Wolastoq (now the Saint John River) was, for thousands of years, the life – source for its people because it provides traditional foods and medicines. The wood, bark, and roots of nearby birch, ash, cedar and spruce trees were used for canoes, housing, tools, baskets and rope, and the riverbanks provided clay for making pottery. From the river, Wolastoqewiyik (the Maliseet) also found ready-made tools such as river rocks that were used as heating stones for ceremonies, such as the sweat lodge, and for cooking. Also, Wolastoqewiyik could mine the bedrock from which they could make tools such as axes, knives, arrow and spear tips, scrapers and carving drills. In return for what the river gave to people who lived nearby it, Wolastoqewiyik thanked Wolastoq by protecting, caring for and respecting it at all times. The interdependent relationship between people and river meant that people could live long lives depending on it. In return, the river continued to offer things back to the people without ever becoming polluted.

There was a deep connection between Wolastoqewiyik and the river. This is clear in the names of places that people gave to the river and its surrounding area. Traditional place names described the physical shape of the landscape, and, out of the river, a special way of life developed. For example, these names described locations of resources, whether the river was calm or rough and how hills or ponds nearby were used. Other names were given to show landmarks along the way and areas where ceremonies or gatherings might take place. To understand all this, people had to speak the Wolastoqey language. Today, this language is no longer well known so much of this information about the river has been lost.

Major critical changes took place in Wolastokuk (Maliseet homeland) over time. At first, a considerable amount of Wolastokuk was transformed into farmlands and development resulted in the cutting of trees to build the much-needed housing for the new settlers. The face of the landscape was drastically altered. Despite the changes, people like Gabe Acquin, an Elder, kept the language of the landscape, which, together with his knowledge of traditional Wolastoqey culture, would later influence the course of his life in colonial New Brunswick. It is as a hunter, guide, and interpreter that Gabe is best known. He was the first Wolastoqew to live at St. Mary’s year-round. He often accompanied British Officers as their guide and travelled to England several times.

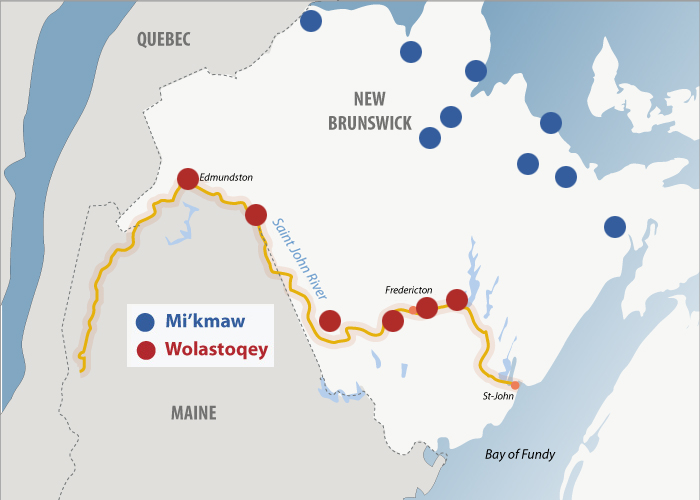

Print off copies of the map below for the students.

Read aloud ABOUT WOLASTOQ (SAINT JOHN RIVER) while students look at the photograph and trace the river (yellow) with their finger on the map below. Ask: what activities happened on this river? What communities are on or nearby this river?