan. They are most numerous in Alberta, which has 57 document medicine wheels.

Archaeological studies indicate the earliest medicine wheel sites can be dated to 4,500 – 5000 BC, and they were likely used for ceremonial purposes by several ancestral Indigenous cultural groups.

Sources:

- Medicine Wheel/Medicine Mountain National Historic Landmark https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Medicine_Wheel/Medicine_Mountain_National_Historic_Landmark

- Indigenous Corporate Training Inc. (2020). What is an Indigenous Medicine Wheel. https://www.ictinc.ca/blog/what-is-an-indigenous-medicine-wheel

- The Canadian Encyclopedia. (2015). Medicine Wheels. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/medicine-wheels?gclid=CjwKCAiAhreNBhAYEiwAFGGKPD0VRf6hsSpJzo3tuV8JYQnz0BebBdUhCdvtdTBOSh2MnZVEKRrhRhoCWBQQAvD_BwE

- Cookson, Cory. (2020). The 9 types of Medicine Wheels in Alberta. https://emberarchaeology.ca/the-9-types-of-medicine-wheels-in-alberta/

The Medicine Wheel does not teach one lesson. Rather it contains an endless source of lessons. Each of these lessons reinforces the seven gifts [of love, honesty, humility, respect, truth, patience and wisdom] and the need for balance in our lives. The Medicine Wheel shows us respect for all races of the earth and the gifts which they bring. Then again, it reminds us of the seasons, the warm breezes, the newness of each day, the sprit in all things and the clarity of spirit among Elders and children. … Balance of the body, intellect, spirit and environment are also represented in the Medicine Wheel. Most of all, it honours the wisdom of Mother Earth, building on her example of cycle and change.

Mi’kmaq Elder Albert Marshall3

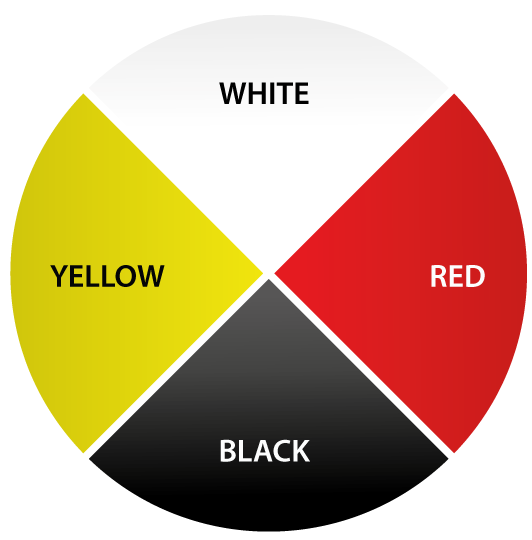

Sacred Colours of Humanity

Four different colours are assigned to each quadrant of medicine wheels. Four (of the seven) sacred colours of creation are used in Waponahkey medicine wheels: red, black, yellow and white. Note that the Mi’kmaw and Wolastoqey terms for red, black, yellow and white are animate, representing the connection to humans and all living beings.

Three other sacred colours are recognized: blue for sky and water; green for grass and trees and all plant life; and brown for Mother Earth and her sacred medicines.

| English | Mi’kmaw | Wolastoqey Latuwewakon |

|---|---|---|

| Red | Mekwe’k | Mehqeyu |

| Black | Maqtawe’k | Mokoseweyu |

| Yellow | Wataptek | Wisaweyu |

| White | Wape’k | Wapeyu |

| Blue | Pkumanamu’k | Mosqonocihte |

| Green | Stoqnamu’k | Stahqonocite |

| Brown | Tupkwanamu’k | Tupqanocihte |

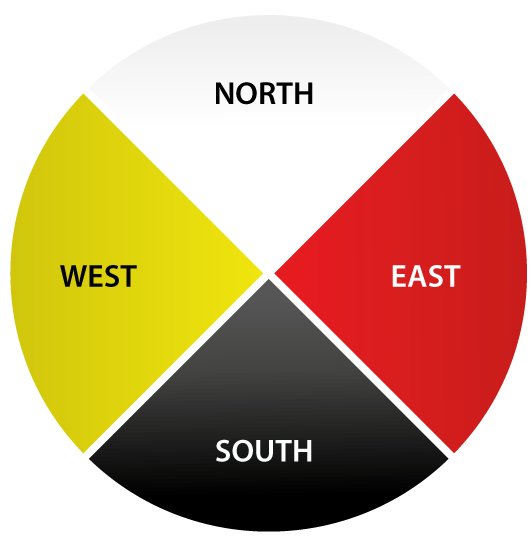

Four Directions

The four quadrants of the medicine wheel also represent the four points of the compass: East, South, West, and North. In Waponahkey medicine wheel teachings, the colour red is usually in the East because Wapon means “first light” and Waponahkewiyik are “people of the first light” or people of the Dawnland.

