Student Learning

I will:

- Identify the First Nations Groups which comprise the Wabanaki Confederacy and their locations (Activity 1)

- Acknowledge that there is a United Nations Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous peoples (Activity 3)

- Understand that before the arrival of Europeans, alliances were created that included trade, passage, peace and friendship, and other duties and responsibilities (Activity 3)

- Hold a debate on an issue affecting the Wabanaki Confederacy (Activity 3)

- Use a map to identify Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqewiyik communities in New Brunswick and their proximity to water forms (Activity 1)

- Understand how similar groups united to form their own conception of self- government and how they exist today (Activity 3)

- Identify Indigenous names of landforms, water forms and portages, and how the names changed over time (Activity 2)

- Ask insightful questions and offer opinions to contribute to new thinking (Activity 1, 2 and 3)

To preserve the fire, especially in winter, we would entrust it to the care of our warchief’s women, who took turns to preserve the spark, using half-rotten pine wood covered with ash. Sometimes this fire lasted up to three moons. When it lasted the span of three moons, the fire became sacred and magical to us, and we showered with a thousand praises the chief’s woman who had been the fire’s guardian during the last days of the third moon. We would all gather together and, so that no member of the families who had camped there since the autumn should be absent, we sent out young men to fetch those who were missing.

Arguimaut to the Abbé Maillard, Prince Edward Island, ca. 1740

Before the arrival of Europeans, Indigenous people had a first-hand knowledge of when and where each type of plant or animal could be found and how best to gather it for use. Many Indigenous people still do. Over many generations, they used the same spots for campsites, constructed villages, meeting points, canoe and portage routes, footpaths and cemeteries. They identified special landmarks and believed that some unusual geographical features had spiritual powers. All of this gave them a deep sense of spirituality and belonging. They did not see the areas where they travelled as land they owned themselves; it was their territory because they occupied it, sustained it and managed its resources. They were and still are an integral part of it.

Over time as people constantly moved throughout the land, they developed a collective sense of ownership. For protection from others and for sustaining the environment, they joined together to form larger groups and alliances. One of these was the Wabanaki Confederacy. Although part of the Wabanaki Confederacy, the nations of the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqewiyik and Passamaquoddy each had distinct territory and a unique language and way of life, which were different from their neighbours’. It was very difficult for them to be uprooted when the Europeans came and often wanted the same land they had.

At first, they did not exclude European settlers. However, they did not think of selling or giving them parcels of land. Only when great numbers of settlers arrived and colonial governments began to exert control did the Indigenous people realize they were losing the land itself, together with all it gave them in order to live. They were losing it permanently. So, they went to their leaders. Each nation had its own way of governing itself.

The Santé Mawio’mi

Traditionally, in the Mi’kmaq First Nation, which has communities in five provinces — Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, Québec and New Brunswick — there were seven districts (Saqamawuti) and each of these was divided among clans (wikmaq). All these districts form the Grand Council (the Santé Mawio’mi), made up of three persons: Kji-Saqamaw (Grand Chief), the ceremonial head of state, the Kji-Keptin (grand captain), who is the executive of the council, and the Putus (wisdom–keeper for the constitution and the person who remembers the treaties). The Santé Mawio’mi has supreme authority. Today, the Santé Mawio’mi continues to operate alongside the Indian Act Chiefs and Councils and the Keptin can be invited to a community of leaders such as the present-day Chief and Council. For example, the Grand Council of Santé Mawio’mi stood by the Mi’kmaq during the 2012 fishery crisis in Esgenoôpetitj (Skno’pitijk) and the salmon wars in Listiguj, Québec, across the river from Campbellton, N.B. Every year on Oct. 1st, the Grand Council Keptin speaks at the Legislature in Halifax on Treaty Day. Closely affiliated with the Catholic Church, the Santé Mawio’mi holds several large gatherings each year at Chapel Island (Potlotek Unama’kik), Cape Breton, including the Saint Anne Pilgrimage.

The Wabanaki Confederacy

The Wabanaki (People of the Dawn) Confederacy is an ancient alliance of Indigenous Nations from the Eastern Seaboard of Turtle Island. It consists of Mi’kmaq, Penuwapskewiyik (Penobscot People), Peskotomuhkatiyik (Passamaquoddy), Wolastoqewiyik (Maliseet) and Aponahkewiyik (Abenaki). This confederation covers parts of the United States and Canada and includes present-day Maine, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, parts of Québec, Newfoundland, New Hampshire, Vermont, and Massachusetts.

The Confederacy historically united five North American peoples. These were all Algonquian language-speaking peoples. As allies, Waponahkiyik (Wabanaki People) gathered periodically to exchange important information, to listen to each other’s concerns, and to resolve matters affecting their common well-being. Of vital significance were issues of war, truce, and peace. When any of the member groups were threatened or attacked by outside enemies, they could call upon each other for support. Warriors from another Nation would be rewarded with gifts. For instance, when Mi’kmaq came to the aid of their Abenaki allies at Androscoggin River, they were not only feasted, but also received precious furs.

