Student Learning

I will:

- Know that newcomers relied on a good relationship with Indigenous people (Activity 1, 2 and 3)

- Understand that the Crown intended to populate Waponahkik (Wabanaki Territory) lands in the Maritimes with European settlers, but did not tell Saqamaq or Kci-skicinuwok (Chiefs or Native Leaders) at the treaty conferences (Activity 1, 2 and 3)

- Weigh the impacts of the social, political, cultural, and economic systems on each other. Explain the reasons for the warfare, diplomacy, and treaties between the Indigenous people and the British Empire during the 18th century (Activity 1, 2 and 3)

- Understand that treaties were signed, and promises were made (Activity 2 and 3)

- Appreciate that treaties were Nation-to-Nation Alliances (Activity 1, 2 and 3)

- Demonstrate that treaty-making involved ritual, ceremony, commitment, and celebration (Activity 2 and 3)

- Use a collage to illustrate concepts of relationships between different peoples (Activity 3)

- Create a timeline demonstrating the Covenant Chain of Treaties (Activity 1)

- Use role play to imagine experiences of other people from other cultures (Activity 2)

Sir: After the writing, which you gave me to show my people, had been read, they decided to go to Halifax. We are therefore making ready and shall set out in two days. We are sending Francus Arseneau to get from you the letter which you promised us, which should be your assurance that the Government will grant us a domain for hunting and fishing, that neither fort nor fortress shall be built upon it, that we shall be free to come and go whenever we please. Moreover, you know what we told you, we have said the same thing in the Council; and it would be vexatious for us to undertake this journey if you do not give us some reason to hope.

Alkmou (L’kimu), Chief, Gasparau, 19 January 1755

We await this letter, which you are not to seal. When we return, we shall see you.

Indigenous people and Europeans attempted to regularize and regulate their relationship to each other through the use of written instruments — deeds and treaties. The English settlers were eager to acquire land from the Waponahkiyik. Although dealing with the same document, Waponahkiyik and Europeans saw these land transactions differently. To the Waponahkiyik, the land was a living thing, shared with the creatures on it, to be held in trust for future generations. The English, on the other hand, saw land as something to be bought and sold, like any other commodity. Consequently, from the Indigenous point of view, there was no transfer of land in any of the treaties.

Therefore, it was not surprising that both sides felt wronged by these transactions.

Covenant Chain of Treaties

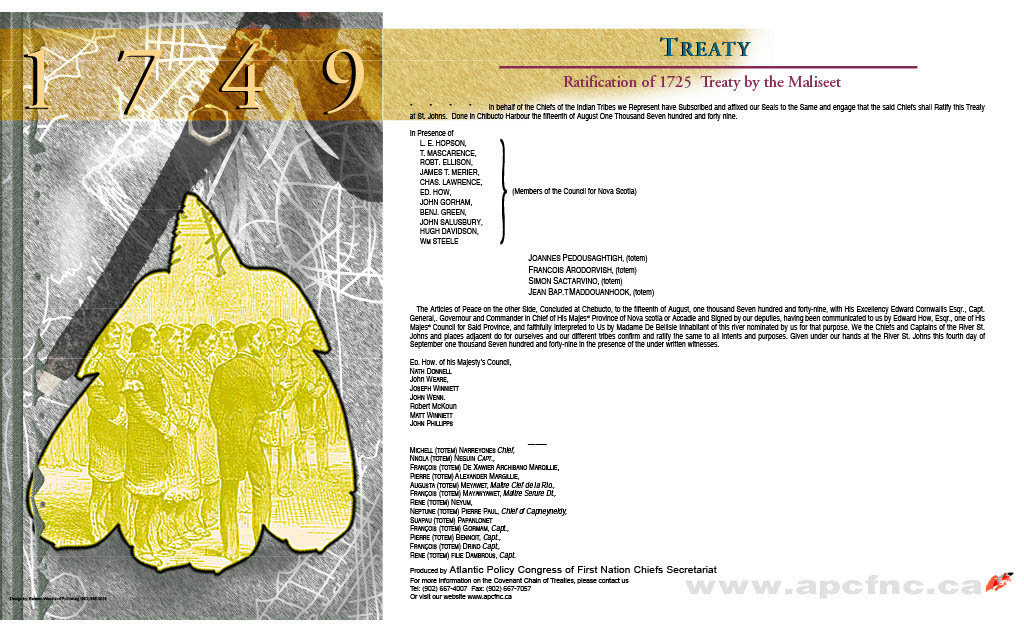

The Covenant Chain of Treaties is a group of interconnected treaties, whereby the British Crown and Waponahkiyik First Nations created a chain of related commitments to each other. There were other treaties and alliances signed before, during and after those listed here. These were selected because they figure prominently in recent cases that have been decided upon by the Supreme Court of Canada. You can find more information at the Atlantic Policy Congress website, http://www.apcfnc.ca/about-apc/treaties/.

