Student Learning

I will:

- Through examination of photos and reading historical accounts, give several examples of how trading between Indigenous people and new settlers changed their lifestyle (Activity 1)

- Articulate how people placed a value on goods before the creation of a cash economy (Activity 2)

- Adjust problem-solving plans to address changing circumstances, and identify what makes good trade (Activity 2 and 3)

- Understand the reasons for warfare, diplomacy, and treaties (Activity 1)

- Research how Indigenous people and Europeans differed in their opinions about the value of Indigenous commodities and the time they took to make (Activity 2)

- Demonstrate initiative, resourcefulness and perseverance when transforming ideas into action, products and services by conducting a survey on the comparison between daily needs for items in the past and in the present (Activity 3)

- Examine political systems to understand their influence on the fact that, although treaties were established to make peace between leaders of English settlements and chiefs of Indigenous peoples, they did not include the exchange of land. (Activity 3)

This lesson focuses on some of the economic concerns that arose because of Europeans choosing to settle on land that Indigenous people used seasonally. Although the setting up of reserves is a subject treated at another grade level, it is important for the students to understand how the Indigenous lifestyle was totally changed with the arrival of permanent settlers. Indigenous life was place-based; everything was interrelated, and these relationships created responsibilities.

The Europeans came to North America with a different idea of land tenure: private land ownership under the authority of the Crown. It was customary in European societies for individual people to have title to land — including the soil and the rocks. They built permanent structures on the land; they cleared away the timber and cultivated the crops, using the same fields year after year. If a settler had title to a certain lot, he could exclude others from it. This idea was just as difficult for the Indigenous people to understand as the Indigenous way of life was for the Europeans.

With the arrival of French and English settlers and their respective militaries, relationships with Indigenous people became confused and often misunderstood. Both countries wanted the Indigenous people to serve on their military side. Initially, relationships between Indigenous people and the French settlers, called Acadians, had gone relatively smoothly. Although the Wabanaki were never consulted and no land was taken from them, Acadia was ceded to England by the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. Then the Wolastoqewiyik (about 2,000 in population at this time) and the Mi’kmaq (about 3,000) saw the founding of Halifax with its military presence as the beginning of English settlement, presenting a threat to their continued occupation of their lands. Skirmishes against the English were a result. In 1749 at Halifax, Governor Cornwallis issued his now infamous proclamation of October 1749 ordering British subjects to “annoy, destroy, take or destroy, the savage commonly called Micmacks wherever they are found”. He went further by offering a reward for every Mi’kmaw taken alive or killed “to be paid upon producing such savage taken or his scalp (as is the custom of America).” These events are sometimes referred to as the Anglo-Mi’kmaq War. It is no wonder that there have been such concerted efforts recently to have the statue of Governor Edward Cornwallis in Halifax (N.S.) removed.

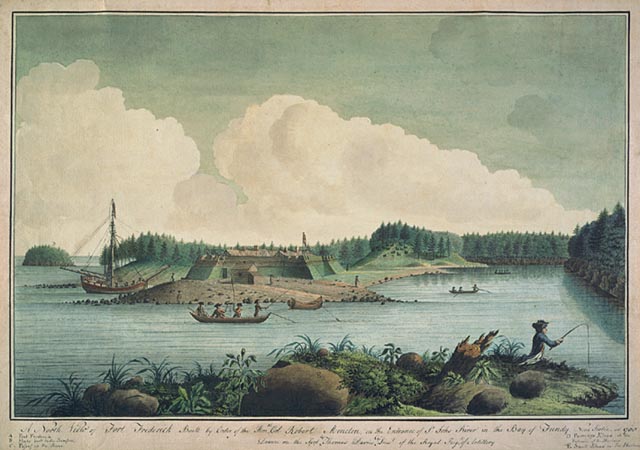

The Expulsion of the Acadians in 1755 had immediate effects on the Indigenous people in the Maritimes. Acadian farmers had provided much of their food and the French military had given them the shot and powder that they needed for hunting. The Wolastoqewiyik of present-day New Brunswick and the Passamaquoddy were the first to make peace. They sent Mitchell Neptune, Chief of the Passamaquoddy and Ballomy Glode of the Wolastoqewiyik, who arrived in Halifax in 1760. Both sides were eager to make peace as they were both facing serious difficulties. The English wanted peace so they could further settle the region. The Wolastoqewiyik wanted peace because of their dependence on European goods, so that they could re-open trade relations thanks to the fur trade. The 1760 treaty re-established the 1726 treaty. But the most important aspect of the new agreement was the creation of a commercial relationship between British merchants and Wolastoqewiyik traders. With this clause, the Wolastoqewiyik and Passamaquoddy agreed not to trade with the French. To ensure that such trade did not occur, the British agreed to establish a truck house (trading station) at Fort Frederick (Saint John). There was no surrender of land in the Treaty dated February 23, 1760. Later in 1760 and in 1761, delegations of Mi’kmaq coming from Richibucto, Shediac, Miramichi and Pokemouche as well as several Nova Scotia villages also signed the same Treaty.

(no. 6269)

Library Archives Canada/Robert Petley collection/c011203K

As the critical issue was trade relations, the Nova Scotia government (New Brunswick did not exist at this point) established government-run truck houses with set prices. Here the Wolastoqewiyik, Passamaquoddy and Mi’kmaq could exchange their furs for such items as powder and shot, axes, provisions, blankets, and clothing. Trading was extensive. For example, a truck house called Simonds, Hazen and White at the mouth of the Saint John River, over 10 years, exported forty thousand beaver skins as well as skins of muskrat, marten, otter, fox, moose, and deer.

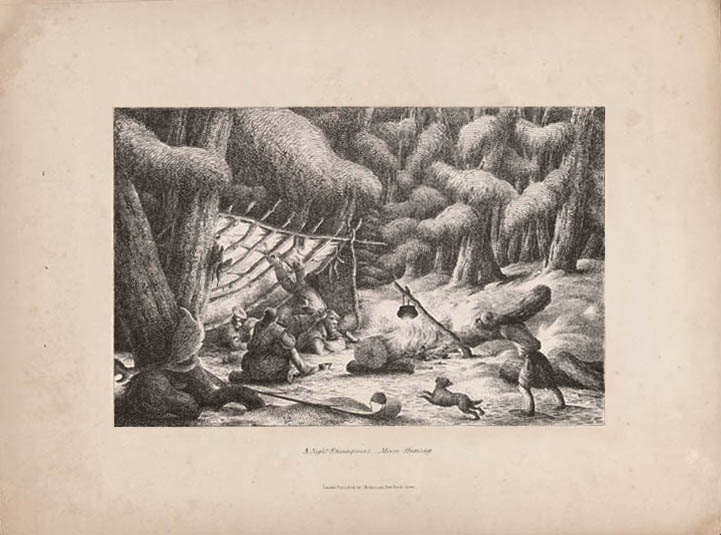

Library and Archives Canada/Robert Petley collection/e011313624