The Confederacy played a key role in supporting the colonial rebels of the American Revolution at the Treaty of Watertown, signed in 1776 by two of the Confederacy nations, the Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqewiyik. Although the Mi’kmaw members who signed were not chiefs, the Wolastoqewiyik were. The Passamaquoddy did not sign. One of the conditions of this treaty was that the two groups would help George Washington in any future battles. Today, Waponahkiyik soldiers from Canada are still permitted to join the US military. They have done so in 21st-century conflicts in which the US has been engaged, including the Afghanistan War and the Iraq War.

The members of the Confederacy confirmed each other’s elected life-chiefs, but they did not settle on a permanent seat of government. When meetings were required, they would choose a particular village for their council fire; there, the chieftains or their ambassadors would discuss the challenges facing them and try to reach consensus on their decisions. It was not always successful. They used wampum belts to convey what had been decided. One of the most important belts represented the Wabanaki Confederacy itself, showing the political union of the four allied tribes. It displayed four white triangles on a blue background.

Having become “related” as allied nations, the chieftains or their ambassadors addressed each other as “brothers.” Allowing for some ranking difference between older and younger brothers, this represented equal status. They also used the term “father,” which they thought a fitting metaphor for someone who exercised protecting care. In contrast, the French (and English) negotiators did not understand what this meant and assumed it was real authoritarian power rather than the idea of a father. This led to serious misunderstandings during Treaty-making.

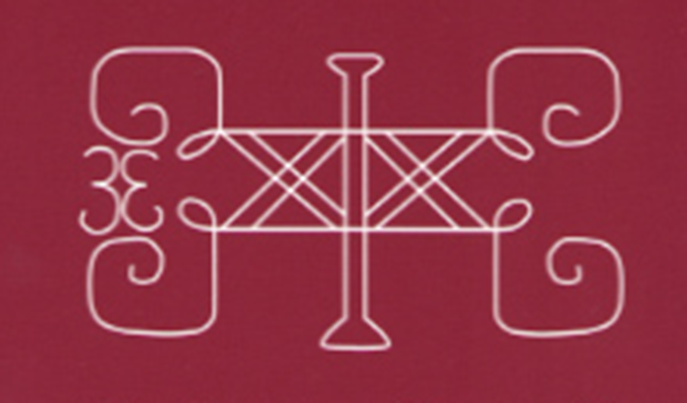

Flag of the Wabanaki Confederacy

According to Elder Jane Meader, the design of this flag is an old motif referred to as “The Gathering of Nations”. It is a depiction of a longhouse, which is where the council gathered in ceremony and to discuss and consult about governance of the nations.

The centre pole represents the core foundation of our identity as Indigenous people ― our spirituality and Creator. It is the centre and essence of all that we are. It is where all life originates and continues to exist.

The two Xs beside Creator’s centre pole represent the sacred fires of our people that burn in the longhouse. One fire represents the masculine and one represents the feminine life-forces which burn within all of us and reminds us to honour that balance and stability within ourselves and our leadership.

The four curves represent the four winds of the earth (the four directions), which carry the messages of Creator, Mother Earth, Grandmother Water, and the Spirit World.

The double curve on its side and its mirror image (left side of the flag) are there to remind us of the concept of duality that is found in many of our teachings. One of the most important ones focuses on the fact that we are both spiritual and physical beings and that what happens here in the physical world is reflected in the spirit world.

The colours of the flag are also significant. The flag features a white pattern on a red ochre background. The white represents the purity of spirit around us and within each of us, while the red ochre represents the land that these Nations have originated from and the blood of our ancestors that courses within our bodies and is embedded in the land surrounding us. Again, reinforcing the teachings of duality.

The Wabanaki Confederacy gathering was revived in 1993. The first reconstituted Confederacy conference in contemporary times was developed and proposed by Claude Aubin and Beaver Paul and hosted by the Mi’kmaq community of Listuguj (Listukuj) under the leadership of Chief Brenda Gideon Miller. The sacred Council Fire was lit again, and embers from the fire have been kept burning continually since then.

In 2015, the Wabanaki Confederacy made the following 2015 Grandmothers’ Declaration. The Declaration included mention of:

- Revitalization and maintenance of Indigenous languages

- Promoting Article 25 of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples on land, food and water:

Indigenous peoples have the right to maintain and strengthen their distinctive spiritual relationship with their traditionally owned or otherwise occupied and used lands, territories, waters and coastal seas and other resources and to uphold their responsibilities to future generations in this regard. - A commitment to “establish decolonized maps” (maps with the original names on them)

- The obligation of governments to “obtain free, prior, and informed consent” before “further infringement” of Indigenous rights

- A commitment to “strive to unite the Indigenous Peoples from coast to coast”

- Protecting food, “seeds, waters and lands, from chemical and genetic contamination”

There is no need to go through this in detail with the class. It is provided for your information. However, in Activity 3, the students will make a Charter for the Wabanaki Confederacy and discuss some of these issues.