1725/1726/1728 There were two similar treaties negotiated in Boston in 1725 by Governor Dummer. The first one was signed by four Penobscot representatives, but other groups were in attendance, including the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqewiyik and Passamaquoddy who attended the ratification. The first of these treaties, known as Governor Dummer’s Treaty, was ratified again by the Waponahkiyik, in what is now Maine. The second treaty is known as Mascarene’s Treaty since Paul Mascarene had been sent to negotiate a separate treaty for Nova Scotia. This treaty, between the British, Mi’kmaq, Wolastqewiyik (Maliseet) and Passamaquoddy was then ratified by most of the Mi’kmaw, Wolastoqey (Maliseet) and Passamaquoddy villages at Annapolis Royal in 1726 and again in 1728. It was the first of what are now known as treaties of Peace and Friendship with the British Crown in the Maritime Provinces. What is important is that this Treaty, known as Mascarene’s Treaty, consisted of two parts, one part containing Mi’kmaw, Passamaquoddy and Wolastoqey promises, and another part containing English promises, including the most important promise: to respect Indigenous hunting, fishing, and planting grounds.

1749 The Royal Commission of Inquiry into the legal rights of the Indigenous nations in North America said that: “Indians, though living amongst the King’s subjects in these countries, are a separate and distinct people from them, they are treated as such, they have a policy of their own, and they make peace and war with any nations of Indians when they think fit, without control from the English.“

1749 Treaty signed at Chebucto (Halifax) and ratified on the St. John River renewing the Treaty of 1725. Governor Edward Cornwallis, hoping to secure control over lands west of the Missaguash River (New Brunswick border), invited the two Indigenous nations to sign a new treaty to reconfirm loyalty to the Crown. However, most Mi’kmaw leaders refused to attend the 1749 peace talks in protest of the governor’s founding of Halifax that year. Increasing British military presence and settlement in the region threatened traditional Mi’kmaw villages, territories, and fishing and hunting grounds. Only the Chignecto Mi’kmaq joined the Wolastoqewiyik in signing the treaty. In the continuing campaign for Chignecto, Governor Cornwallis punished the Mi’kmaq who did not attend by offering a reward of ten guineas for the scalps of Mi’kmaw men, women and children. The London Board of Trade disagreed with this “extermination” policy.

Scrubbing the name of Halifax founder Edward Cornwallis to be put to a vote

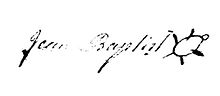

1752 The Treaty of 1752, signed by Jean Baptiste Cope, described as the Chief Sachem of the Mi’kmaq inhabiting the eastern part of Nova Scotia, and Governor Hopson of Nova Scotia, made peace and promised hunting, fishing, and trading rights. It put an end to the skirmishes of 1749-52. “It is agreed that Indians shall not be hindered from but have free liberty of hunting and fishing as usual.” It also dealt with matters of justice: for disputes between Indigenous people and the British, the English civil justice system would prevail, and Indigenous people would receive the same treatment as the British. There are many instances of the Mi’kmaq stating that they had not agreed to this term.

1760-61 Treaties of Peace and Friendship were made by the Governor of Nova Scotia with the Mi’kmaq, Wolastoqewiyik (Maliseet) and Passamaquoddy. These are the same treaties that were upheld and interpreted by the Supreme Court in the Donald Marshall Jr. case. They include the right to harvest fish, wildlife, wild fruit and berries to support a moderate livelihood for the treaty beneficiaries. While the groups promised not to bother the British in their settlements, the Indigenous groups did not cede or give up their land title and other rights.

1760 A new treaty was signed in Halifax by Mitchell Neptune (Passamaquoddy) and Ballomy Gloade (Wolastoqewiyik — Maliseet). There was no surrender of land and land was not ceded to the British. This treaty focused on renewing the old treaties of 1726 and 1749 and incorporating them into a new Peace and Friendship Treaty. The emphasis was on the trading of furs for European goods and was followed up by an agreement on trading. This Treaty was signed later in the year by delegates from Richibucto, la Hève, Schubenacadie, Pictou, Malagomich, Cape Breton, Shediac, Miramichi and Pokemouche.

1762 Triggered by Royal Instructions in 1761, Belcher’s Proclamation described the British intention to protect the just rights of the Mi’kmaq to their land “setting aside lands for Indians, incorporating the coastal areas from the Strait of Canso to the Bay of Chaleur for the special purpose of hunting, fowling, and fishing.”