Waponahkewiyik honour seven directions. In addition to East, South, West, North, the additional directions include:

- Above to Creator, sky, Grandfather Sun and Grandmother Moon;

- Below to Mother Earth, and

- Within to ourselves and the seven-generation spirit that exists within us.

| English | Mi’kmaw | Wolastoqey Latuwewakon |

|---|---|---|

| East | Wjɨpenuk | Cipenuk |

| South | Pkɨtesnuk | Sawonehsonuk |

| West | Tkesnuk | Skiyahsonuk |

| North | Oqwatnuk | Lahtoqehsonuk |

| Above | Ke’kwe’k | Ewepiw |

| Below | Epune’k | Emekew |

| Within | Lame’k | Lamiw |

These seven directions are honoured in many sacred ceremonies that Waponahkewiyik engage in.

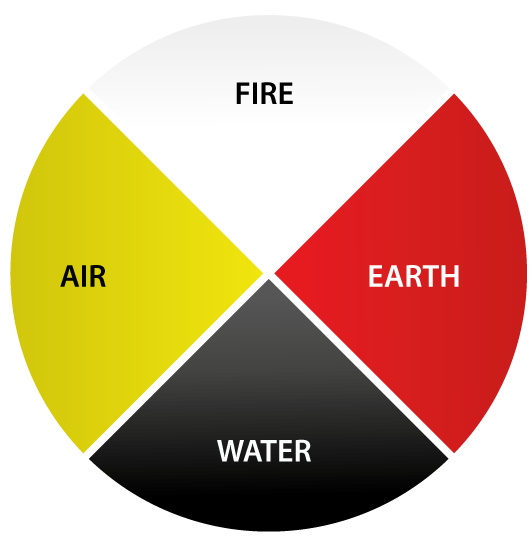

Four Elements

The quadrants also represent the four elements found in nature.

- East (red) represents earth,

- South (black) represents water,

- West (yellow) represents air,

- North (white) represents fire.

| English | Mi’kmaw | Wolastoqey Latuwewakon |

|---|---|---|

| Earth | Wskwitqamu | Skitkomiq |

| Water | Samqwan | ‘Samaqan |

| Air | Wju’sn | Ewon |

| Fire | Puktew | Sqot |

An important medicine wheel teaching is about the importance of balance and harmony. Today, because of climate change and the poor care we have shown Mother Earth, these four elements seem to be out of balance. This can be visualized using a Medicine Wheel by drawing the Fire quadrant larger than the rest, to represent industry and human beings’ race for progress. What happens to the other three quadrants when Fire consumes more than its fair share?

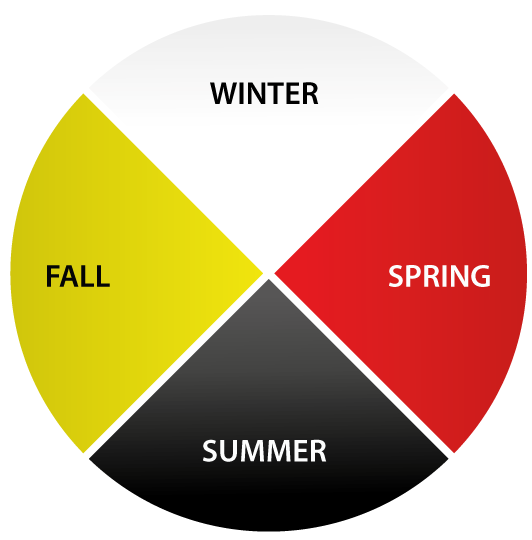

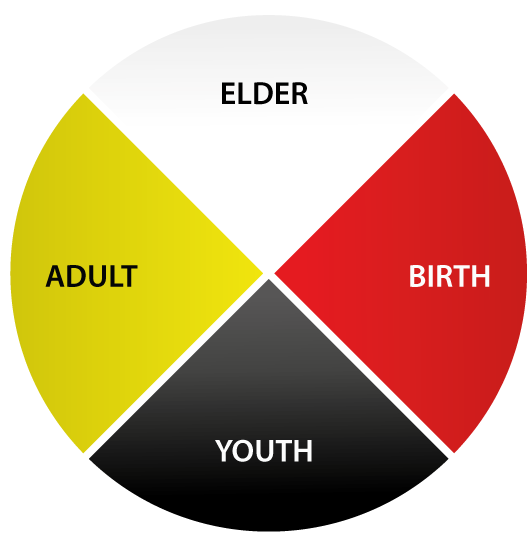

Four Seasons and Four Stages of Life

Waponahkewiyik see symmetry between the four seasons and four stages of life.

