Materials required: logbook, objects or photos of objects, whiteboard, projector

Write the following question on the board and direct students to take a piece of paper in their logbook and write down some ideas.

What makes a good trade?

Give students 1-2 minutes after the beginning of the class to finish their lists. Go around the room and ask each student for one of their answers and list them on the board under the question. If there are similar answers place hash marks next to the answer to show how many students had that on their list. Ask students if there is anything on the list they disagree with or anything left off.

If no student indicates that traded objects need to be of similar value, try to steer them towards that idea by randomly selecting a student and have them choose an object from their backpack. Depending on what object they have chosen, choose something of much lesser value and offer to trade them your object for theirs. If the student refuses, ask him/her why?

Now ask –

How do you determine the value of things?

Break the students into 4 equal groups and give them an actual object or a photo of an object and ask them to determine what they need to know about that object to give it a value.

Questions could include:

- What is it made of?

- How long does it take to make this object?

- How hard are the resources to find in order to make the object?

Here are some objects:

Maskwiey Kwitn

Birchbark canoe https://vimeo.com/16573771 * Short film

Kwitn

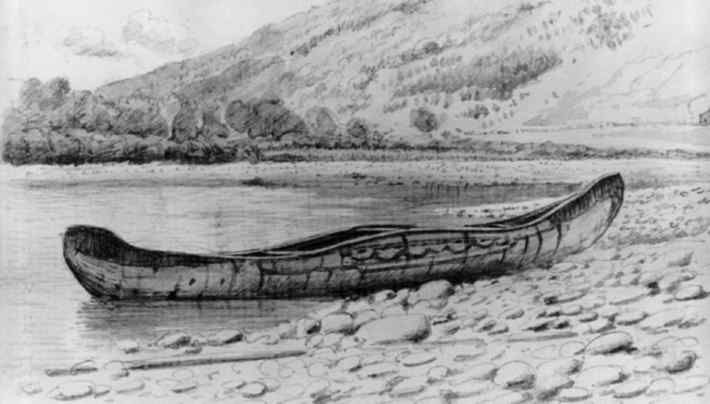

The canoe or Kwitn of the Mi’kmaq was unique in its design. It looked very different from any other canoe in North America, perhaps the world. It had raised sides and a much lower bow and stern than most other canoes. There were at least two reasons for the high sides: 1) to prevent waves from splashing into the canoe while crossing large bodies of water, and 2) to allow for more leverage while pulling up a large fish or seal during ocean fishing expeditions.

The Mi’kmaq used several different sizes of canoes. Some were as small as 12-13 feet long, for use in the many smaller rivers and streams, but the usual size was about 16-18 feet, used on the larger rivers. Large 20-24 foot canoes were used on the ocean and in the bays of Eastern Canada.

“The canoe was the main source of transportation for the Mi’kmaq. If you look at a map of Eastern Canada, it is easy to see why. There are numerous rivers, lakes, and bays to be traversed and used as roads. In order to get to most parts of Mi’kmaq territory, you will need to cross water or travel up or down a river or two. The canoe was indispensable to the Mi’kmaq.”

Joe Wilmot, Listuguj, Québec

Above are two pictures of canoes — one Mi’kmaw and one Wolastoqey. What are they made from? How are the designs similar? How are they different? What is the motif at the front of the Wolastoqey canoe? Could you say the same thing about the uses of a Wolastoqey canoe as we did about the Mi’kmaw canoe?

Kuowey Kwitn Pine Dugout Canoe:

Jean-Claude Robichaud, New Brunswick Museum-Musée du Nouveau Brunswick-2006 2006.34

The oldest canoe found in New Brunswick is the dugout canoe found in Val Comeau. It dates back to 1557. Its construction involved the selection of a large tree and the removal of the outer bark. This caused the tree to die and made it easier to harvest. The tree was then felled by using stone axes and adzes. Burning away part of the surface made the task less laborious. How long do you think this whole process took? This kind of dugout canoe would be used to transport supplies and people on longer rivers and coastal shorelines to outer islands.