Beaverbrook Art Gallery, Fredericton

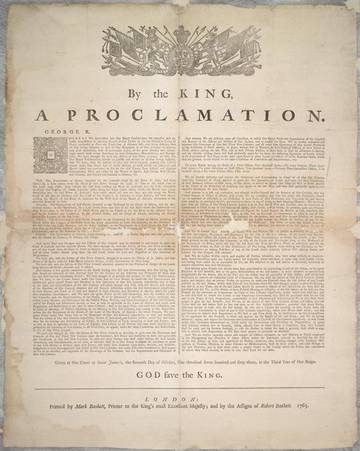

1763 The Royal Proclamation of 1763 is a complicated document that reserved large areas of land in North America as Indigenous hunting grounds and set out a process for cession and purchase of Indian lands. It is still seen as a foundational document in the relationship between First Nations peoples and the Crown. This will be further described in Grade 5.

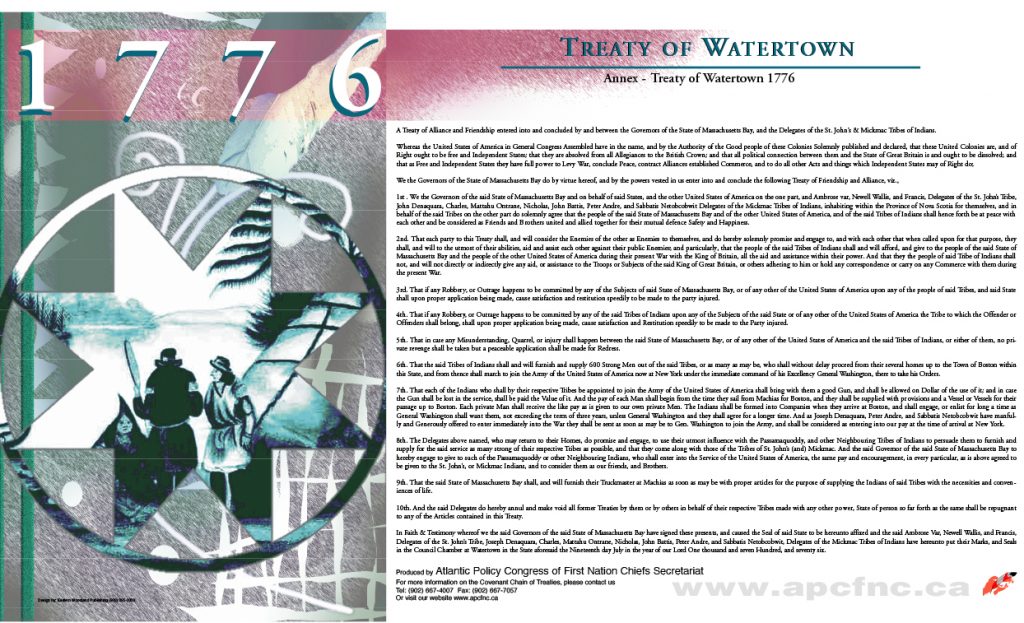

1776 The treaty of 1776, signed in Watertown, MA, USA, established relations with the newly created United States against the British. The Americans promised to approach their relationship with the Mi’kmaq in the manner of the French rather than the British.

Although there is no evidence that Indigenous people from Canada signed it, this is why Indigenous people in the Maritimes can still sign up for the United States military.

1778-1779 With the start of the American Revolution in 1775, the final treaty between the Mi’kmaq and Wolastoqiyik and the British was signed over two years. In 1778, this treaty included Wolastoqey delegates from the St. John River area and Mi’kmaw representatives from Richibucto, Miramichi and Chignecto. In 1779, the peace agreement included Mi’kmaq from Cape Tormentine to Baie de Chaleurs. They promised not to assist the Americans in the revolution and to follow their “hunting and fishing in a peaceable and quiet manner.” The military threat from the Mi’kmaq was diminished significantly by this treaty.

For Indigenous people, treaty-making operated on the principle of extended family. Treaties reflect three things: 1) interconnectedness 2) intergenerational understanding and 3) interdependency. Therefore, a treaty is considered a sacred vow or Covenant. Treaty-making is part of a sacred order and every time a treaty is made it is adding to the order. As treaties build on each other they add to and project the extended family and intergenerational life experience. As Fred Metallic, from Listuguj, says, “We are all brothers and sisters in Creation. Treaties are covenants to that order and guide us in our relationships.” (Battiste, Marie Living Treaties 2016 p. 46) The British did not at all have this emphasis on treaties being intergenerational.