- Spring, a time of new life arises in the East. This also represents birth and infancy. Waponahkewiyik believe infants have recently come from the spiritual realm, like the sun rising in the east.

- Summer follows in the South, which also represents youth, a time of great growth and emotional development.

- Fall arrives in the West, aligning with Adulthood when one’s physical body is matured.

- Winter follows in the North, a time for rest and introspection (looking within) and renewal. This also represents the Elder stage of life, when one has experienced life and acquired wisdom to share with all.

Four Seasons

Stages of Life

| English | Mi’kmaw | Wolastoqey Latuwewakon |

|---|---|---|

| Spring | Siwkw | Siqon |

| Summer | Nipk | Nipon |

| Fall | Toqwa’q | Toqaq |

| Winter | Kesik | Pun |

| Birth | Wskwitqamuit | Nomihqosu |

| Youth | Mijua’ji’j | Skinuhsis (boy) / Pilsqehsis (girl) |

| Adult | Kisikwet | Skitap (man) / Ehpit (woman) |

| Elder | Kisiku’mimajuinu | Kcicihtuwinut (one who carries knowledge) |

Kejitu’sɨp? Did you know? ‘Kocicihtuness?

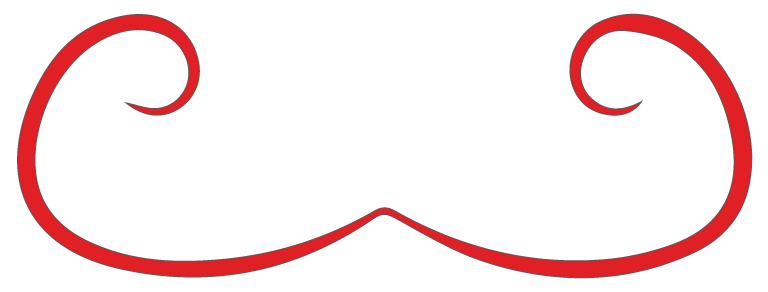

Waponahkewiyik also use the double curve motif to represent the journey of life, from spirit to physical growth in the womb, through their earth walk, and back to spirit within Mother Earth’s womb. It is a pattern found often in nature, like the coil of a fiddlehead. Wolastoqewiyik, Mi’kmaq, and Peskotomuhkati double curve motifs are all slightly different and are symbolic for each nation.

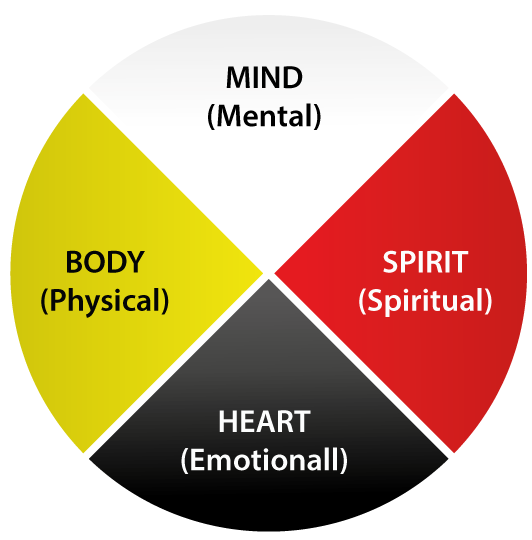

Four States of Being / Domains of Personal Growth

Medicine wheel teachings also serve as a guide for personal growth and self-discovery. These teachings remind us that we all have spiritual, emotional, physical, and mental gifts and we need to nurture these gifts to be in balance. By understanding and aligning with these teachings, individuals can work toward becoming more balanced, aware, fulfilled, and joyful human beings with purpose.

