Student Learning

I will:

- make a list of elements of Ta’n tel-pilu’-nmitoq wen wskwitqamu — Different Worldviews — Piluwamsultuwakonol from videos I watch, by using an inquiry process to question and investigate differences (Activity 2)

- create a class mural showing my relationship to the environment and how it is meaningful and relevant to my life (Activity 3)

- design an individual chart showing what can be gained by exploring my environment (Activity 2)

- use a chart to analyse how senses are impacted by the environment (Activity 2)

- understand some of the cultural beliefs and values of Indigenous people in New Brunswick and how the environment has had a significant impact on these (Activity 1, 2, and 3)

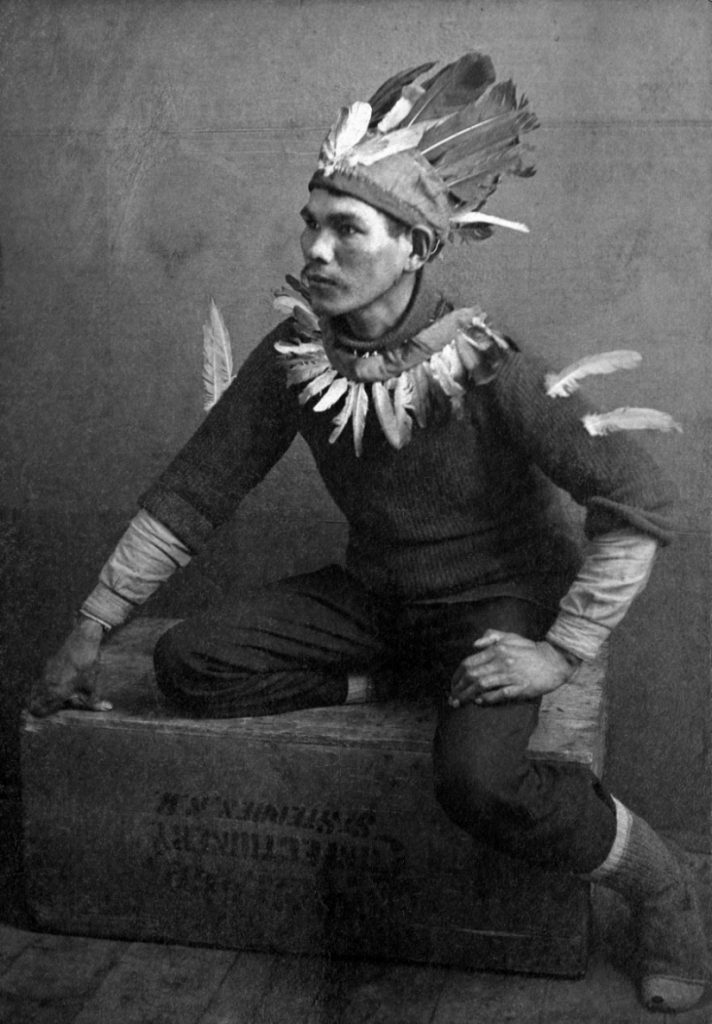

Some Indigenous people have special relationships with animals and can communicate with them. Peter Wilmot, Chief of Saqamaw (Millbrook) was one of these people:

“One day Peter went to the woods where the moose were yarding to smoke his pipe. Sitting down against a moose that was asleep, Peter lit up his pipe. As the story goes, some time later the moose woke up. ’Eh, Pieolo,’ (Oh, Peter-it’s you) he said, and then promptly went back to sleep.”

Kenny Martin and Denny Gloade, Millbrook, N.S.

This first lesson on treaty education deals with the idea of worldviews. Although the main reason to design treaties was always to establish peace at the end of each war, differing worldviews made this very difficult between Indigenous people and Europeans. For example, anchored in Indigenous belief was the view that Mother Earth is mysterious and always in flux. Another fundamental Indigenous view was that humans are equal to or are of less importance than all other creations on Mother Earth. Europeans did not think this way: for them, nature was settled, and humans were its owners. Thus, the oral traditions of First Nations people and the written traditions of the British Crown collided. Because of the differences in understanding, the treaties solved very little, and their meaning continues to be interpreted today even though they were written almost three hundred years ago. This lesson attempts to deal with how Indigenous people feel about their world and their relationship to it. It also discusses why Indigenous people believe there are benefits to both a European education and traditional ways of learning. Today, Indigenous people also acknowledge that language and cultural barriers contributed to misunderstandings during treaty negotiations. Much of the spirit and intent of treaties was lost or misrepresented.

What is a worldview? What is culture? Usually, a worldview contains a distinct set of values and beliefs that create an identity and provides a feeling of belonging to a group and a connection to one’s ancestry. A worldview gives meaning to a society and illustrates the ways in which it continues to exist.

To help students understand this, have them create a graffiti wall with principles that they live by, what they believe in, sayings or poetry that are important to them, the nature of their relationships to others. Then with a marker of the same colour circle all the things that are the same or come from the same set of ideas. Circle the ideas that are different — each with a different coloured marker. Point out that many people believe the same basic things — things that are shared in common. Discuss the ideas that seem to apply to everyone. Then point out that it is also okay to believe in things or have ideas that are different. Encourage the students to explain their own ideas that are different. Finally, explain to the class that groups throughout the world are made up of people with ideas that are often the same but can also be very different.

KMIMAJUAGNMINAL — ALL LIVING THINGS ARE RELATED — PSONAKUTOMUWAKON is one of the most complex and all-encompassing Mi’kmaw, Wolastoqey and Passamaquoddy concepts. It explains their way of life, tying together social and economic practices with systems of governance through time. It starts with the interrelatedness of life with and on the earth. Based in thousands of years of history, continuing to the present day, it is grounded in interdependence, reciprocity, and gratitude. It says as much about how something is done as it does about what is done. It is not static — there are many ways of life that would be considered part of Kmimajuagnminal or Psonakutomuwakon. It is all the ways of life and emphasizes living in such a way that respects and honours these core values and principles. These include:

- The interconnectedness of all things — land, animals, water, human beings, plants, customs, and laws;

- Change and fluidity of life and practice;

- Sustainability and cycles of life.

Thus, everything from traditional hunting to fishing to basket-making to contemporary livelihoods are a part of Kmimajuagnminal or Psonakutomuwakon. The key to understanding the concept is in how these activities are undertaken — for what purpose and with what attitude. Traditional Indigenous governance of resources has honoured the principles of interconnectedness, reciprocity, and fluidity of life that are at the heart of Kmimajuagnminal or Psonakutomuwakon. This includes how you live your life and how you think about it — your consciousness as a person. It also includes how you practice your life — the customs and codes of conduct you go by. In this lesson, the students will develop a code of conduct that shows the interrelatedness of each student with the environment.