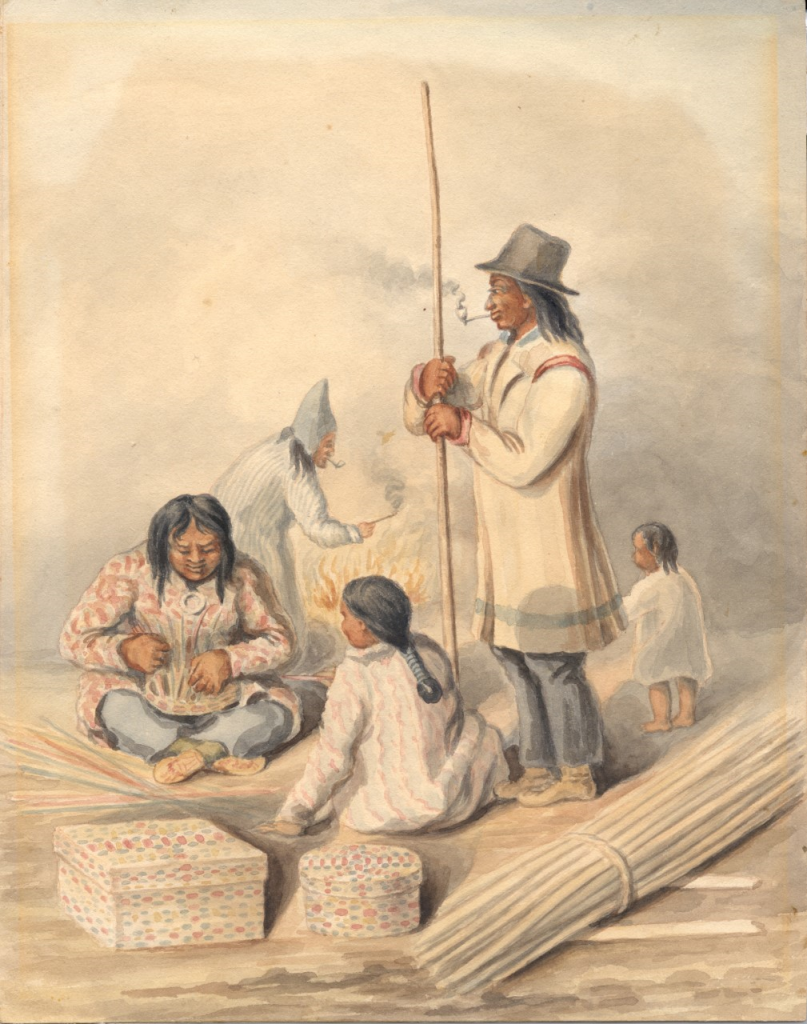

Likpnikn / Basket / Posonut

David Moses Bridges, Passamoquoddy – birchbark baskets and canoes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kan4nktVeR0&list=UUMG5Y4CDmcxXv_dcT7jogJA&index=10

Provincial Archives New Brunswick CA-31

A film without words that shows how baskets are made can be viewed at http://www.wapikoni.ca/films/my-fathers-tools-les-outils-de-mon-pere. This film is called My Father’s Tools – Les Outils de mon Père by Heather Condo, 2017. In honour of his father, Stephen Jerome makes traditional baskets in his workshop. While doing this, he finds peace through his work uniting him with his forbears, who taught him this skill.

New Brunswick Museum-Musée du Nouveau-Brunswick 5179.1. Source.

Pu’taliewei

Pu’taliewei or ash basket has always been associated with the Mi’kmaq so much so that we are referred to as the basket weavers, basket people by some First Nations. That is my experience while working with workers from other tribes. The black ash (wisqoq) is the tree of choice by most basket-makers, although good baskets can be made from just about any tree in North America. The black ash’s growth rings can be separated by pounding with a heavy object like a limb of a harder tree such as a maple (snawey). Once the rings have been separated or split they are cut into long strips which are then woven into baskets of every size and use, from a hunting back pack (nutawletat’g) to a large laundry basket/hamper or to a little basket to store small delicate items. The top ring and a handle are usually made of white ash (aqamo’q) so the wood does not split.

There is a way to make a certain weave which makes the basket watertight for a long time, maybe while on a river trip or to use in the rain. Basket-making families have been able to supplement their household income during the hard times by selling their creations. As long as there were ash trees around, they never went hungry. I heard a story of a young man who after not finding work in the United States started making baskets there and after a while made enough money from selling his baskets not to need to find a job.

Joe Wilmot, Listuguj, Québec

Pqwa’lu’skwewey wow / Clay pot without a kiln / Qahqolunsqey

Marvin Bartel https://www.goshen.edu/art/DeptPgs/rework.html

Ji’nmuey Tetpiaqewe’l wkotml/ Man’s ceremonial coat / Kci Olotahkewakoney Opsqons

New Brunswick Museum – Musée du Nouveau Brunswick 30116. Source.

Have each group research through books or online to find out how long and how difficult these items are to make. Use the pictures or references above. Once all groups have presented their findings, ask the questions.

- Do the resources you have available near your home make you determine the cost of an item?

- Which of these items (above) would Europeans most value? Indigenous groups? Why?