| English | Mi’kmaw | Wolastoqey Latuwewakon |

|---|---|---|

| Spirit | Jijaqamij | Cocahq |

| Heart | Kamulamun | Psuhun |

| Body | Ntinnin | Hok |

| Mind | Ta’n Wejita’simk | Tpitahasuwakon |

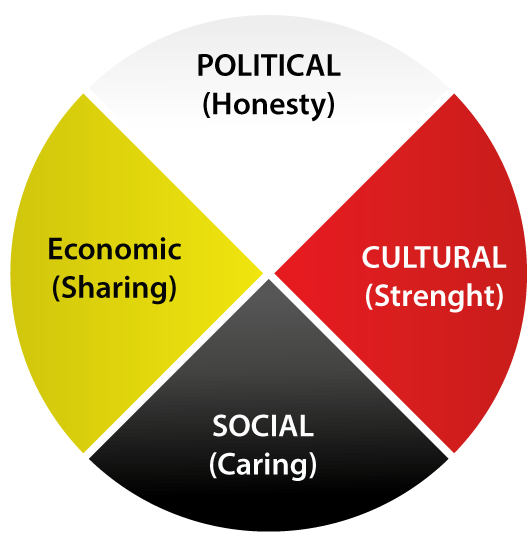

Four Domains of Rights and Responsibilities

Wabanaki medicine wheels also teach us about our four domains of rights and responsibilities.

First, we are introduced to the cultural realm during our infancy, from which we can draw cultural strength for our earth walk. During youth, we explore the social realm and learn to have compassion and care for others. During our adulthood, we have economic responsibilities and must learn to share with others who have less than us. And finally, during our Elder years, we gain more political knowledge and must speak the truth.

| English | Mi’kmaw | Wolastoqey Latuwewakon |

|---|---|---|

| Cultural | Klu’skap | Eleyimok |

| Social | Wiaqqatmu’tijik | Mawawsultimok |

| Economical | Suliewey | Wetawsultimok |

| Political | Kɨpnno’l | Putuwasultimok |

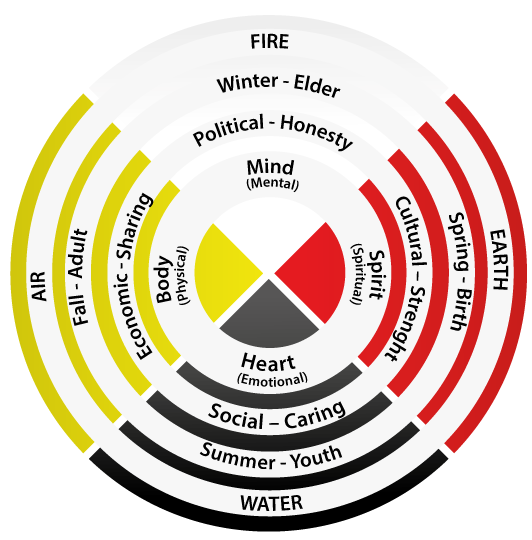

It is important to know that these Medicine Wheel teachings are interconnected and intersect with each other. That is why they are often presented as concentric circles, instead of a series of separate circles, as shown above for simplicity.

For instance, Waponahkey medicine wheel teachings can be represented by the following image.

Summary

Medicine wheel teachings demonstrate that all aspects of life are interconnected. All creation on Mother Earth was put here for a purpose, and we are all deeply connected. Our connection to the land and to Mother Earth can directly affect our spiritual well-being. Likewise, we have a responsibility to take care of Mother Earth and all of creation, on which we depend for sustenance. The health of Mother Earth is directly connected to our own mental, physical, emotional and spiritual health.

This sense of interconnectedness, responsibility for and reciprocity with Mother Earth and all earth dwellers formed the foundation for Waponahkewiyik thinking during Treaty negotiations.

- Ted Perry, film script for Home (prod. by the Southern Baptist Radio and Television Commission, 1972), reprinted in Rudolf Kaiser, “Chief Seattle’s Speech(es): American Origins and European Reception,” in Recovering the Word: Essays on Native American Literature, ed. Brian Swann and Arnold Krupat (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987), 525-30. ↩︎

- Perley, D. (2021, January 13). Wabanaki Worldviews [Guest Lecturer in Dr. Imelda Perley’s class]. University of New Brunswick. ↩︎

- Marshall, A. (2005). The science of humility. WIPCE conference paper. Available through The Institute for Integrative Science & Health, Cape Breton University http://www.integrativescience.ca/uploads/articles/2005November-Marshall-WIPCE-text-Science-of-Humility-Integrative-Science.pdf ↩︎

- Perley, I. (2021, January – April). Wabanaki Worldviews. University of New Brunswick. ↩︎